Smashing avocados, not the housebuilding targets

Published: by Toby Lloyd

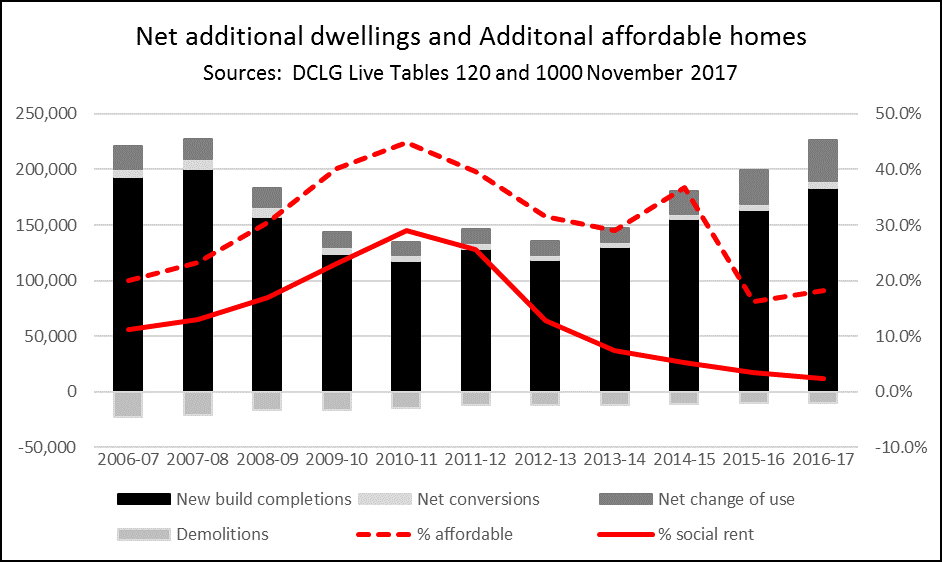

As was widely expected, today’s net additional housing supply figures showed an increase in the number of homes provided in England. A total of 217,350 ‘net additional dwellings’ were provided in 2016–17 in England, the highest figure since 2007–08 and the fourth year in a row that this measure has increased.

A small step

This is undoubtedly encouraging, as those new homes are urgently needed. Secretary of State Sajid Javid was well within his rights to herald the increase as a positive sign – but he was also right to say that they are ‘are only a small step in the right direction’ and that ‘what we need now is a giant leap’.

And unfortunately these figures are a long way short of a giant leap. There are at least three reasons to be wary of complacency about this uptick in house building.

Firstly, it’s one year of supply that’s still not high enough, so the targets are a long way from smashed. And it’s up from a very low base. House building has been in the doldrums for decades: today’s figures don’t quite reach the level of 10 years ago, that peak was itself far below the previous peak in 1988, which in turn was below the peak in 1979. To claim that today’s figures are some sort of record requires a very short timescale. The truth is that housing supply has been ratcheting downwards with every turn of the boom-bust housing market cycle. We need to be building a minimum of 250,000 homes, every year, for decades, to make up the backlog.

Storing up trouble

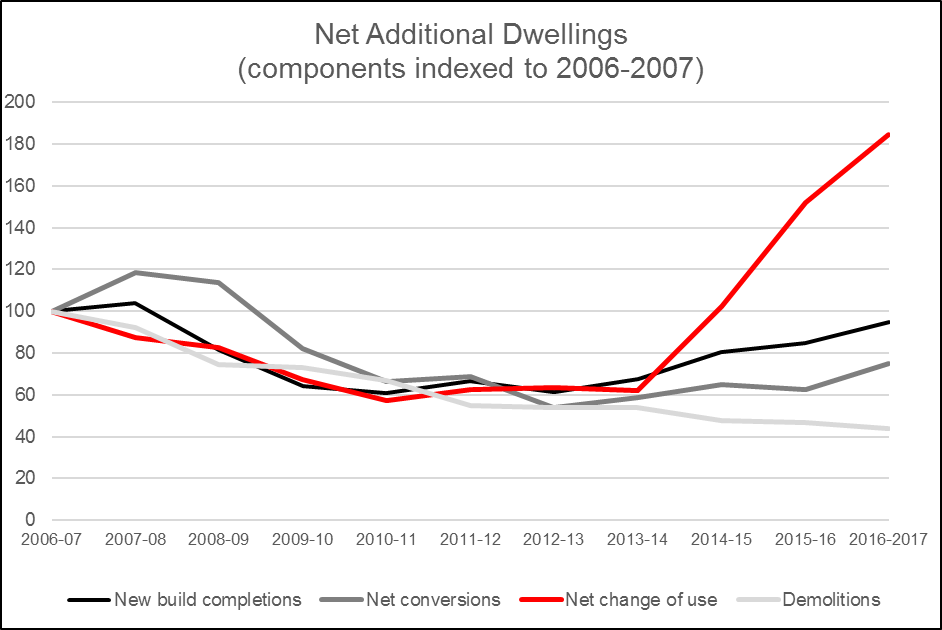

Secondly, a lot of these net additions are not from new building at all. Many come from the redevelopment of existing buildings. These broadly fall into two categories:

- Conversions are where existing homes are subdivided into two or more homes. This creates an increase in the number of ‘housing units’ but no increasing in the amount of housing space. There is a limit to how far we can squeeze people into smaller spaces. Conversions may well be the right thing to do, but we can’t treat them the same as genuine new additions to the stock.

- Change of use refers to non-residential buildings being turned into homes. Again, this can be an entirely sensible move – but there are reasons to be cautious. Today’s figures show that 9% of the annual total came under the new ‘Permitted Development’ (PD) rights. These were created in 2013, and essentially allow the owner to convert industrial, commercial or office buildings into flats without having to secure planning permission.

The new PD rights have proved a bonanza for the owners of such buildings, which suddenly became much more valuable. And it’s definitely helped boost the supply: nearly 19,000 homes were supplied in this way, almost 9% of the total.

But there are critical flaws in the new system, as we’ve pointed out before. They have created a rash of substandard flats, as tired offices blocks have been hastily converted into bedsits, without the proper scrutiny of the planning system. There are real concerns that some of these blocks are becoming the slums of the future, with tiny rooms, inadequate day light and dodgy electrics. The fire risks alone are alarming.

The right to convert without seeking planning permission also means that there is no obligation to provide affordable homes as part of these changes of use. This is a massive oversight, to be polite about it, which means this new chunk of supply is not doing its bit to meet local needs.

How many are affordable?

This leads us to the biggest reason to be cautious about the new supply figures. The sad truth is that most of these new homes are simply not the ones that are most needed. Last week, the department released a different set of figures on affordable housing supply – which here means the full range of non-market tenures, from social rented, ‘affordable rented’, shared ownership and others. On this measure the total supply of affordable homes was also up slightly to just over 41,500. But that still made it the second-lowest figure in ages – it’s just that last year was a nadir. Even worse, the breakdown of that total showed that the most secure and most affordable type of affordable homes – those for social rent – was at the lowest level since the second world war.

Taken together, the two datasets reveal a rather less rosy picture than some of the industry cheerleaders have been painting.

It suits some in the estate agency business to blame the affordability crisis on young people having the temerity to buy avocado toast or sandwiches. It suits some in the house building industry to insist that the system isn’t broken and will smash the government targets – as long as those huge subsidies keep flowing, of course… The hard truth is that yes, we are building more than at the bottom of the slump, but the proportion and number of those homes that are truly affordable is heading for zero. And no amount of skipping lunch is going to make up for that.

- Read our blog on what next week’s Budget must do to turn this around