With party conference season on the horizon, there is a renewed chatter of a big housing ‘offer’ for young people from the Conservatives. This stems from a concern, reinvigorated by the general election, about what the decline of home ownership and rise of expensive private renting is doing to the party’s electoral fortunes.

So what are the options open to the government? So far rumours seem to be rumbling among journalists that Help to Buy – the scheme which providers consumers an equity loan to reduce the short term cost of their mortgage – may be given another push.

This being the case, we thought it worth outlining again why schemes like Help to Buy probably won’t help the government much, and explore some alternatives.

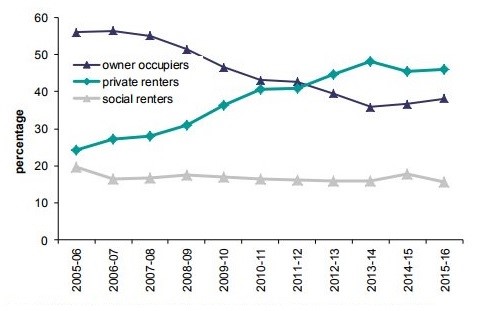

Firstly, here’s a reminder of what is scaring the Conservatives in particular:

Households aged 25-34, by tenure, 2005-2016 (source: English Housing Survey, DCLG, 2017)

Pretty stark.

If media reports are right, the government has gone on the lookout for new ways to fix this. Generally speaking, there are two priors government tends to approach a lot of policy challenges with: the Treasury would rather not spend very much more money, while Number 10 would rather not rock the boat too much – whether with backbenchers or their own base.

This, right there, is the enduring appeal of Help to Buy, and home ownership schemes generally. They don’t cost too much money (on balance sheet at least), they get the government the PR optics they want, while upsetting no one the government deems mission critical. The same logic led the last government to its ill-fated Starter Homes programme.

Perfect.

Except the very real problem is that at this point, no matter how much extra resource is thrown at them, there is no way these schemes can make a dent in the problem the government want to address. Things have simply got too bad for young people.

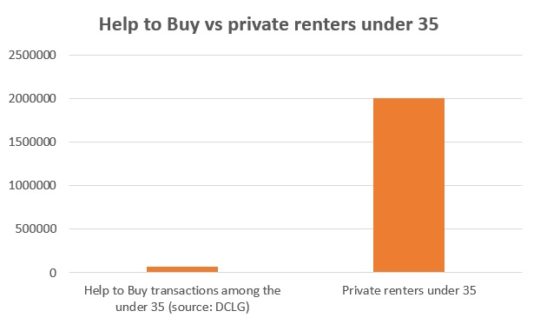

Some evidence, in case you like that kind of thing. At the last count, Help to Buy had helped about 69,000 households aged under 35. There are 2 million private rented households under 35. And by their own admission, most people using the scheme say they are well off enough to have been able to buy without the government’s help anyway. The most number of Help to Buy transactions are in the North of England, where people need less help with getting into home ownership, and the least number are in London, where people need the most help.

Which feels a bit perverse to say the least.

Help to Buy, Starter Homes, even shared ownership. Why don’t these schemes help young people at scale? The answer is fairly straight forward: because they are all linked to house prices, and house prices have risen too far beyond the reach of young people. High private rents have also sapped young private renter’s ability to save up, absorbing 40% of their salary.

The average household income for the average private renter under 35 is £25k a year (£30k for those aged 25-35), and they have very few savings.

The average household income of a Help to Buy applicant, by contrast, is £47,189 (£60k in London). You’d need an average income of £50,000 to get a Starter Home; shared ownership you need £24k, so slightly more affordable, but you still need an average deposit of £12,000 – way beyond most young people’s reach without parental help.

It’s not that much of a mystery as to why these schemes can’t solve the problem. Any solution linked to a broken market is not going to work for the vast majority of people so priced out by that market.

And of course, schemes like Help to Buy that pump more money into that broken market ultimately help drive house prices up even further, cancelling out any gains that are made.

So what are the possible alternatives? As we see it, if they want to make an impact big enough to reverse current trends, the government have basic two options.

- Fixing the market. This means reform the overall housebuilding system, so we get not only more homes but more homes people can afford, in a way that might undermine prices rather than prop them up. That requires reducing the price of land. The best way to do this is not planning deregulation but giving Development Corporations or local authorities new powers to buy up land – public and private – cheaply and ensure it’s sold to the developer with the best deal for consumers and communities, not the developer willing to pay the craziest up front price. More on this in our New Civic Housebuilding work. Encouragingly the Conservative manifesto backed key measures needed to do this, though no legislation was in the post-election Queen’s Speech.

Or

- Fund a new generation of government built affordable homes, with rents set at no more than a third of a typical low wage (a ‘living rent’). This could theoretically be combined with the Right to Buy after a certain period of time (though any discount would need to be fully funded to be sustainable), and 10 year tenancies. Unlike social housing, it could be allocated squarely at young people in work but on lower incomes, rather than just those at the sharpest end. It would give young people rents they can afford now, and so space to build up savings, with a pathway to ownership in the future. Influential Conservative campaign group Renewal called for this last year, receiving favourable write ups in The Sun among other places. Shelter is releasing our version of this idea in the near future.

Doing both would give the government a short term retail offer and a long term solution, but either would probably do the trick.

Of course, the catch is that neither is a free lunch. The first involves taking on vested interests, the second involves spending money (at least £4-5bn a year by our reckoning if you’re serious about making it genuinely affordable).

But if Conservatives, or any party in fact, wants to solve the housing problems of young people, there are no more short cuts, and it is pointless pretending there is. The scale of the political investment has to match the scale of the problem, or nothing will change.

Of course, another push on a Help-to-Buy-like scheme might allow the government to present itself as helping young people. And that may help them get through the party conference news cycle. But it will leave the fundamentals in place, along with the trends they bring about. That means an electorate in 2022 with even fewer homeowners and even more hard pressed private renters, even more pissed off about their predicament. It’s unclear they will thank government for a press release issued in the autumn of 2017.