Let’s all blame planning

Published: by Pete Jefferys

We know we don’t build nearly enough new homes in England, but why is that? One commonly made argument is that it is primarily the fault of the state, which controls and limits the use of the most important raw material in house building: land.

This is how the argument often goes. The house building industry would be able to build the homes we need if only there were a true free market in land use. In other words, if we removed or reduced some of the controls of land use by the state (green belts, Local Plans) then the industry would respond efficiently and build more homes. Often the 1930s is pointed to in this argument – the decade when private house-building boomed and many of London’s suburbs were built, doubling London’s geographic footprint.

I don’t agree that blaming planning is the best route to building more homes. What are my arguments?

1. We don’t have a 1930s building industry

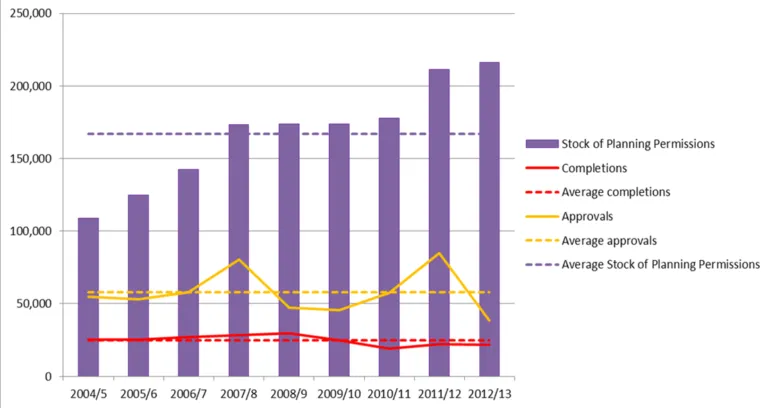

I came across this excellent graph from Jamie Ratcliffe at the Greater London Authority (below). It shows that the stock of plots with planning permission has been rising over the last decade, but the industry has not responded with higher levels of home building. In effect, there is lots of developable land in a very high demand area, but that is not translating into more homes.

London: Planning Permissions, Completions

In part, I would argue that this is because the industry is very different to the one that existed in the 1930s. Then a lot of house building was commissioned by local authorities for use as council housing. This can be built at a much faster rate because homes can be almost instantly occupied so long as there’s a waiting list.

Homes for sale can only be built and sold at a rate which maximises the price at which they are sold (i.e. very slowly). This is because the developer has paid for the land on the basis of selling homes at the maximum price. Once locked into the land price, they have no choice but to build slowly if they are to turn a profit.

This is why building collapsed in the wake of the recession. As people were no longer able to borrow massive mortgages, they could no longer buy homes at the prices builders had anticipated when they bought the land. Builders said that this made the sites “unviable” and argued that the answer was to cut back on affordable housing requirements, reducing their costs.

In London, the stock of land with planning permission is also a hugely valuable global commodity. According to a 2012 study, nearly half of all land with residential planning permission in London was owned by non-builders. Land with permission is held and traded as an asset in its own right, it doesn’t necessarily quickly become homes.

It’s simply not true that planning is the sole barrier to building homes. Land ownership and the type of house building industry we have matter too.

2. Planning is political

Of course you might argue that if we had a massive shake up to planning – such as taking away green belts or scrapping local planning committees – then the industry would be forced to adapt.

The huge legacy developers would be swept away as their creditors realised that the land they owned was no longer worth what they paid for it and forced them into insolvency. New developers would emerge based on a high rate of house building at low margins on former green belt land. London’s footprint would double again in under a decade as a new wave of low density suburbs were built.

However, I would argue this is not a plausible scenario for one simple reason: planning is and will always be political. Land is naturally scarce therefore we have a planning system, not the other way around.

The reason no politician will call for greenbelts to be scrapped is that politicians are elected and most people don’t want their local greenbelt to be scrapped. It might sound obvious, but it’s a point that those who blame planning always fail to address. The fundamental problem is convincing people that building homes near our successful cities is something that will benefit them, their family and their community. We need to get people to want new high quality local homes, jobs and services, and to see that the way to get them is through allowing local development. We won’t do that by forcing communities to accept unaffordable tiny flats by liberalising the planning system.

3. Why not just a bit of planning liberalisation then?

There will be some who are now thinking, isn’t the political impossibility of scrapping greenbelts a straw man? Surely we just need a bit more liberalisation to get homes built, not a wholesale change?

Well I’d refer you back to point 1 above. If we just took away green belt designation from some greenbelt land around our big cities, then it would be rapidly bought, owned and controlled by the major developers – and speculators planning to sell on to the major developers. They would then build it out as slowly as required by the land price they paid. Just look at the graph from London! You can increase the amount of land with planning permission, but it won’t necessarily increase house building.

These are the horns of the dilemma: massive planning reform might get more homes built, but it’s politically unrealistic. Medium planning reform is politically realistic but won’t change the nature of the industry and therefore won’t radically increase house building.

So what do we need?

We need to move the debate about building more homes on and face up to the fact that it’s not all the fault of planning. That view fails to address the fundamental problem that planning is political because what local people think matters. It also fails to address the problem that we have a development industry that has grown up around dysfunctional land markets and is dependent on a model of selling slowly to maximise prices.

Instead, we need to look at other models and take inspiration. In Northern Europe they build beautiful and affordable suburbs, which enhance local communities and increase the capacity of local infrastructure and services, not add to the demand for it. And yes, they do this in areas with higher population densities than England.

Germany and Holland’s success is from pro-active planning, not less planning. Private developers and city authorities work together to bring in land at a low cost and get high quality homes built quickly in all tenures. Building more homes can be something that local politicians make their careers arguing for, because they know it will bring additional services, revenues and affordable homes.

Doing this kind of development – including on the least attractive greenbelt land near transport hubs – is a much more attractive model than full-scale deregulation of the greenbelt. The politics is still hard, but I believe possible if done sensitively and clearly for the benefit of the local community.

We can build the homes we need, but only if we move on from the tired old trope that planning is the problem.