Inching towards better land value sharing

Published: by Toby Lloyd

These are exciting times for the select-but-growing band of Westminster-watchers interested in the role land value plays in our housing crisis – and in the wider economy.

Just before Christmas, there was the launch of a new All Party Parliamentary Group on Land Value Capture, chaired by Sir Vince Cable. Then the Communities and Local Government (CLG) committee launched an inquiry into the ‘effectiveness of current land value capture methods’. This sort of language may not set pulses racing, but it’s music to the ears of some of us. It’s pertinent timing – just as Sir Oliver Letwin’s review of build out rates begins, and as the government rewrites the National Planning Policy Framework.

The National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) sets out the rules local planning policies must follow – including the all-important ones on how much affordable housing and local infrastructure developments should provide. These rules are themselves the subject of a separate consultation, which all adds up to a busy time for policy geeks like me.

Land value sharing

When the local authority grants planning permission for new homes on, for example, a piece of ex-industrial land, the value of that land goes through the roof. That’s very nice for the landowner – but it’s the authority, acting on behalf of the community, that has created that uplift. So it’s only fair that the community should get some of that value back – especially as development also imposes cost on those who live and work near by.

New homes require new roads, new schools, new parks and other facilities to avoid overburdening existing services. So the planning system rightly demands that those profiting from the grant of planning permission contribute towards to those public benefits. Although it is the developer that gets the planning permission (and therefore pays the bill), developers know that they will have to make these payments – and should take that into account when paying for the land. In effect, the cost should be borne by the landowner, who will get a lower land price than they would have if no community benefits were required.

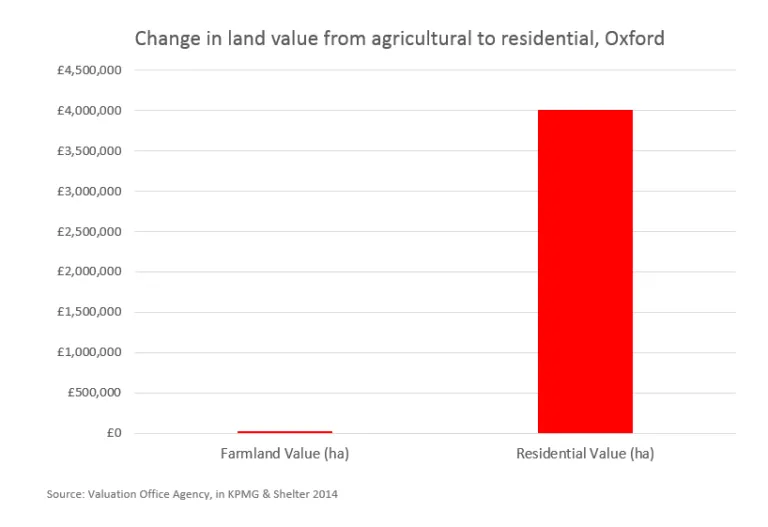

This doesn’t mean the landowner loses out either, because they still get to sell their asset for many times more than what it was previously worth. The uplift can be absolutely enormous– especially when agricultural land in high pressure housing market areas is released for housing.

Sharing land value

At present, there are two main mechanisms for sharing – or capturing, if you prefer – that land value uplift with the community. These are Section 106 agreements and the Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL). The first is usually paid in kind; the S106 agreement will specify how much affordable housing the developer must build alongside the private homes that make the money. CIL is a cash charge, which the local authority gets to pay for infrastructure.

Both of these approaches are fine in principle.The problem is how the two interact in the murky world of financial viability assessments.. In a nutshell, CIL payments are a fixed amount, which the developer knows they will have to pay in advance. But affordable housing policies are more ‘flexible’ – and challengeable. The S106 agreement for each planning application is negotiated separately between the developer and the authority. It’s not hard to guess what happens when the developer challenges the authority’s demands: the CIL gets paid and the S106 gets watered down. The affordable housing eats last.

Happily, this problem should soon be tackled, as the government intends to reform viability in the NPPF rewrite. In his Budget last November, Philip Hammond also proposed some improvements to the CIL system. These are essentially sensible measures to tighten up the CIL system and encourage more local authorities to adopt CIL. The best part is the recognition that where the land value uplift created by planning permission is particularly high, the CIL rates should be much higher.

My one note of caution here: CIL’s greatest strength is that it is fixed, which means it actually gets factored into land prices. Any moves to make CIL more flexible or responsive to market changes should be careful not to undermine that strength. Otherwise it risks falling into the same circularity as S106. This would mean a developer who bets on being able to haggle down their contribution can offer the landowner more. Having overpaid to win the site, they can then – legally – use the price they paid to show that any community contribution will not be viable.

We urgently need the NPPF rewrite to put to end this vicious circle, as promised. If the CIL reforms can avoid accidentally reinstating it, we could be on the verge of a more sensible and effective system for sharing the uplift in land value. That would give local communities more of the affordable housing and infrastructure they need. It would also give developers the greater certainty they need to grow.

Better sharing of land value uplift would be a big step towards building a greater number of more, higher-quality affordable homes. If the Letwin Review also moves to address the problems of speculation and excessive land prices, it could add up to the biggest land market reform in half a century. Now that would be truly exciting.

- To find out more about how land values shape our housing system, watch our New Civic Housebuilding video