How to make your house bigger than Westminster Abbey

Published: by John Bibby

Today’s release of the April data for the Land Registry’s House Price Index contains unsurprising news for anyone who has opened a paper or turned on the TV in the last six months. House prices are continuing to rise nationally (1.5% in the last month alone).

Despite suggestions that growth in sky-high house prices in London may be slowing down, recent jumps in house prices across the country come on the back of decades of trend growth. The recent growth is not historically exceptional.

In a functioning and competitive market, we expect products to improve in quality and fall in price over time. We expect TVs, for example, to get bigger and cheaper. But the housing market in England is different: not only have house prices spiralled in the last forty years, the size of the new homes that are built in England has actually reduced.

New houses have got more expensive and smaller.

What if things happened differently, though? What if as homes got pricier you got more for your money? What if your house increased in size at the same rate as it increased in value?

Following decades of accelerated house price growth how big would the average house now be?

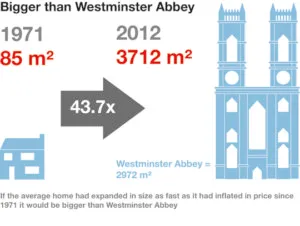

Since Shelter developed ‘the chicken stat’, 1971 has become something of a year zero for measuring house price changes, so we’ll use it as the starting point.The short answer is: bigger than Westminster Abbey, but let’s lay out the working.

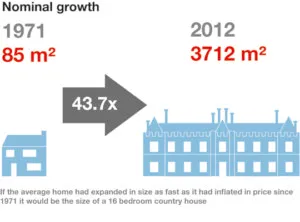

There are few statistics on the average size of houses in 1971, but as a good guide: the average size of houses included in the English House Condition Survey between 1965 and 1980 was 85 square meters. This may be the average size across a period of fifteen years from a non-mix adjusted sample, but it fits neatly with the size of a typical 1971 three bedroom semi.House prices in 2012 were 43.68 times higher than in 1971. Increasing our three bed semi by the same amount turns it into a 3712 square meter mammoth, dwarfing the 2972 square meter floor space of Westminster Abbey.For a sense of what that would mean in residential terms, it would give our enlarged semi roughly the same floor space as 16 bedroom Mamhead House in Devon.

As well as 16 bedrooms, a Mamhead-sized house also comes with 5 ‘principal reception rooms’ and 5 ‘additional reception rooms’, galleried halls, landings and corridors, a ‘main kitchen/breakfast room’ and ‘second kitchen/butler’s pantry’ (butler not included) and 8 bathrooms.

It’s arguably unfair to increase the size of our semi by nominal house prices, though. Other prices have increased since 1971, so inflating in purely nominal terms doesn’t provide a genuine illustration of how ridiculously, historically high house prices have risen.If you want to get a better impression of what a house the size of Mamhead looks like, there’s a nice walk through on the local BBC news website.

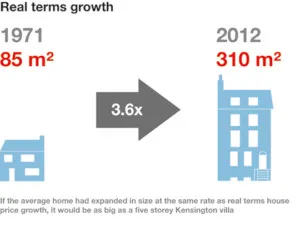

Real terms average house prices are now ‘merely’ 364% their 1971 levels (just imagine if any other basic good had increased at that rate in real terms).

If we again take our 85 square meter semi and increase it in line with this it increases to 310 square meters, roughly the size of this five storey Kensington villa. As well as 5 bedrooms our Kensington pad boasts an entrance hall, drawing room, kitchen/family room, dining area, study, two bathrooms, shower room, cloakroom and utility room.

It’s no Mamhead House, but a semi that grew in real terms would still be very big.

It’s no Mamhead House, but a semi that grew in real terms would still be very big.

The real world doesn’t work like that, though. In reality, spiralling house prices have not improved the quality of the homes that we build or the number of homes that are built. We now build some of the smallest (as well as the most expensive) homes in Europe and even then, we don’t build nearly enough of them.

At the beginning of May Shelter and KPMG set out how the next government can build enough homes to stop decades of house price inflation and stabilise house prices so that things begin to improve. Now we need the political parties to pledge to put it into action.