The Government’s new Immigration Bill – even more bad news for renters and landlords

Published: by Deborah Garvie

Last week, the Government introduced another Immigration Bill, which will have its second reading in Parliament on 13 October. The Bill will significantly weaken tenants’ protection from eviction, by making it possible for landlords to evict people who are deemed to have no ‘right to rent’, without the need for a court possession order. It will also create a new criminal offence for landlords who let to people without a ‘right to rent’, which will carry a maximum five year prison sentence for the worst offenders.

This new offence builds on reforms to the rental market introduced in last year’s Immigration Act, which aimed to make it harder for illegal immigrants to settle in the UK. For the first time, it became unlawful for a private landlord to let to a person who cannot prove they have a ‘right to rent’. We have consistently argued that some households (especially those who have fled domestic violence or been illegally evicted), can have good reasons for not having all the documents required to prove they are British or have valid permission to be in the UK.

During the passage of the Immigration Act in 2014, assurances were made to Parliament that that the scheme would be thoroughly and transparently evaluated before any decision on a national roll-out took place. In December last year, the ‘right to rent’ scheme was rolled out in the West Midlands, as a test-bed for countrywide implementation this year.

The Home Office has yet to publish the results of this evaluation, but the Government announced last month that it will go ahead with a national rollout of the scheme anyway.

The further measures in this year’s Bill aim to ‘__control immigration, making sure we put hard working British families first’. While the Bill’s effects on immigration remain to be seen, it will almost certainly have an impact on the thousands of families who now rely on the private rented sector for a home.

Firstly, there is a real danger that the legislation could create further barriers for people trying to get a private rental home. Recent Shelter research shows that there are already significant barriers facing benefit claimants: close to two-thirds (63%) of landlords either refuse, or prefer not to, let to households receiving housing benefit. When it comes to families, 36% of landlords won’t or prefer not to let to families with children.

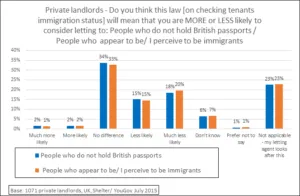

This same research found that around half of landlords who make decisions on letting to migrant tenants say the Immigration Act ‘right to rent’ checks are going to make them less likely to consider letting to people who don’t hold British passports or who ‘appear to be immigrants’. Over a third (37%) already admit that ‘It’s natural that stereotypes and prejudices come into it when I decide who to let to’, even before the ‘right to rent’ is rolled out UK-wide. This finding is echoed by JCWI, which recently published its own evaluation of the impact of the West Midlands ‘right to rent’ trial**.**

This shows that ‘right to rent’ checks are making it harder for people to find a place to call home – including those who have every right to rent in the UK. It also provides evidence that landlords are prepared to discriminate against those with a complicated immigration status and those who cannot provide documentation immediately.

With landlords now facing a criminal record for letting to those without a ‘right to rent’, as others have pointed out, they are likely to become even more risk-averse: not being able to produce obviously acceptable documents right away will lose people tenancies.

Secondly, the proposed eviction measures could also make matters worse for renters. The Government intend to exclude those deemed not to have the ‘right to rent’ from aspects of the Protection from Eviction Act 1977 and the Housing Act 1988. Eviction will be ‘triggered by a notice issued by the Home Office confirming that the tenant no longer has the ‘right to rent’ in the UK. The landlord would then be expected to take action to ensure that the illegal immigrant tenant or occupant leaves the property’.

There’s an obvious question about how the Home Office will locate landlords – many a housing enforcement officer will wish them well with that task. But, once in receipt of the notice, the landlord will be able to evict tenants, after a short notice period, without the need for a court process for repossession (a bailiff’s warrant is required).

It’s not just those without a ‘right to rent’ who could suddenly be evicted. It could result in no-court eviction of joint tenants (including student flat-mates) with a ‘right to rent’, or families with children, who should have a ‘right to rent’ but are subject to an erroneous notice because of anomalies with their immigration status, perhaps because of administrative delays at the Home Office itself.

The Protection from Eviction Act was designed to ensure that people cannot be turned onto the streets by their landlord without the oversight and approval of a court. This protection gives people time to show that they shouldn’t be evicted, for example by proving that they have the ‘right to rent’. As the Government’s own advice to tenants states ‘it does this in two ways: by making harassment and illegal eviction a criminal offence, and by enabling someone who is harassed or illegally evicted to claim damages through the civil court’. This protects renters from landlords who threaten to evict them by force.

Unless it is reconsidered, the latest Immigration Bill proposals threaten to increase the discrimination renters’ face, making it harder to find a home. And it could leave families with children unable to prove that they have a ‘right to rent’ in the UK at greater risk of eviction and street homelessness.