Flat liners: housing and growth

Published: by Pete Jefferys

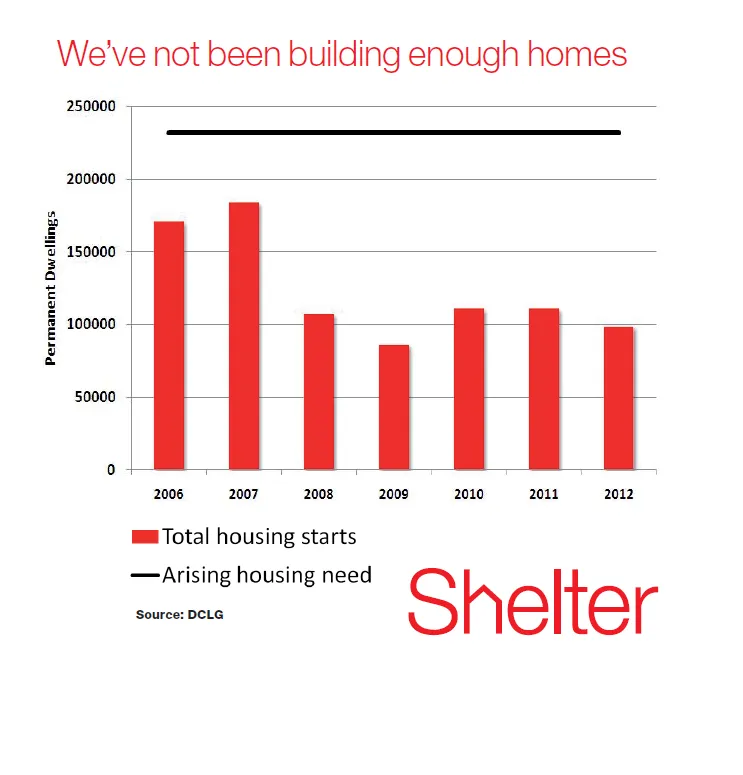

When the UK fell into double dip recession last year, we argued that we must tackle our housing crisis and economic crisis together and build homes to get us back to growth. Today, the economy is still weak with construction the major drag on recovery. We’re still not building nearly enough homes. There is a difference this year though. In the 2013 budget George Osborne announced a major intervention into the housing market called Help to Buy. It seems that the government has woken up to the idea that without a recovery in housing, wider recovery will be hard to achieve.

There is a difference this year though. In the 2013 budget George Osborne announced a major intervention into the housing market called Help to Buy. It seems that the government has woken up to the idea that without a recovery in housing, wider recovery will be hard to achieve.

So, is ‘Help to Buy’ the answer to both our housing and economic crises? Not really.

The aim of Help to Buy (as the name suggests) is a Thatcher style home_-ownership_ revolution, not a Macmillan style house building boom.

The bulk of the new policy is a ‘mortgage guarantee’ open to all buyers – not just first timers – and available on all property purchases up to the value of £600,000. The government estimates that its guarantees could support £130 billion of home loans: equivalent to a year’s worth of mortgage lending injected over just three years.

As the Office for Budget Responsibility has noted, this is more likely to lead to rising prices than new homes. But that’s the point.

The policy is a gamble on two things for the Chancellor. First, that rising house prices and a jump-started housing market will get British consumers spending again, leading to a spurt in growth and confidence from its launch in January 2014

Second, by underwriting mortgages and providing equity loans, some of Generation Rent will be able to get a foot on the property ladder. This eases the perception of a housing crisis among an important voter demographic, even if the schemes are not widely accessible to those on ordinary incomes. This can all be achieved ‘off balance sheet’, meaning that there is no impact on the deficit.

There may be some extra house building as a result of Help to Buy but it is unlikely to be a return to 2007 levels, let alone what we need to meet population growth. As Brian Green of Brickonomics has noted, there is a historic correlation between transaction levels in the market and house building. So if people start buying and selling, developers may start to invest in new stock. But it won’t be a game-changer.

So the policy is unlikely to resolve our housing shortage – but it wasn’t intended to do that. The intention is clearly to get the market moving, banks lending, people spending – and hence the economy growing.

But ramping up borrowing and house prices will at best take us back to the status quo ante: the housing fuelled consumption boom of the early 2000s. That wasn’t sustainable then because house prices had to rise faster than wages in order to release growth, meaning that houses rapidly became speculative financial assets out of the reach of ordinary families. It won’t be sustainable this time round either, because more and more families will be priced out of home ownership as the cost rises.

The government has spotted the housing element of our growth problem, but is not yet willing to face up to the real long term solution: investing in decent, affordable homes for the next generation.