A meaningful definition of child poverty must focus on the cost of housing

Published: by Shelter

Last week the government confirmed that it will change the way we measure the number of children living in poverty in the UK. The Secretary of State for Work and Pensions, Iain Duncan Smith, stated that “it is not enough to tackle the symptoms without also tackling the underlying causes”, and that the new measures would “reflect our (the Conservative Government’s) conviction that work is the best route out of poverty”.

Under the most widely used current definition – brought in under the last Labour government, and supported by David Cameron’s Conservatives at the time – a child is considered to be living in poverty if the total household income is less than 60% of the median income nationally (adjusted for household size). This includes both households in and out of work.

The government’s proposed definition abandons measuring poverty in terms of relative financial disadvantage – in other words, how much money a household has to feed, clothe and provide shelter for itself. Instead, the government will introduce a statutory duty to report on behavioural factors, such as worklessness, family breakdown, GCSE attainment, and other factors designed “to measure progress against the root causes of poverty”.

Understandably, the rhetoric surrounding the new definition could cynically be analysed as the Conservatives ‘rolling the pitch’, ahead of potential cuts to working tax credits and housing benefit, due to be confirmed in this week’s emergency budget. Regardless of the motives, there are fundamental problems with both the current and proposed definitions of child poverty.

A key point is that under the current definition over two thirds of children in poverty live in households where at least one adult works, significantly undermining the government’s new definition: while existing measures have exposed the growing problem of working poverty, these families would cease to be a problem under the new measure. This is helpful if you want to maintain that work is the key route out of poverty, but disingenuous if you care about the material circumstances of children.

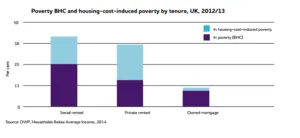

And this is before the most fundamental flaw in headline child poverty definitions, the omission of housing costs[1], is taken into consideration. In other words, when we look at household income after renting and mortgage costs have been deducted, we can observe that a significantly higher number of households fall below the poverty line. Stats from the DWP, shows that roughly 15 per cent of the population are living in poverty under the current definition. This rises to 21 per cent once housing costs are factored in, meaning that 3.7 million households are living in housing induced poverty.

The type of tenure you live in is a significant determinant of whether you live in housing induced poverty, and the impact is felt most acutely by renters. The graph below (produced by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation) shows that ‘housing induced poverty’ is much higher for renters, especially for those living in the private rented sector.

Furthermore, some parts of the country are clearly more affected than others. At one extreme, once housing costs are considered the number Londoners living in poverty almost doubles, from just over 1 million households, to just over 2 million.

Of course, all of us are faced with paying for housing costs (which includes things like water costs as well as rent or mortgage). But while the average home owner has benefitted from low mortgage rates (and is increasingly likely to have paid off their mortgage), renters are struggling with costs that continue to rise every year. As the IFS points out, average mortgage holders have reduced the proportion of their income spent on housing costs from 18% to 13% between 2007-08 and 2012-13, which drove a real terms fall in the average housing costs for all households. In contrast renters, who have also become more numerous, have seen the proportion of their income spent on housing costs increase from 26% to 28% over the same period. Moreover, falls in housing costs have been far more muted for low income households.

This is felt more acutely by households because of stagnant wage growth, now compounded by recent freezes to housing benefit for private renters. The graph below highlights the extent to which rent increases are outstripping wage increases.

All of this is lost in the rhetoric surrounding the new definition; which points to behaviour being the cause of poverty, with poverty itself being a symptom of unemployment, family breakdown etc. Not only does this viewpoint fail to explain working households who are below the poverty line, it ignores key evidence that highlights the detrimental impacts that low income and unaffordable rents have on employment prospects, education, health and the wellbeing of the family unit. In sum, such issues can be viewed as the symptoms of poverty, not the causes – contrary to the view of Iain Duncan Smith.

The government’s proposal to reframe the child poverty debate by linking definitions to behaviour attitudes (such as worklessness and family breakdown) wrongly casts all vulnerable, low income households as the agents of their own poverty. We need a constructive debate about the extent of poverty in the UK and how we can set targets and develop policies to reduce the numbers affected by it. To do this we will need a clear focus on the structural and financial causes of poverty, with the impact of rising housing costs front and centre – as well as supporting families and addressing barriers to work and progression. But if we’re moving to a multidimensional measure, it would be a missed opportunity not to capture the importance of overcrowding, poor conditions, stability and security on the development of families.

[1] Housing costs include rent, water rates, mortgage interest payments, buildings insurance payments and ground rent and service charges