Last week, we released new research on England’s unstable private rented sector. The headline finding was that well over a quarter of renters have moved at least three times in the last five years. For a family with a child that’s nigh on nomadic.

The research shows the range of serious negative consequences moving so often can have, from straining family finances to forcing children to move school.. I’ve written a full summary of it here, if you want to know more.

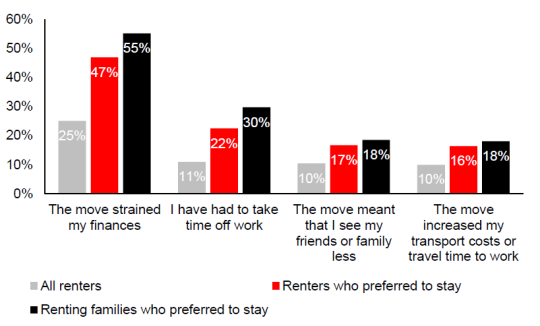

What I didn’t write about in that summary though, was the fact renters who don’t want to move, but are forced to, are much more likely to be negatively affected by the move. For example, for renting families who didn’t want to move, the number whose finances were strained by their last move rockets up from 25% to 55%.

This is very significant, because it means that giving renters more power to stay in their home for the long-term, if they want to, will disproportionately cut down the negative effects of instability. It makes the case for longer tenancies even more persuasive.

Figure 1: the extra impact of moving on renters who would have preferred to stay in their last rented home

Source: YouGov for Shelter, base: English private renters: 3530. Survey conducted between 22nd June and 13th July 2015

To understand this point properly, you need to look at the split between people who wanted to stay in their last home and those who wanted to leave.

Although some renters who wanted to move are hit by negative consequences, they are much less likely to be. Renters who wanted to stay in their home and not move were significantly more likely to be badly affected (see Figure 1). This doesn’t only apply to those whose finances were strained, it applies across a range of different effects, including those who had to take time off work, saw family less or faced extra commuting costs.

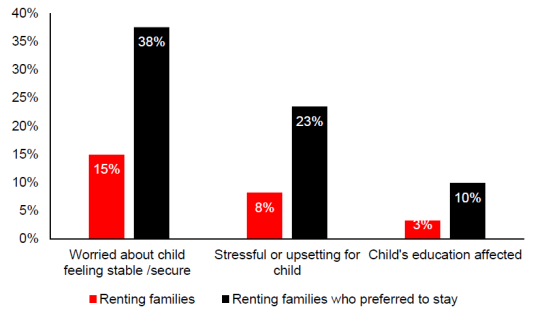

Being a renter with a child increases this multiplier effect by making you even more likely to face some negative consequences if you didn’t want to move. At the same time, these families are also much more likely to report that moving had a negative impact on their child. For example, they are three times as likely to report that the move had a negative impact on their child’s education.

Figure 2: the extra impact of moving on children of renting families who would have preferred to stay in their last rented home

Source: YouGov for Shelter, base: English private renters: 3530. Survey conducted between 22nd June and 13th July 2015

Introducing longer term tenancies wouldn’t stop people moving in the private rented sector and nor would anyone want it to. Moving can often be desirable and no renter would want to feel trapped in their home by an inflexible tenancy. But increasing the minimum period that renters are allowed to stay in their home while giving them the power to move on if they want to will deliver the best of both worlds. It will retain the flexibility of private renting that lets people move as their circumstances change. At the same time it will cut down on the worst negative effects of moving – those felt by families who want to stay.