‘Landlord exit’ part 1: more than one in ten landlords leave the market every year

Published: by John Bibby

This is the first of three posts looking at the reasons for, incidence and implications of private landlords leaving the market. This part will use new research to quantify landlord churn. Part two – to be published tomorrow – will consider what causes it. Part three will look at the options for reducing the impact that landlord churn has on tenants.

For a long time, landlord churn – the rate that landlords enter and leave the market – has been woefully understood in England.

Through tax data we have had a pretty good understanding that the total stock of landlords has been growing rapidly as the number of rented properties and private tenants has taken off.

But we have not had a good idea of the churn that’s been going on under the surface of this growth: the flow of people starting and stopping being landlords each year.

Using new research by YouGov, we now feel confident that we can estimate the rough scale of landlord churn – and it’s big.

Before we get to that, however, we need to talk about why it matters.

Landlord churn contributes to evictions and homelessness

A landlord exiting the market will not always have this impact on tenants, because sometimes they will do it when their property is already empty. But often there are already tenants living in the property when a landlord decides to move back into it themselves or sell. And often they don’t sell with their tenants in situ even if they’re selling to another landlord.

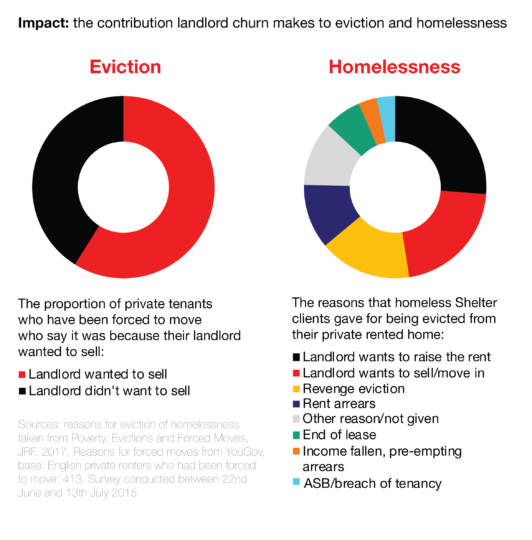

We know from previous research that this makes a substantial contribution to eviction and homelessness.

In 2015, research for us by YouGov found that 59% of private renters in England who had been forced to move out of their home by their landlord said that it was because they wanted to sell the property. The government’s most recent English Housing Survey had a similar finding, with 63% of forced moves caused by the landlord selling the property.

At the very least, being forced to move home can mean substantial moving costs, forcing more than a third of renters who move into debt. It can mean stress, inconvenience and the loss of a place where you are settled.

For families with children it can mean even greater stress and the risk of having to move your child’s school.

Ultimately, it can lead to the evicted household becoming homeless.

New research by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation backs this up by suggesting the significance of the contribution landlord churn is making to people becoming homeless. Of the homeless Shelter clients included in their study, landlords wanting to sell or move back in was the second most common reason that they had lost their private rented home, triggering their homelessness.

How large is landlord churn?

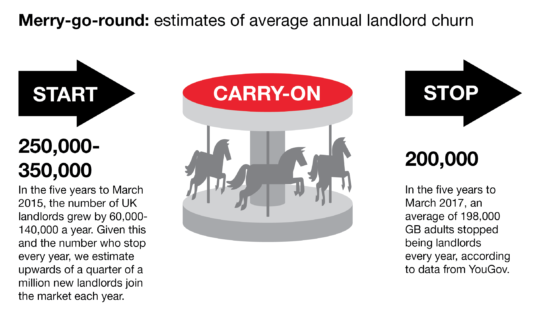

We can confidently estimate that at least one in ten landlords exit the market each year, and that they are replaced by even more driving the total growth.

We have made this estimate based on the number of people who say they have previously been a landlord and when they stopped. A survey of almost 4500 people for us by YouGov found that 7% of GB adults have been a landlord before, but aren’t anymore, the equivalent of around 3.5 million ex-landlords. The chart below shows that 29% of these have stopped being landlords in the five years to March 2017, equivalent to almost a million people and an average of almost 200,000 a year – at least 10% of the number thought to be landlords at the moment.

Of course, the fact that the total number of landlords has continued to increase, even while a large number of landlords have been leaving the market every year, means that even more people are starting to let out property every year.

Figures from HMRC show that the number of tax-paying landlords in the UK went up by almost half a million in the five years to 2014/15, to take the total to more than 1.8 million. And while this figure is definitely an underestimate (because some landlords evade tax by not declaring their rental income and others own their properties through company structures) it’s based on the best data we have.

We thus estimate that while around 200,000 landlords have stopped being landlords every year, they have been more than replaced by 250,000-350,000 people who have started becoming landlords every year.

These numbers are not exact. As with the total number of landlords taken from tax data, the number of those exiting the market is likely to be an underestimate, as it doesn’t capture anyone who has stopped being a landlord and then started again. Furthermore, the periods covered do not exactly align and the area covered by the tax data (UK) does not exactly align to the survey sample (GB).

There are also lots of things that the numbers don’t tell us. For example, they don’t tell us how many properties the landlords that exit the market own or give any insight on existing landlords expanding their portfolios.

However, the finding that there is a consistent flow of at least one in ten landlords leaving the market every few years is important. It suggests England’s stock of landlords are inherently in flux. And as the number of renting from private landlords grows this is contributing to the growing number of people losing their home and becoming homeless.

In my next post tomorrow, we will consider what is driving this landlord churn – and whether it is caused by the oft-heard threat that landlords ‘flee the market’ in response to policy change.