We previously sounded the alarm that a subtle amendment to the Housing and Planning Bill allows the Secretary of State to force the sale of a much broader range of council homes than before to fund the expansion of Right to Buy to housing association tenants.

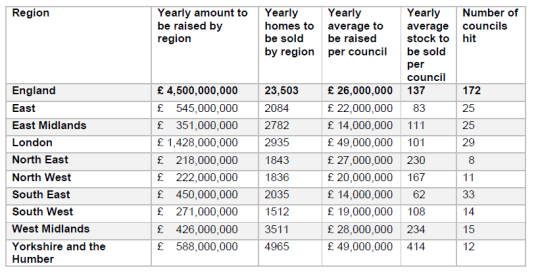

Our brand new analysis shows that to raise the estimated £4.5bn a year needed to fund the generous discounts that make Right to Buy work, the average council could be hit with an annual £26 million bill. Nationally, the forced sale policy could see us haemorrhaging 23,500 desperately needed local authority homes each year.

Shifting the goal posts

When the extension of Right to Buy was announced in the Conservative election manifesto, it was proposed that it would be funded via the sale of ‘high value’ vacant council homes. At the time, this was defined as those valued above regional thresholds.

The party estimated that £4.5bn a year could be raised in this way to fund Right to Buy discounts, create the Brownfield Regeneration Fund, pay off outstanding debts on the council homes sold and replace them, nationally, on a one-for-one (but not like-for-like) basis. They estimated all this would come from the sale of 15,000 local authority properties per year.

Previous Shelter analysis found that if the announced thresholds were applied, 3,875 homes would be sold each year. This would, however, only raise £1.4bn a year, leaving the scheme with an enormous shortfall.

Faced with this gap,it is little surprisethat a recent government amendment to the Housing and Planning Bill changed the definition of council homes liable for sale from ‘high value’ to ‘higher value’.

The Secretary of State will now have the power to demand that each local authority sell a defined proportion of their vacant homes – including homes that were not caught by the previous thresholds. The goalposts have moved considerably for councils already worried about how they will house low income families in their areas.

Show me the money

As with so many policies in the Housing Bill, exact details on how this will work are still scarce – so much so that a recent Public Accounts Committee report slammed the policy as ‘entirely speculative’.

To get a feel for the new potential impact, we’ve therefore had to make two reasonable assumptions:

- Each council contributes the same proportion of their vacant local authority stock, so the burden is spread evenly in terms of the loss of available council homes

- The same proportion of stock by size (defined by number of bedrooms) is sold off, so councils aren’t forced to sell off all their larger, typically higher value, vacant homes

Using the same method of valuing council stock as our previous analysis, we find that to reach the total £4.5bn, each council would need to sell off the top 30% of its vacant stock each year.

So if the Secretary of State is given the power to use whatever definition is necessary to raise £4.5bn per year, councils across England could face an annual bill of £26m on average. This corresponds to a total loss of 23,503 council homes each year – six times more than Shelter estimated would be sold yearly under the previous threshold regime.

Even worse, the move from flat thresholds to a relative proportion means that local authorities that thought they would escape the worst of forced sales are now amongst those facing the highest levies.

Under the threshold policy, Birmingham would have had to sell off 53 homes annually to fund a bill of around £7.3 million, placing it as the 33rd worst affected council. Following the new amendment, if £4.5bn is to be raised it could be the hardest hit area, having to raise around £145 million each year by selling off 1190 homes. Similarly, Sheffield would go from having to raise £6.4 million to £120 million each year and from having to sell just 44 homes each year to 1010.

A tax on local authority housing, with no guarantees for replacement

Crucially, councils will still not simply be asked to forward on receipts after a sale has happened. Each will be presented with a bill that they must pay based on a government formula that takes into account an estimate of the value of their vacant stock. It is then up to the council exactly how this is raised.

So if Birmingham can’t raise £145 million from sales, it may have to make difficult choices on where to get the money from. As the Public Account Committee note in their report, the DCLG “was unable to answer whether this forced sale of their assets would undermine [local authority] balance sheets”. This raises serious doubts about the government professed commitment to localism.

The lack of a pledge on like-for-like replacements means that replacement homes could be built in different areas to where they’re sold, in different sizes and different tenures. This could result in systematic replacement of genuinely affordable council housing with unaffordable Starter Homes at a time when homes that ordinary families have the means to live in are so desperately needed.

There are sensible amendments to limit the worst excesses of forced council sales and ensure the genuine replacement of affordable housing, which the Lords thankfully voted to include in the Bill but that a government majority was able to defeat in the House of Commons. Let’s hope that the House of Lords stands firm and that the government reconsiders this reckless and potentially hugely damaging policy.