Last week’s government press release on Help to Buy emphasised getting people on to the housing ladder and supporting ‘responsible lending’. Accompanying statistics, however, show it is failing to help those on normal incomes.

Supporting the credit constrained or supporting prices?

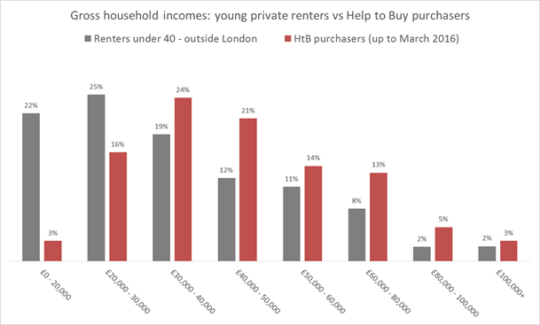

Of those using Help to Buy Equity, 1 in 5 are already homeowners and the incomes of those using the scheme are higher than those of young renters in the regions of England where it is most popular.

The median gross income of households under 40 renting outside London is £31,500 but for those who bought with Help to Buy it is £43,000– over £11,000 higher.

The government’s own evaluation acknowledges that over half of those using Help to Buy Equity could have bought something similar without it.

Buttressing a shaky system

In fact, both types of Help to Buy (the Equity Loan and Mortgage Guarantee schemes) were initially intended to support housing supply, by temporarily boosting households’ access to mortgages during the credit crunch. This was done to throw speculative developers a lifeline by keeping up demand for their products – if it’s worked at all, it’s done so by re-inflating house prices or at least preventing them falling further.

But yesterday’s figures expose the limits of using emergency measures to artificially preserve an ailing model: prices continue to be out of reach of most young private renters, even with a Help to Buy loan. Moreover, the feedback loop between housing and land means that artificially inflating the demand from home-owners to stage a short-term rescue ultimately destabilises future supply by inflating land prices.

All our eggs are in a very fragile basket

Unfortunately, it’s not just Help to Buy that seeks to boost demand for the purchase of housing. The last year has seen a perfect storm of increasing subsidies for home ownership, at the same time as cutting support for rented homes. Right to Buy figures also released last week show that only 1 in 6 council homes sold since discounts were increased in 2012 have been replaced (although this depends on which of them you think should count).

Post-Brexit, shares of major developers have slumped and storm clouds are gathering over house prices and transactions. The tax payer could see losses on the £3.59bn worth of Help to Buy Equity loans and £1.7bn Help to Buy Mortgage Guarantees, part of £42.7bn currently earmarked to support the private market.

Given the massive risk to the public purse, it’s heartening to hear calls for the ‘radical’ idea of backing away from demand subsidies and focusing on government support for low-rent homes – including from Conservative leadership candidates.

As others have argued, stretched affordability means that if developers do start to struggle, re-inflating prices will only further entrench the housing crisis. Any rescue plan must not just stem a short term slump in housing starts but reform the development system in order to break the destructive dominance of speculative building.