Living in London offers a wealth of ways in which to experience housing misery. You might be desperately struggling to find a half decent home that you can afford. You might be shelling out most of your wages to rent something barely worthy of being called a home. You might be languishing in temporary accommodation – as over 50,000 Londoners are currently.

If you’re one of the majority of Londoners who’s not being well served by the capital’s disastrous housing system – and if you’ve given up hoping that those glossily photo-shopped hoardings around building sites with abstract nouns pasted across them will ever reveal anything you could dream of actually living in – you’d be forgiven for imagining that it’s all hopeless. That nothing will ever get London building the homes we need, or improve our private rented sector, or protect our affordable housing.

And there are lots of good reasons for gloom – especially as the Housing & Planning Bill going through Parliament now looks set to make things a whole lot worse on many fronts. But on one outlook of the crisis facing the city, there are at least some grounds for optimism.

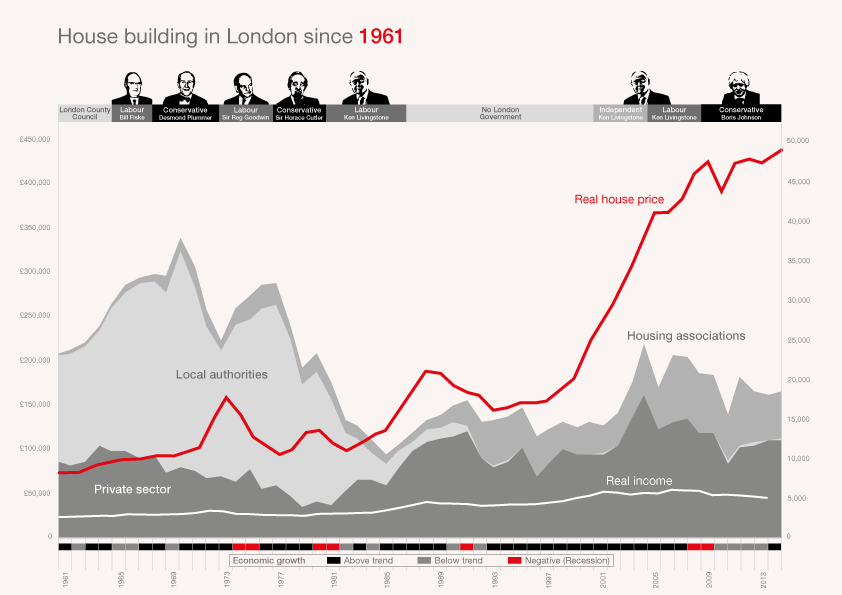

Most aspects of London’s housing crisis – or ‘challenges’, as politicians are wont to call them – have their roots in decades of undersupply. We simply haven’t been building anywhere near enough homes for ages – and despite lots of promises from all sides to build more, we’re still only running at barely half the 50,000 new homes needed each year.

Of course, runaway house prices, rising rents and insufficient building is not just a London story – although in the capital the sheer scale of prices dwarfs that of anywhere else. At Shelter, we’ve been highlighting the failure of successive governments to build enough homes for ages. And we’ve done our best to set out effective, practical ways of transforming our woefully dysfunctional housing supply system: before the general election we set out a comprehensive programme for doubling house building over the life of this parliament.

But after years of banging on about the need to build more homes across England, and countless interviews, conferences, reports and blog posts, one message I keep coming back to is this. At its most basic you need three things to build a home:

- land

- money

- and planning permission.

The fourth factor is then having the right actor to pull these three things together and make development happen.

The fundamental problem in most of England is that these three factors are all controlled by different people at completely different levels. Planning permission is granted (or not) by local authorities – while plans themselves are increasingly made at the neighbourhood level. Land is mainly held by private owners, or national bodies in the public sector. And the money to invest in affordable homes and infrastructure is controlled by central government.

So it’s little wonder that house building is such a slow, messy, unpredictable and unlovely business in England. The right powers and resources simply aren’t co-ordinated at the right spatial level.

Happily, there is one glaring exception to this sorry state of affairs. In London, the Mayor controls all three of these levers. The Mayor writes the London Plan – the only proper regional plan in the country – which determines where homes can go, and what affordable housing policies should be. The Mayor also gets to decide on major planning applications. The Mayor controls the affordable housing budget, and can decide what type of homes to fund, and which schemes to support. And the Mayor, via the GLA and TfL, also owns a fair amount of land in the capital. All that’s needed is to bring these together under the right agency – and here again, the Mayor has the unique power to create Mayoral Development Corporations, like the one that successfully built the entire Olympic Park development in record time.

None of these powers is perfect, or absolute. But they are far stronger than those of any local authority leader – and most importantly all these levers sit at the same place, in the Mayor’s office in City Hall.

That’s why we should be cautiously optimistic. All the candidates to be London’s next Mayor have pledged to address the housing shortage. Whoever wins will have their hands on all those levers. Using them intelligently is not a simple matter, and will require some tough choices about where to find the space for homes and what to fund. As our recent report with Quod shows, there are no easy options for accommodating London’s growth, only hard choices, and (let’s face it) politicians of all stripes do like an easy option.

But hard does not mean impossible, and this is just too important an issue to let ourselves despair – or let whoever sits in City Hall off the hook. The next Mayor really can fix this – if we make them try.

I do not understand how Shelter can help produce a report on London’s future housing without once mentioning the issue of tenure type. Almost all proposed development will be leasehold which has a major impact on both supply and demand. Without understanding what impact Commonhold could have suggests someone is making what may be false assumptions.

Shelter along with everyone else did not even have a vaguest idea of the property structure in London until 2014 when government were persuaded our structure is very different to that which has been historically assumed.

It begs the question what is the point of Shelter funding these sorts of reports when the basics are not understood.