When our current renting laws were put together in 1988, the private rented sector looked very different from today.

The old stereotypes of the private tenant – the students who only needed a home for the uni term, or the single, childless, twenty-somethings sharing while they saved up to buy home – were closer to the truth in ’88. So it was less of a problem that the law promoted short-term renting, because many renters only needed to rent for the short-term.

Step forward to today and the picture of renters has transformed. It’s gone from a fringe tenure for those who only need a temporary place, to the mainstream for people who need a long-term home.

Renters today are more likely to be middle-aged, more likely to have kids, more likely to be in work and more likely to be on a middle income. And there are loads more of them.

But you don’t just need to take my word for it. Last week’s release of detailed data from the government’s 2014-15 English Housing Survey provides the solid evidence of the shift by comparing today’s stats with the ones from 1994-95, just a few years after the 1988 Act kicked in.

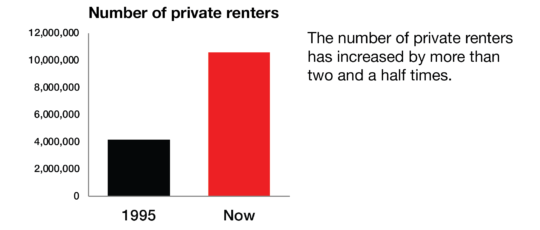

In the first place, it shows that over the last twenty years the number of private renters has ballooned from 4 million to 11 million. By implication the proportion of the population who rent has gone up from one-in-twelve to one-in-five – from fringe to mainstream.

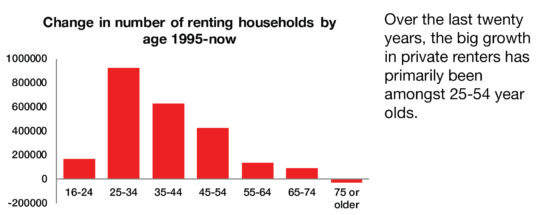

The majority of that growth has been from middle-aged households. Nearly a million 25-34 year-old households have become renters and over a million 35-54 year olds.

We know from our own research that these are exactly the people who want to be able to rent for the long-term too. For example, while an average of 56% of all renters say they think being able to stay somewhere for the long-term is very important, that rises to 73% 45-54 year old renters.

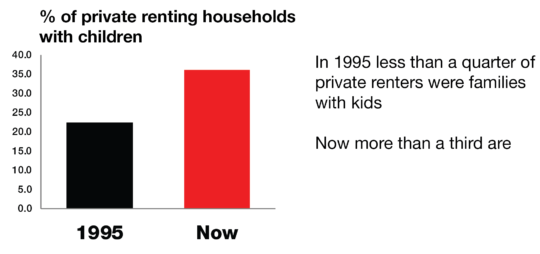

We also know that renters with children are more likely to want and need a home for the long-term as well (92% say that it’s either very or fairly important to them). As we’ve written about before and the new survey data confirms, over the last two decades the number and proportion of private tenants with dependent children has increased significantly.

Many of these families and older people would have previously been able to secure a long-term home by entering home ownership. But the dizzying growth of house prices over recent decades has closed this option down for an increasing number of people on good incomes.

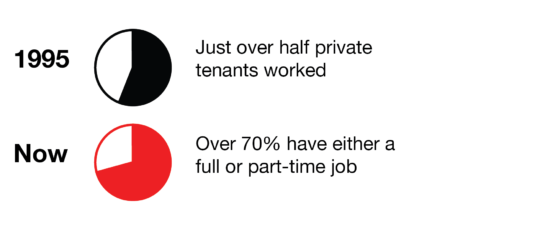

In turn, we’ve seen a growth in the number of people in employment who rent…

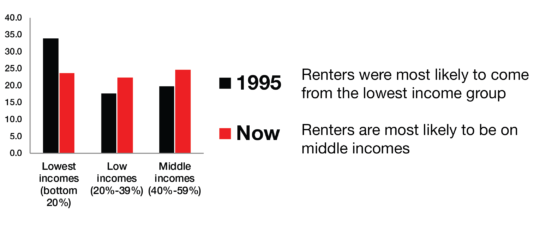

…and a corresponding increase in the number of people on middle incomes.

Twenty years ago a third of private tenants were in the lowest income quintile: now it’s less than a quarter. That’s not because renters have got richer – it’s because a growing number of people on good incomes are now priced out of home ownership.

For these middle income renters, the disappointment of not being able to buy a home is compounded by the fact that private renting doesn’t give them a secure and stable home to live in and bring up a family. They’re not only missing out on the chance of ownership, but also of control over their lives.

Some would argue that the legal renting framework that was introduced in 1988, with its short-term, minimum six month tenancies, was the right thing for the time and met the needs of many of the people who lived in it. But today it’s housing a very different group of people – and for many of them, it’s not fit for purpose.

Renters today need and want a greater degree of security and stability, so that they can be confident that – as long as they pay the rent and meet their obligations – they can stay in their home for the long-term. So that they can actually make the place they live into a home rather than just temporary digs.

This won’t happen by accident. It will only happen with legal change that gives renters longer tenancies, with the flexibility to move on if they want to. Who rents has changed – it’s time for the law to catch-up.