7 things to consider when communicating about welfare

Published: by Tilly Williams

You may have seen mine and Paul’s previous blogs about our campaign to soften public attitudes towards welfare, so that political parties will feel less emboldened to implement further cuts, and will work towards improving the system going forward.

We’ve just finished our second pilot of the campaign. We learnt from our target audience and applied some behaviour change theory to our campaigning approach. Here’s seven things we’ve learned (in no particular order).

1. Be authentic

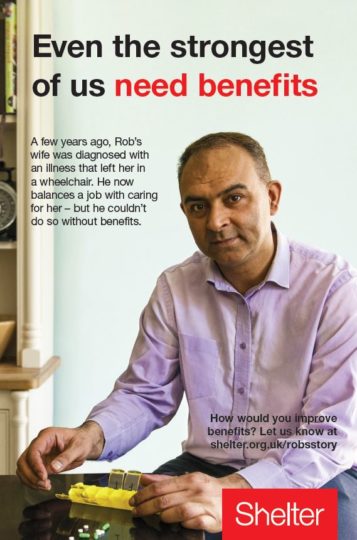

The public can tell when someone looks too staged, too polished, and they pick up on little things even in the background of photographs. In our most recent pilot campaign, we’ve made our case studies and our photography as authentic as possible, and they’ve performed much better with our audience.

2. Social norming – we all do it

One big way we can achieve a change in attitudes about something is to convince people that the change is ‘normal’ – reverting to something that’s a generally accepted norm in society. Through real-life stories, our campaign tried to show that benefits are just a part of everyday life. People may dip in and out of them over their lifetime or they may need help longer-term help because of their particular circumstance.

As much as paying the bills, doing what’s best for your family, or making ends meet.

3. What’s the first thing you think of when I say ‘heuristics’?

Part of the reason that some people have such negative, entrenched views about welfare is because of heuristics. This means that when people think of a particular topic, their brains takes a short-cut to an instant response about it – they do this because we don’t have time to go through all the information so our brains filter out information we think is irrelevant. For welfare, this can manifest itself in the recall of a tabloid article about benefit ‘cheats’.

We want to interrupt this tabloid narrative, and give people a ‘new normal’ to which their brain can refer. The idea is that instead of remembering the tabloid article, they think about their own situation, or those of people they know. Or at least, remember both, and have to think about it a little bit more.

4. Cognitive dissonance – yes or no? Or both?

Our campaign aims to shake up the cognitive dissonance that leads people to believe two seemingly contradictory viewpoints. The headline of our campaign was ‘even the strongest of us need benefits’. We did this to counteract some of the negativity created by the right wing press, and this went down really well in the focus groups we ran with a few people remembering it unprompted, something that’s quite rare, particularly in a small pilot.

5. Who is the messenger?

It would be easy for us to shout about how everybody should have access to a safety net when they need it. But a lot of the time, people won’t listen to us. It may be because they think we’re asking for money, they have a distrust for charities, or they simply don’t know who we are, or what we do.

By letting real people – who have experienced the welfare safety net – tell their story and speak for themselves, it makes our message much more powerful. It also shows we’re being honest and authentic.

6. Now is the time

The work we’ve been doing feels particularly relevant at the moment. The British Social Attitudes survey shows a slight uplift in the number of people in favour of redistribution of wealth – currently at 43%. There has been talk of a backlash against austerity measures. More and more people are aware of the inequality in our society. These things mean the time is ripe for us to start a conversation about the need for a decent welfare safety net.

7. It’s hard…but it can be done

It’s always going to be very difficult to make people think differently about welfare, especially when we’re battling against years of negative media coverage and anecdotal evidence. But our evidence shows that there can be a subtle shift in opinion, from which we can build. We’ve seen really encouraging results from our pilots, which have shown us that a small but significant minority (around a third to a half, depending on case study) of people have started to shift their opinions because of our campaign.

There’s so much more to be done and we’ve got a long way to go, but our results look promising. We look forward to talking to other organisations about our findings and sharing what we’ve done so that we can begin to work towards a welfare safety net that works for everyone.