Reducing homelessness: The bill and beyond

Published: by Jenny Pennington

In 2015, Wales changed the way it provides support to people threatened with homelessness. This led to a significant reduction in homelessness acceptances. The Homelessness Reduction Bill would make the English homelessness safety net look more like the safety net in Wales. We feel that this would ensure more people get help to try and resolve their homelessness. However, it will not necessarily have the same impact in England as it did in Wales. Here we set out why this is, and what else is needed to reduce homelessness, and to unlock the potential of legislative change in England.

In 2015, Wales introduced a legal duty on local authorities to offer help to every eligible household threatened with homelessness. Councils have to take action to try to prevent these households becoming homeless, or to relieve their homelessness if they have nowhere to stay. It’s not the same as a right to be rehoused but it means people not eligible for the full rehousing duty can’t be turned away with nothing.

The introduction of this duty meant more people had their homelessness successfully prevented or relieved. This had a major impact on the number of households who were subsequently ‘accepted as homeless and in priority need’. This dropped by 67% in one year.

Looking at these numbers, it might be easy to assume that implementing a similar change in England will have similar results. However, while the Bill has many merits, we feel there is reason to be highly cautious about whether we will see a similar reduction in homelessness as we saw in Wales. This is for three reasons.

English councils are already doing a lot of the work that the Bill will legally require them to do

Firstly, English councils are already doing a lot of prevention work on a non-statutory basis, and have been, with support from the Department of Communities and Local government (DCLG), since 2003.

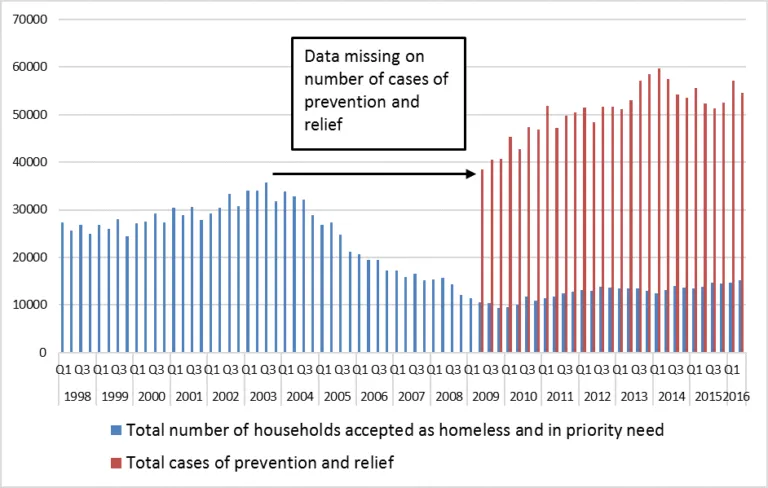

As a result, English councils have already banked a lot of the reductions in homelessness acceptances that prevention can bring. As the graph below shows, the introduction of this approach in England in 2003 was followed by a steep drop in the number of households accepted as homeless and in priority need (the blue bars). Independent analysis and evaluations of this change found that the introduction of prevention measures was the main reason for this decline. Bringing this work under the accountability of a statutory duty is very welcome and one reason why Shelter support the bill.

The English experience shows that changing local authority practice alone doesn’t always reduce homelessness

We only have one year’s worth of data into how statutory prevention measures can reduce homelessness in Wales. But we have almost fourteen years of data from England, and this evidence is more mixed. The reduction in homeless acceptances in England has not been sustained across the last decade. From 2010 onwards, the number of households accepted as homeless and in priority need started to go back up. Importantly, this was despite the fact that councils were actually doing an increasing amount of prevention work at this time (the red bars in the graph above).

This experience illustrates clearly how factors other than the support provided by councils’ housing departments have a major bearing on how many households become homeless. Our recent analysis of homelessness found that rising homelessness is being driven by growing problems with the affordability of housing combined with cuts to housing benefit. These problems seem likely to worsen in the future. Our analysis shows that by 2020, four fifths of areas will be unaffordable to people on housing benefit. Preventing homelessness in this context will require a herculean effort.

In order to reduce homelessness, we need to look beyond changes to law and local authority practice. Only by really embracing the culture that the Bill aims to promote will all people facing homelessness feel that the council at least tried to help them find a solution. Critically, we need to build the affordable homes we need and fix our broken welfare safety net. In the short term, we need to make sure that councils have the resources they need to overcome these challenges. This leads us to the final reason why we might not see the same impact in England as seen in Wales.

The Department for Communities and Local Government is providing less funding to English councils than the Welsh government provided to Welsh councils

Wales sees fewer cases of homelessness than England. Last year, Birmingham and Leeds councils alone provided more help to homeless households than all Welsh local authorities combined. London councils took more than two and a half times as many actions as all Welsh councils. This is particularly important to recognise when looking at the funding needed to achieve change in each country.

In the first year that this system was introduced in Wales, Welsh councils received £5.6 million and took successful action to prevent or relieve 7,707 cases of homelessness. If you look at the funding that will be provided to all English councils (both current and additional) to help them prevent homelessness in the first year of implementation, and their current caseload, then English local authorities will have £115 million to prevent or relieve 270,990 cases of homelessness. This is equivalent to 58% the amount, or £302.24 less, per case than Wales. Admittedly, the funding in Wales was to assist in the transition to a prevention approach, which English authorities have already made. But the law change in England will require existing processes to be formalised, such as personal housing plans.

English councils could set themselves the more ‘manageable’ target of matching Welsh councils and reducing homelessness acceptances by 67%. But even hitting this target would be tough. English councils would have to do it with two thirds (63%) of the funding needed by Wales per case.

Critically, these calculations (above) are based on the assumption that the number of people coming forward for help would stay the same. But, the Bill deliberately increases the pool of people who may seek help, even before rising homelessness comes into play. This laudable aim to help more people is likely to stretch these resources even thinner.

We need take action to reduce homelessness

We feel that the Homelessness Reduction Bill, and the extra funding provided to councils to implement it, will make vital improvements to homelessness legislation and lead to critical support being made available to more people at an earlier stage. While it won’t guarantee everyone a home, it will make sure no one feels they were turned away without any help.

But we have to be realistic about the short and long-term reduction in homelessness that it will achieve. This is why we support the call of the Local Government Association for the Government to commit a review of the Bill’s impact two years after implementation, to assess whether the legislation and its implementation funding is delivering on its ambition to improve services, options and outcomes for people threatened with homelessness.

In the meantime we urge the government to consider the main lesson of the Welsh and English experience of prevention services – that we will not reduce homelessness until we reduce the number of people having to seek help in the first place. To achieve this, the Government must prioritise building the affordable homes we need, reforming renting so that fewer people face eviction and ending the freeze to local housing allowance. This is essential to ensuring that people on low incomes can escape not just the reality, but also the threat of being without a home.