‘Landlord exit’ part 2: is the threat of a landlord exodus real?

Published: by John Bibby

This is the second of three posts looking at the reasons for, incidence and implications of private landlords leaving the market. Part one used new research to quantify landlord churn. This post considers what causes it. Part three – to be published tomorrow – will look at the options for reducing the impact that landlord churn has on tenants.

At some point, you are bound to have read a screaming headline warning something like ‘one in 10 landlords will leave the market if…’ This threat of a landlord exodus has been invoked as a reason not to implement countless regulatory changes to private renting over the years.

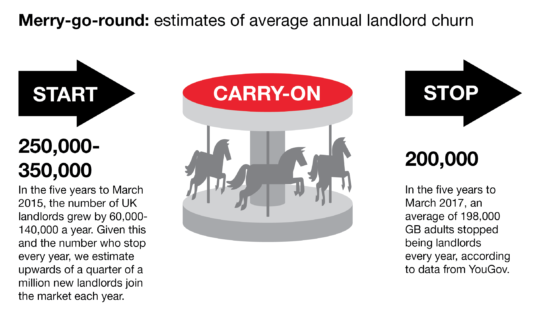

In the first post in this series, we learned that one in ten landlords already leave the market every year, only to be replaced by others – and more on top.

So in this post we will look at whether this past landlord churn was – like the scare stories have suggested – a response to policy change and how likely landlords are to exit the market in response to future policy change.

Over one in 10 landlords *already* leave the market every year

Despite a growth in the total stock of landlords over recent years, we are confident that there is a fairly consistent trend of more than one in ten landlords leaving the market. And this churn is already making a significant impact on evictions and homelessness.

It is clear that this current level of landlord churn is in the main not caused by hostile government policy changes or economic change, as it has occurred in some of the most benign market conditions imaginable. For example, over the last five years English landlords have generally benefited from:

- the lowest interest rates since the Bank of England was established

- the lightest-touch regulatory regime of any comparable market in Europe

- market rents that have risen more than inflation

- a growing number of private tenants and demand

- substantial year-on-year national house price growth

Furthermore, if existing landlord exit was being caused by draconian regulation, we would not expect even more landlords to enter the sector each year.

So what is causing existing landlord exit?

CCHPR found only limited influence of recent policy change on current landlords, but that some would choose to sell up in response to a change in personal circumstances. One landlord in the research put it this way:

‘The decision to sell would be when I get fed up doing it. I’ll be 80 next year. I don’t want to be climbing up roofs and unblocking gutters forever.’

Changes in personal circumstances appear to have been a significant driver of landlord churn in recent years and corresponds to the picture of landlords we have from our previous research.

We know from previous research that a large proportion of private landlords are older people and – in any given year – may want to retire from being a landlord. 35% of current landlords are over the age of 65.

We also know that a quarter of landlords only got into the business accidentally and may not be in it for the long-term.

13% of landlords only started letting their property because they wanted to sell but couldn’t. Many of them are still likely to want to sell in any given year. Another 12% of landlords say they started because they inherited the property and may have no interest in doing it for the long-term.

Moderate policy change appears unlikely to prompt a future landlord exodus

We also asked CCHPR to look into the future, to consider whether policy or economic change would be likely to accelerate the existing rate of landlord exit. They posed a range of different potential scenarios to landlords, such as an interest rate hike. But even future change appeared unlikely to significantly influence the rate of landlord exit.

The research concludes:

‘…the landlords interviewed showed a strong commitment to the private rented sector and are not likely to leave in a hurry… Falls in house prices, or reduced profits, are unlikely to make many sell up… Landlords appear, overall, to respond to changes in the economic or fiscal environment by changing the rate at which they purchase new properties, rather than sell existing stock.’

The research shows clearly that landlords are a heterogeneous group, with very different motivations and business models. For example, there was a clear difference between large institutional landlords and those who only owned a few properties. So it is hard to generalise about them.

However, the landlords interviewed are at least as likely to hunker down in response to a future change in policy or economic conditions as sell up and exit the market.

This tallies with the findings of recent research by the LSE for the Council of Mortgage Lenders. They found that current landlords who are thinking of selling-up are more likely to say it’s because they are approaching retirement or because they ‘did not intend to be a landlord’ than because of ‘regulatory burden.’

Clearly, some policy change could prompt particular landlords to quit the market – and this may be particularly true if they also happen to be nearing retirement or not committed to the sector. That’s why, for example, we have called for the introduction of changes to mortgage interest rate relief for some landlords to be kept under observation.

Furthermore, particularly draconian policy change may have other wider effects. Our previous research has shown that trying to force private landlords to dramatically cut rents could reduce the total number of rented properties over a short period, for example.

However, this research suggests that in general the link between moderate policy change and landlord exit is loose and not as important as changes in personal circumstances.

As a result, the solution to landlord exit isn’t simply a matter of leaving the market to look after itself. Deregulation doesn’t stop people aging.

So tomorrow, in the final post of this series, we will consider what the real options are for reducing the impact that landlord churn has on tenants.