The number of homeless households in B&B is on the rise again

Published: by Shelter

The latest government statistics show that the use of Bed and Breakfast (B&B) to accommodate homeless families with children is making an unwanted comeback. Over the last 5 years the number of households accommodated in B&B has more than doubled, from 2,050 to 5,270. The rise in B&B use is even more acute in London, where the number of households has more than tripled. One inner-London borough has reported a 1500% increase in B&B use over a two year period alone. And B&B reflects an overall increase in the use of temporary accommodation (TA). The number of homeless households in TA has increased by 26% over the last 5 years, from 51,350 households in 2010 to 64,710 in 2015.

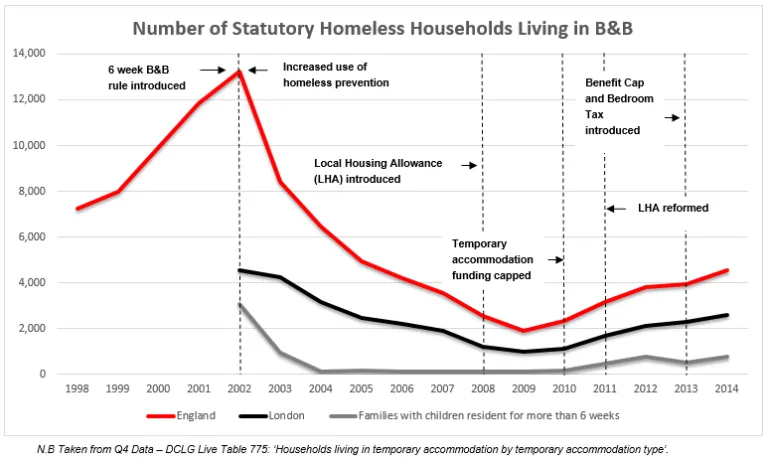

The figures are disheartening. As the graph below shows, prior to 2010 there had been a 7 year decline in councils using B&B, triggered by the introduction of the 6 week limit and a greater emphasis on homeless prevention, which reduced demand for TA. As a result, the number of families staying in B&B for longer than 6 weeks was small from 2004-2009, but has since started to increase.

Councils in England have a duty to provide TA to homeless households who are ‘unintentionally homeless’ and in ‘priority need’ (certain vulnerable singles and couples, and families with children,) until an offer of ‘settled’ private or social sector housing can be made.

While councils try to place homeless households in self-contained flats and houses, with exclusive use of facilities, they are finding it increasingly difficult to procure this type of accommodation. When self-contained isn’t available, councils rely on other forms of TA, notably B&B, where the kitchen and toilet can be shared by eight, nine or ten strangers, and often a whole family eats, lives and sleeps in just one room. This has detrimental impacts on the education, health and wellbeing of families, as well as on the employment prospects of adults.

So why are councils having to rely on B&B again, especially in London? The challenge comes in three ways.

Firstly, TA use in general is being fuelled by an increase in homelessness, in particular in areas where rent levels are way above the amount of housing benefit a households can receive. Essentially, demand for emergency housing is growing quicker than the rate at which councils can procure self-contained TA, and often B&B is the only offer that can be made to a household that approaches as homeless.

Secondly, the supply of self-contained private and social sector housing (which in the past formed a sufficient supply for TA) is drying up due to a combination of general high demand and landlord’s being able to get a better deal elsewhere than what councils can offer. With such a small pool of supply to hand, councils often face a difficult choice: accommodate homeless households in B&B, and for longer periods of time; or place households further away, in more affordable parts of the country, but where employment options are limited and support networks yet to be established.

Thirdly, while demand for TA is growing, the number of households leaving to be accommodated in ‘settled’ accommodation has remained static. Options in the social rented sector have narrowed due to a combination of Right to Buy, a shortage of new affordable homes and the impact of welfare reforms, which have forced housing associations to set strict affordability tests before accepting homeless households.

Meanwhile, since 2012 councils have been able to rehouse a homeless households in the private rented sector without the household’s consent. This was controversial, given that it increased the risk of repeat homelessness. But it should in theory have increased councils’ options. However this has been undermined from the onset, and increasingly so, due to reforms to housing benefit. The Government’s proposed 4 year freeze to Local Housing Allowance (housing benefit in the private rented sector) combined with the lower benefit cap will make finding settled accommodation in the private rented sector for homeless households an almost impossible task across much of the country.

In the current housing climate temporary accommodation provides vital support for households who find themselves homeless. While a large amount of TA is adequate, a good standard and with exclusive use of facilities, much of it is not, and includes shared facilities – such as those found in B&B. For families who find themselves living in B&B, and other inadequate forms of TA, the effects can be traumatic and long lasting. Children can be deprived of basic opportunities, such as somewhere to play, study and sleep in peace; adults’ self-esteem can be eroded and they suffer the heartbreak of trying to shield their children from the full stress of the situation, while being unable to provide meals, safety and a healthy living environment.

To address the problem of increasing numbers in TA the government must take both a short-term and a long-term approach to the challenge. In the short-term, there needs to be a boost to temporary accommodation funding, which will allow councils to acquire self-contained units that are of a good standard and located close to a household’s family and support networks.

But the key is to move homeless households out of TA as soon as possible and into stable, affordable properties in their local area. To do this, councils need a ready supply of affordable accommodation, which means replacing every social rented property that is sold through Right to Buy, building the level of affordable homes that the country needs, and ensuring the private rented sector is accessible and fit for purpose for those on low incomes.

This approach will not only help reduce the numbers living in TA, it will prevent people from becoming homeless in the first place, creating a virtuous cycle where TA is less under-strain and can function as an emergency service for when the worst happens. Alternatively, without the affordable homes we need we are on a steady ascent back to record levels of B&B use.