Let our cities grow

Published: by Toby Lloyd

In recent years the concept of urban regeneration has fallen out of fashion, while calls to rebalance the economy away from an over-dependence on London have grown stronger. This is problematic, because it’s simply not possible to separate the drive for economic growth from the need for more and better homes. Hopefully the new commission into city growth, announced by the RSA today and chaired by Jim O’Neill of Goldman Sachs, will help to reunite these two agendas.

At Shelter, we often hear that more of a focus is needed on the housing shortage that exists outside of the capital. We couldn’t agree more: the housing shortage and the myriad problems it generates are particularly acute in the capital, but are felt every part of the county. While housing is now a top three issue of concern for Londoners, it is also a top five voter concern across England as a whole.

Nor is the story as simple as ‘overheating in London, empty homes in the North’. Every region is facing significant housing pressures: our latest research shows that house prices across England are unaffordable for working families in most major urban areas. That’s not just bad news for people struggling to get on the ladder or meet the rent – it’s damaging the whole economy. As the Centre for Cities has shown, alongside sufficient employment, the lack of attractive, affordable homes is holding back our most dynamic urban areas. So affordable homes must be central to any plan for the future growth of our regional cities.

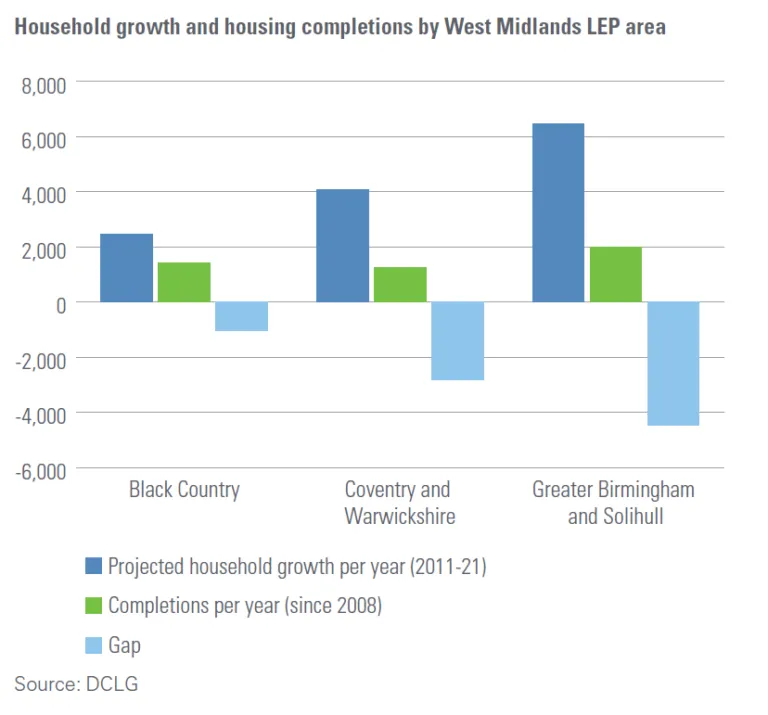

We’ve been working closely with KPMG to understand why not enough homes have been built over many years, and to develop practical solutions, by focusing on one regional housing market: the West Midlands. Not only are average house prices six times average earnings, but the annual homes deficit across the three Local Enterprise Partnership areas in the region is over 8,000.

Over several months, we’ve spoken with house builders, housing associations and local authorities to understand the dynamics of a market that should be functioning, but had failed to deliver the homes needed.

The answers we heard in the West Midlands should help inform proposals to boost our cities’ economies:

-

Focus on land on which to build homes, not just on boosting demand and the mortgage market. The way the land market in England works is strangling development and creating high risks which only the major players can survive. Without serious reform, it is unlikely the private house builder market can come close to meeting housing need.

-

Social house builders are running out of room to grow. Housing associations are forced to borrow more for each home they build under the current funding model. Without investment, they will start to hit the limits of their capacity. We need to find ways to increase investment in homes, without relying solely on public borrowing and spending.

-

City-regions need long term strategies to complement neighbourhood planning. Planning, infrastructure and housing functions could be better co-ordinated across local authorities – but this must be based on economic rather than just administrative boundaries.

We are now developing proposals that would lead to a step-change in housing supply, and contribute to city growth. As interest in the future of our urban areas grows, there is a real opportunity to develop smart, locally sensitive ways of tackling the housing shortage. And we might even rescue the concept of regeneration from terminal unhipness.