Nostalgia for the 1930s

Published: by Toby Lloyd

The BBC ran an interesting documentary on house building a few weeks back, which you can watch here. As it was a prime time discussion of why we don’t build enough homes I hardly want to complain – but there was an element of received wisdom to it which did annoy me slightly.

While it did explain the central problem of land in house building (and how land is different to other commodities) and why the volume builders’ model will struggle to ever meet housing need – it fell into the common trap of idolising one bit of the past: the 1930s.

The programme told us that in that decade small private builders were free from all planning restrictions to build high quality, spacious family homes for everyone. It was a time when the middle classes were unshackled from rented housing to own their homes. It was freedom personified and everyone loved it.

Of course, many commentators idolise the house building programmes of late 1940s or 1950s, depending on their political allegiance. But the 30s seems to be the connoisseur’s golden age, a period which can safely be eulogised without fear of contradiction. No doubt this is partly because the 30’s were longer ago, and on the other side of the great psychic rupture of the second world war: few people now have any direct knowledge of the time, and even ‘historical series’ data sets tend to start after 1945. I suspect the decade of the National Government also appeals because – despite the intense political controversies of the time – it is not claimed by either left or right as part of their political identity.

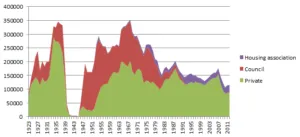

There is much to look back on with envy. The 1930s was the undisputed high water mark of housebuilding, with private firms alone building over 250,000 homes per year in England. By 1939, one in three households lived in a home less than 21 years old.

(Tom Chance’s graph, combining two not-entirely comparable sources: like I said, the data sets break with the war)

So why do I reach for my revolver when I hear the 1930s eulogised? The problem is two-fold. Firstly, there are often some lazy assumptions about what was really going on then. It’s true that the private sector built far more than it does today, and that the national planning system had not been created. But that doesn’t make the 1930s a free market paradise. There was planning – it was just rather patchy and inconsistent. And the public sector played a huge role, building more than 50,000 homes a year. In fact, it was public investment in new council housing following Lloyd George’s ‘homes fit for heroes’ campaign after WW1 and Addison’s Housing Act 1919 that kick started the interwar construction boom, and then sustained it.

And as Brian Greene points out, market conditions were radically different then: there was a huge amount of capital saved up in building societies while international capital movements were heavily restricted. Millions of people who had grown up in private rented homes, often a family to a room, were keen to use that cash to buy a home for the first time – and there was little or no chance international investment money would beat them to it. As a result, single-earner families could buy a family home with a mortgage of three times an ordinary worker’s salary. This is not a situation you can readily compare to today, to put it mildly.

Secondly, yearning for the 1930s ignores how utterly unrepeatable they were. London, Birmingham and many other cities more than doubled their footprint in that decade. Much of the growth was in low density suburbs enabled by the rise of the automobile, and which now present a serious challenge to economic and environmental sustainability. It was precisely in reaction to this sprawling of our cities that the 1947 planning system was created. That bête noir of frustrated liberalisers today – the Green Belt – was designed to prevent our cities doubling or tripling every decade, for the good of the cities themselves as much as to preserve the countryside.

The lesson I want us to learn from the 1930s is that we can build far more homes than we do now, by supporting a mixed economy of public and private investment. But we can’t do so by simply spreading our cities out in every direction and expecting everyone to drive great distances to get anywhere. We learned the importance of intelligent planning from the 1930s. Let’s not forget it now.