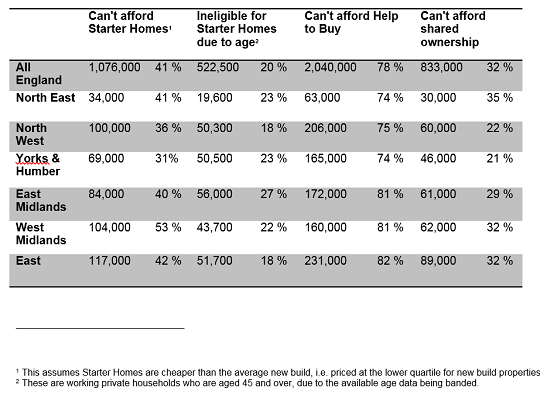

With the Autumn Statement looming, current funding for affordable housing is still largely reserved for Starter Homes and shared ownership. This weekend we published new research that shows that almost a third, or over 830,000, of working privately renting households would not be able to afford any of the three main ownership products based on their income.

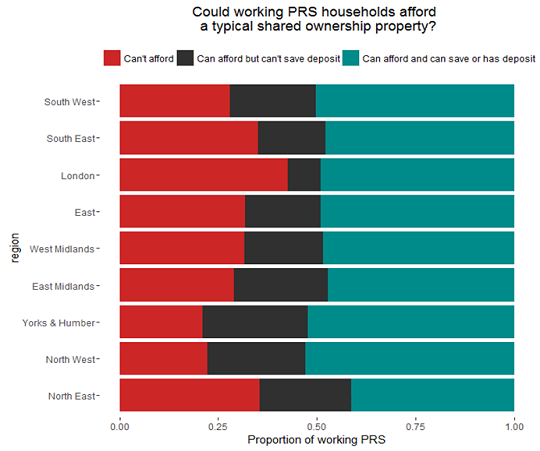

A further 20% of working private tenants are unlikely to be able to save up enough for a deposit on a shared ownership property. The incomes, work patterns and circumstances of these families vary from region to region, so a one-size fits all approach to help them out of insecure and expensive housing will not work.

So who are these left behind private renters? This blog summarises our analysis for those interested in the detail.

Where are working renters left behind by ownership schemes?

In a recent DCLG committee meeting, both Bob Blackman and housing minister Gavin Barwell referenced the role of products like Help to Buy and shared ownership’s ability to ‘make a really big contribution to helping people get onto the housing ladder’, particularly in London. But our analysis, based on the data from the Family Resources Survey, suggests that even shared ownership risks leaving behind anything from 21% of working privately renting households in Yorkshire and the Humber to 42% in London.

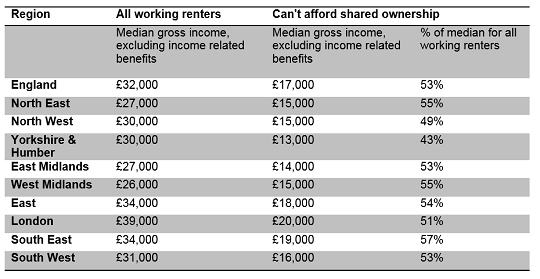

Working renters in a JAM

This assumption that shared ownership can fill the gap left by Starter Homes or Help to Buy is understandable given the lack of insight in to the real households that these policies are aimed at. Our research shows that it is likely to leave behind working privately renting households earning around £17,000 on average; in other words, the lower end of Theresa May’s ‘just about managing’ families. Incomes range considerably across the country, however, from £13,000 in Yorkshire and the Humber to £20,000 in London.

Varied work lives, varied circumstances

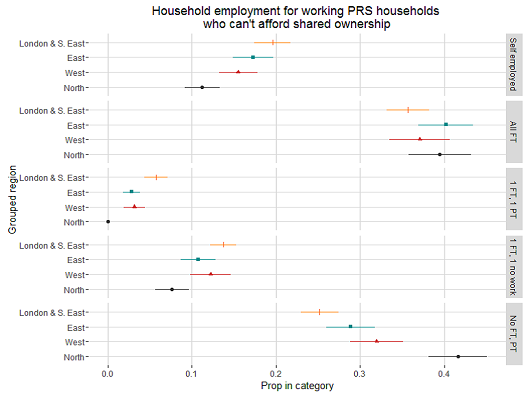

Across the country, 53% of left behind working private renting households have at least one adult in full time employment. In around 40% of these households, all adults work full-time. This, however, masks variations in work patterns that can help to explain why their incomes are so different across the country.

In London and the South East around in around 20% of left behind households all their work is from self-employment compared to around 10% in Northern regions. Conversely, in Northern regions 40% are only in part-time work, compared to 25% in London and the South East.

Some of these households may face very real barriers to increasing their incomes by working more hours. For example, left behind households are twice as likely to be headed by a single parent compared to all working private renters. In the North, where part-time work is more common, this figure is 25% compared to 15% in London and the South East.

Left behind households also have characteristics that could make it harder to move to cheaper areas. These include having at least one school-aged child (40%), having a disabled household member (20%) and even caring for people outside their household (7%). It is therefore no surprise that 85% of left behind renting households describe their housing costs as a burden or struggle and 45% report that they are a heavy burden.

Savings matter too

Even amongst private renters who could theoretically afford shared ownership based on their income, around 40% have no savings. An additional 475,000 of households who would be eligible for at least shared ownership are unlikely to be able to save up a typical shared ownership deposit. This means shared ownership is likely to be out of reach for half of working privately renting households in England.

Investment in housing must meet the needs of real households

Understanding the realities of renting families across the country can ensure government support is better focused on meeting their needs and aspirations. What is clear is that geographical differences in both house prices and households themselves mean a one-size fits all approach to solving the housing crisis and boosting home ownership will not work. The Autumn Statement represents a chance to fix this by rebalancing funding towards a better mix of ownership and rental housing.

Following a recent report on the shortage of affordable rented housing by the Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors I wrote the following letter;

I noted in your report on the shortage of rented property the following 2 points;

1 Pension funds should be given tax breaks to fund large scale rental properties

2. Councils encouraged to release brownfield sites for building homes for tenants

Could I suggest an alternative to the use of Pension funds. This would be the issue of a Government Pensioner Bond, directly available to anyone over the age of 65, which would be used exclusively to build property for rent. The property would be state owned and managed. The bond would be repayable on the death of the holder. It would yield 5% per annum and be secured against the properties purchased. Only the original investment would be returned, no increase in the value of the property, this would remain with the state. The bond could be repurchased by another person reaching 65 years. Such a bond would be very attractive to pensioners as an alternative to using their pension savings to buy an annuity which typically pays no more than 3% and the capital is lost on death.

I got this idea originally because of the number of offers I receive, as a pensioner, from private developers in the UK for investment in buy to let properties offering net rent returns of 6.9 to 15%. Such offers appear to be highly speculative and obviously involve the higher end of the market. To get a 5% net return from the rent received for affordable properties presupposes that each unit can be built for a low price. At this point your suggestion that councils release brownfield sites would become relevant.

With regard to the amount of pensioner savings that are available already for such a venture, I am quoting from a recent newspaper article on the subject; “Over the full year, there were 300,000 lump sum withdrawals from pension pots, averaging £14,500 each, according to the ABI. There were also 1.03m drawdown payments, averaging £3,800” in the last year 7.8 billion pounds have been released.