Time for the Bank of England to join the macroprudential party

Published: by Adam van Lohuizen

Last month the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) announced new measures to limit lending to investors. If you’re wondering what New Zealand has to do with the housing crisis in England, keep reading and it will become clear…

Here are some snippets from the statement by the RBNZ.

New Zealand’s financial system is sound and operating effectively, but faces significant risks, Reserve Bank Governor, Graeme Wheeler, said today when releasing the Bank’s May Financial Stability Report.

“Auckland’s median house price is 60 percent above its 2008 level, and house prices in Auckland have been rising rapidly since late last year. This reflects ongoing supply constraints and increased demand. Prices in the Auckland region have become very stretched, increasing the risk of financial instability from a sharp correction in prices.

In response to the growing housing market risk in Auckland, the Reserve Bank is today announcing proposed changes to the loan-to-value ratio (LVR) policy. The policy changes, proposed to take effect from 1 October, will:

Require residential property investors in the Auckland Council area using bank loans to have a deposit of at least 30 percent.

Increase the existing speed limit for high LVR borrowing outside of Auckland from 10 to 15 percent, to reflect the more subdued housing market conditions outside of Auckland.

“We are proposing these adjustments to the LVR policy to more directly target investor activity in the Auckland region, where house prices relative to incomes and rent are far more elevated than elsewhere in New Zealand.

“The objective of this policy is to promote financial stability by reducing the rate of increase in Auckland house prices, and to improve the resilience of the banking system to a potential downturn in the Auckland housing market.”

Mr Wheeler emphasised that while the new measures aim to moderate housing demand, policies to ease housing supply constraints in Auckland remain the key to addressing the region’s housing imbalances over the longer term.

“Given the importance of encouraging residential construction activity in Auckland, and consistent with the existing LVR policy, the proposed LVR restrictions will not apply to loans to construct new houses or apartments.

Now, if you replaced the terms New Zealand with United Kingdom, Auckland with London, and Graeme Wheeler with Mark Carney, and you would think you were talking the situation here in England.

These measures are known as macroprudential regulation, which I’ve blogged about before. New Zealand isn’t the only country to adopt this type of regulation to prevent too much loose mortgage lending from driving up house prices unsustainably. Closer to home, the Central Bank of Ireland announced very similar lending limits in January.

What is particularly interesting about the RBNZ model is the way in which the ‘speed limits’ are targeted at specific sections of the market by:

- requiring buy-to-let (BTL) investors to have higher deposits than owner occupiers, it helps level the playing field between ordinary home buyers and landlords;

- setting higher LVR limits for Auckland it addresses regional imbalances in the property market; and

- excluding mortgages for new homes, it creates an incentive for investment in the supply of new housing.

The combined effect of this targeting strategy should help to address the fundamental problems driving high house prices, at the same time as slowing demand side pressures on the housing market.

Housing market conditions appear similar in both countries – so what is the Bank of England doing compared to its counterparts in New Zealand? The Bank has taken some small steps in the right direction including:

- a new affordability test to ensure that households can pay their mortgage if interest rates rise;

- new powers to set LVR limits for owner occupier mortgages; and

- a 3% leverage ratio on banks and building societies.

But the effect of these steps has been minimal. Many banks were already operating within the 3% leverage ratio – so this has had little impact. The LVR powers are yet to be used, and if they are implemented they won’t apply to BTL mortgages, but only to owner-occupiers. This is the opposite of the New Zealand strategy – for which BTL mortgages are the target – so it is odd that they are not within the Bank of England’s powers.

To the Bank’s credit, it did ask for power over BTL mortgages as well, but the government is yet to grant them power to regulate them. It will consider this in the new Parliament.

The Bank’s Chief Economist has described macroprudential regulation as the “new kid on the block and perhaps even the next big thing”. But so far the Bank of England has been sitting on the side lines, as house prices continue to rise to astronomical levels.

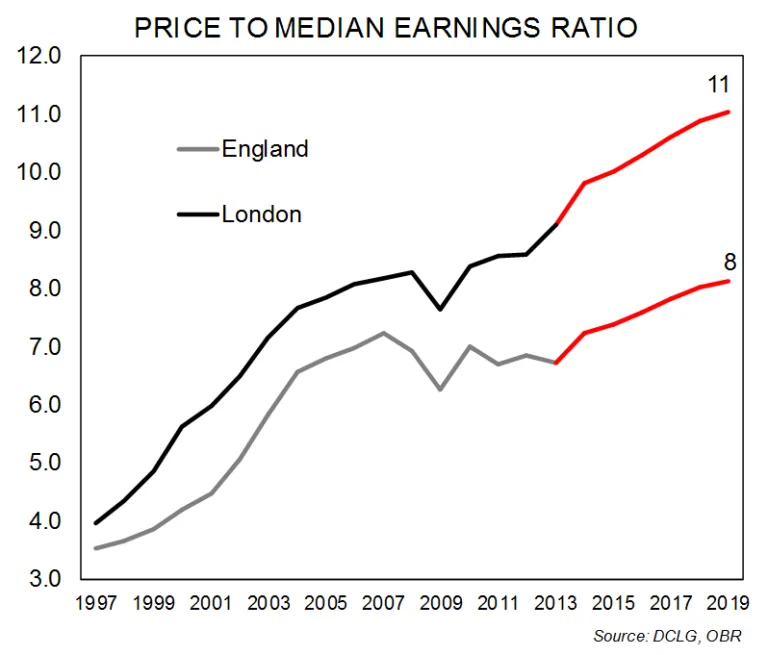

London house prices are set to reach eleven times income by the end of the decade, compared to just four times in 1997. While BTL lending in the March quarter this year made up the highest proportion of total lending since mid-2006 when quarterly records began.

How much worse does it have to get before the Bank of England steps in? That is a question only the Bank itself can answer. Hopefully it will be sooner rather than later.