Homes for NHS workers… Possibly? Maybe? Perhaps?

Published: by Kate Wallis

Last year, the Department for Health commissioned Sir Robert Naylor to produce an independent report into NHS property – including how to make best use of its land. The resulting report flew under the radar of all but the most diligent, but it contained some incredibly interesting insights into what could happen to NHS land.

On 30 January, the government accepted the majority of Naylor’s recommendations. This includes utilising surplus NHS land to make a financial contribution to estate improvement. Now this sounds a bit technical, but it’s really important (we’ll explain why later on in this blog).

The government’s response also reiterated Jeremy Hunt’s commitment to giving NHS workers first refusal on any affordable housing built on former NHS land.

Using surplus NHS land to provide genuinely affordable housing for staff is common sense. With the NHS facing increasing staffing shortages due to housing unaffordability, and homelessness increasing across the country, making use of NHS land to help resolve the problems seems sensible.

But how this is done is critical. As we said at the time, there is a real contradiction in selling off public land to plug a funding shortfall– while also expecting it to provide affordable housing. Selling public land essentially works in the same way as the selling of any land. Developers (or land promoters) must bid in competition with each other, which forces them to make increasingly aggressive assumptions about what can be made from the site in order to maximise the price they can offer the landowner.

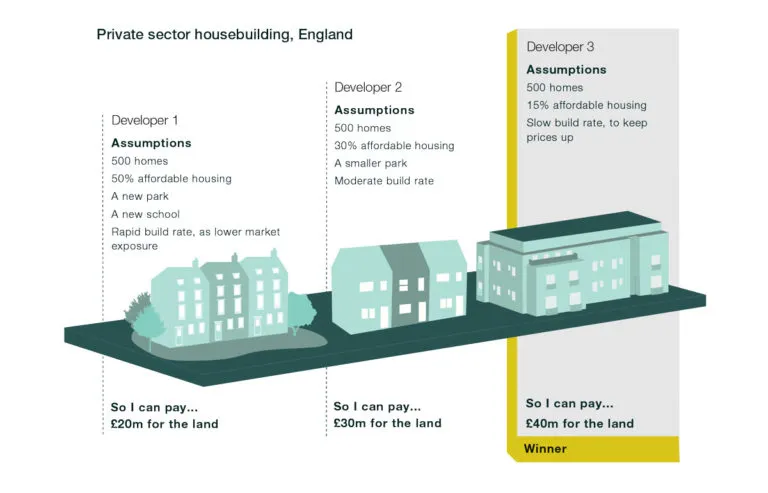

Many costs of development remain relatively fixed – building supplies, staff costs, an expected 20% profit – but the amount of affordable housing provision is flexible. This is because it is negotiated between the developer and the local planning authority (often using the viability loophole to reduce the affordable contribution). The result is that the developer which makes the most aggressive assumptions can offer the most for the land (as illustrated below), and will win the site – regardless of whether the seller was a private landowner or a public body like the NHS.

Why this matters

The government says it wants to build 3,000 affordable homes for NHS workers, so you might imagine that it would factor this in when selling NHS land – accepting a lower land price to allow affordable housing to be built on it. But when any public sector body sells land, it is required to seek ‘best value’. Treasury documents do say that social value can be taken into consideration, but in practice this rarely happens. After all, the NHS needs all the money it can get, and it can be difficult to attach a cash value to social good.

Sadly the 3,000 homes for NHS staff is not a firm commitment. The heavy caveats used in the government response clearly indicate that this is a negotiable goal, whereas the target to raise £3.3bn for estate improvement works is a pretty solid objective. The implication is that the improvement works are dependent upon public land being sold off for big bucks – and the affordable homes are a lower priority.

The current situation

Research from the New Economics Foundation shows that currently only one in five homes built on former public land are affordable. Even in cheaper areas, where a nurse could afford the mortgage repayments on a home, they would have to save 53 years for a deposit for homes built on land sold by the NHS.

In London, where the housing crisis is at its most serious, not a single home on former NHS land is affordable to NHS key workers. There is no indication that the NHS will be taking a different approach to the selling of land – and because of the best value rules, it will be incredibly difficult to. So we can reliably expect business to operate as usual and affordable homes to fall by the wayside.

In fact, the Naylor Review presented one option that makes it extremely likely that affordable housing will be stripped out. It indicated that substantially more money could be obtained for NHS land if the ‘risks associated with… affordable housing could be mitigated’. The risk referred to here is that affordable housing requirements lower the land price the NHS can expect to get. The Naylor Review didn’t explicitly advocate cutting affordable homes, but the fact that it is even considered a viable option demonstrates the problems with how we think about using public sector land. The fear is that the 3,000 homes for nurses will, like so many before, end up on planning departments’ floors – as developers overpay for land and then wriggle out of the commitments.

We are in the midst of a housing crisis which is already impacting the nurses and other key workers we rely on to keep us healthy and safe. So we must seize any opportunities to build more affordable homes – including using public land differently.

Fortunately, there’s an easy way to resolve the tension between housing needs and financial pressures facing our NHS, as we outline in our New Civic Housebuilding report. What public services really need is long-term revenue, not short-term capital injections. Instead of selling off the family silver, public agencies should be investing their surplus land into developments, giving them a reliable income stream for years to come. Holding long-term stakes in developments also gives public bodies a financial interest in delivering high quality schemes, as these generate better yields in the long run – just ask the Duke of Westminster. That means developing proper communities, with plenty of affordable housing, infrastructure and community facilities, that will grow and thrive into the future. This revival of the civic approach to public land is something the NHS is already (quietly) experimenting with through the Healthy New Towns scheme. The government really must take note of this shift in thinking– and stop the rush to sell off precious public land to the highest bidder.

- Learn more about loopholes in the planning system – specifically how they are costing us thousands of affordable homes