Leasehold abuse – why builders won’t mind if we ban it

Published: by Catharine Banks

Earlier this year, we wrote about the growing issue of exploitative practice in the leasehold system. We were pleased that the government’s White Paper pledged to tackle this problem, and that the need for action was reiterated in party manifestos. In July, DCLG published a consultation on ‘Tackling unfair practices in the leasehold market’, to which Shelter will respond.

Many homebuyers have been subject to incredibly unscrupulous practices – from spiralling ground rents to unreasonable charges, and freeholds being sold on without notifying the leaseholder. We support the government wholeheartedly in their attempts to tackle this, and make leasehold homeownership much fairer. As the consultation document itself sets out, there are situations in which leasehold is a suitable tenure, such as Garden Villages, or community land trusts more broadly. But for the leasehold model to be a success, accountability, transparency, and a vision for long term stewardship are critical.

Clearly there is decisive action to be taken where these principles are not in place, and the abuses of the system we’ve seen in recent years treat homeowners as nothing more than an income stream. Of course housebuilders should make a reasonable return when building homes – they have a responsibility to their shareholders to do so. However, this should not be to the detriment of the people who will live in those homes. The goal of building homes should first and foremost be to benefit the people who will live in them – this principle is at the core of Shelter’s New Civic Housebuilding.

Looking beyond the specific issue of leasehold, there was one quote in the Times coverage of the consultation which particularly struck me:

[A]n industry insider told The Times that builders were unlikely to fight the plans, with many awaiting regulation because they felt unable to give up the practice unilaterally without putting themselves at a commercial disadvantage to rivals.

“The worst of these leases are very difficult to justify even for builders,” the source said.

Sajid Javid reiterated this in his comment piece for the Times, stating that some housebuilders “have told me that they’d be happy to stop unjustified use of leasehold, but can’t afford to do so unless their competitors take the same step.”

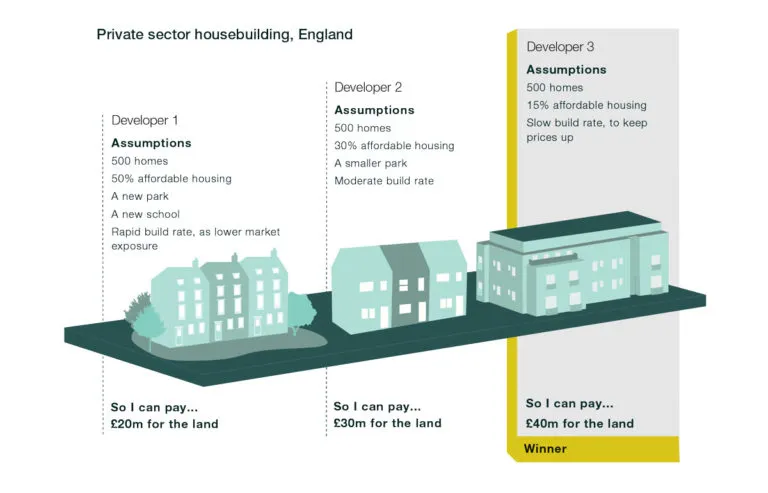

This prisoner’s dilemma goes to the heart of the problem with the speculative housebuilding model. Its competitive nature means that anyone who tries to do something different – or better – can never win against its most aggressive participants. Here, we see this manifested in abuse of the leasehold system. However, it is replicated throughout the system – most notably when bidding for land to build on in the first place:

Whether it comes to affordable housing, the provision of infrastructure and community facilities, or the use of unfair leasehold contracts – the combative speculative housebuilding system we rely on simply doesn’t deliver for ordinary people.

We can’t wait for the system to fix itself – we need clear and decisive intervention. We are pleased to see the government starting to make good on its promise to fix our broken housing market.