A step too far in the slow assault on social housing?

Published: by Toby Lloyd

Something truly extraordinary happened the other day. A coalition of over 200 landowners and property companies in Westminster protested that the government is undermining the economic health of London, by letting its own members avoid commitments to build much needed affordable housing. These commitments – known as Section 106 Agreements, or just S106 – are deals done between developers and councils, in which the developer agrees to provide something for the community in exchange for getting planning permission. Although S106 deals can require contributions to schools, transport or other community facilities, most often it’s affordable housing. In fact, S106 is one of the main ways affordable homes are paid for – especially since the amount of grant available has been cut.

As developers normally – and correctly – complain that such obligations reduce the profitability of their businesses, this move sounds like turkeys voting for Christmas. I’ll come on to why I think they’re taking this courageous position later, but for me the most important point is that this incident shows just how far the government has gone in weakening the supply of affordable housing: even those who stand to profit think this is a step too far.

At no point has any minister stood up and announced their determination to abolish social housing. In fact, they’ve been proud to claim that they have turned around the long decline in affordable housing provision.

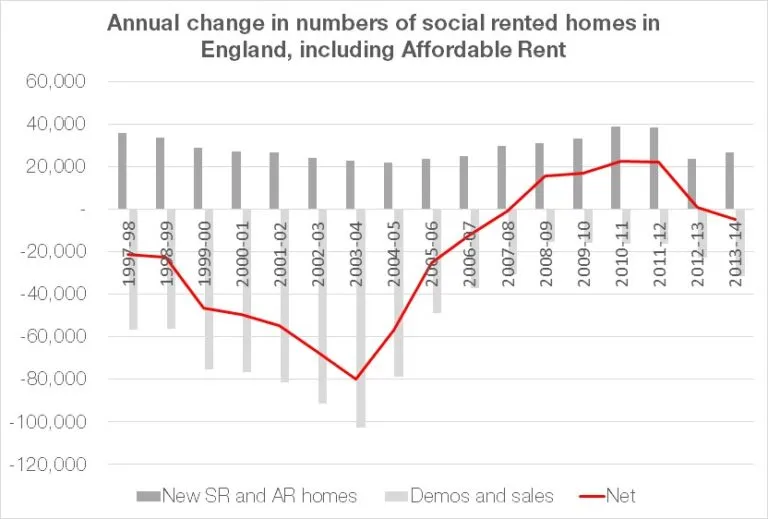

The sharp-eyed will see what I did there, which is just what all recent governments have been doing: blurring the distinction between social and affordable homes, and between new building and the total stock. These are important but rather technical distinctions, which we’ve discussed elsewhere: the short version is that since the 1980s the total stock of really affordable, secure social housing has been falling. The last Labour government continued the trend of running down the social stock, and only belatedly increased social home building following the financial crisis. Since then, building the new type of less affordable, less secure homes has partly, but not fully, made up the difference.

Source: DCLG Live tables 678, 684, 1009

These finer points are easily glossed over in well-crafted press releases, so the casual observer could be forgiven for thinking this government wanted more social housing, not less.

But the evidence of government action, as opposed to rhetoric, is unmistakeable. Here’s a very quick summary:

- 2010 Emergency Budget – cut the affordable homes budget by 60%.

- 2011 Affordable Rent regime ends funding for social rented housing in favour of a new tenure at up to 80% of market rents, and forces social landlords to convert existing homes to the new model wherever possible.

- 2012 Right to Buy discounts increased to boost sales – while the promise to replace all homes lost has not been fully delivered, and in any case replaces social rented homes with the new Affordable Rents.

- 2013 Growth & Infrastructure Act allows developers to reduce affordable housing provision under S106 agreements

- 2013 New rules allowing conversion of industrial and commercial property to residential prevent Councils requiring affordable homes under S106 agreements

- 2014 Chancellor announces new Housing Zones – but the Local Development Orders mechanism excludes S106 obligations

- 2014 The Prime Minister launches an innovative Starter Homes scheme that unfortunately… precludes S106 obligations

- You get the picture…

This latest move is very much in keeping with the trend: a small change to planning rules, snuck out in a ministerial written statement, and presented as a positive step to remove red tape, tackle empty homes, and get more homes built. Who could argue with that?

The problem is that by allowing developers to subtract the value of any “vacant” buildings from the total they are required to pay in S106, this hugely reduces the amount of S106 contributions that developers have to make. It also incentivises them to show that as many buildings as possible on a redevelopment are “vacant” – which of course they must be before they can be knocked down and replaced. This could have big implications for estate regeneration projects, many of which are already failing to replace the social housing lost.

So why is the Westminster Property Association opposing this fillip to its members’ profit margins? Its statement cites the economic importance of affordable housing and commercial property in central London, an important point that doesn’t get heard enough. Thriving cities need homes for people on a wider variety of incomes, or they risk strangling their own economic and social life.

My guess is that the development industry is also mindful that removing affordable housing obligations ultimately benefits landowners, not the actual developers – because developers simply end up paying more for the land.

But most importantly, developers know that they operate in a democratic political context. Without public consent in the form of planning permission they cannot do business, and that consent relies on development making a real contribution to local places and local communities. When the government offers developers the chance to increase profits by giving less back to the community, it must be very tempting – and most of the time they are understandably glad to accept. Perhaps they think that this time the government’s steady, creeping assault on affordable housing has finally overstepped the line.