What is a ‘desktop study’ and should they be banned?

Published: by John Bibby

Since the Grenfell Tower fire, the practice of using ‘desktop studies’ to sign-off cladding systems as fire safe has been the subject of significant controversy.

Despite the official review of building regulations calling for ‘significant restrictions’ on desktop studies and others calling for an absolute ban, the government has recently published proposals that could see them used more.

What is a desktop study?

Although building regulations have a reputation for being complex, some background is necessary to understand where a desktop study fits in.

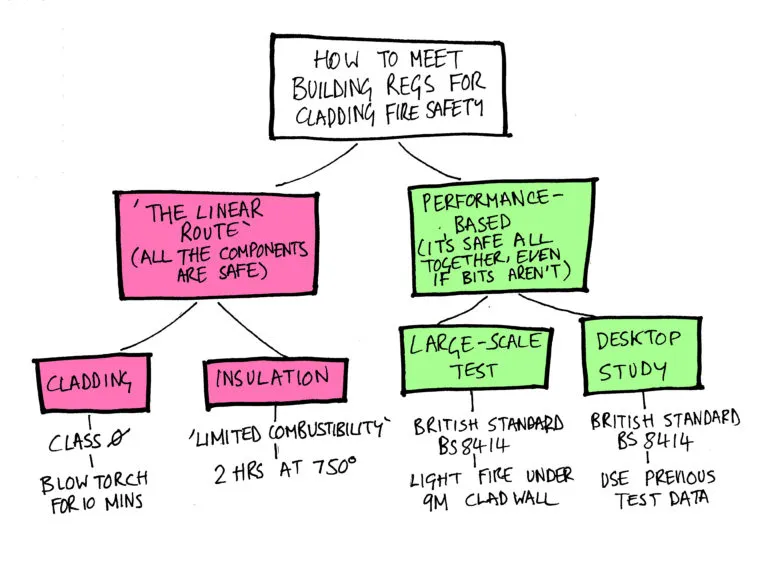

There are two main ways to be sure you’re meeting building regulations (see illustration above).[1]

The first is to use components (including cladding and insulation – see picture below[2]) that individually meet the necessary safety standards.[3] This is the clearest way and gets called the ‘linear route’.

The second way is to prove that all of the components are safe together as a whole system, even if individual components might not meet the linear route safety standards if they were tested on their own. The argument goes that within a system its possible for ‘unsafe’ materials to be protected by ‘safe’ materials.

For our purposes, I’m going to call this the ‘performance-based route.’

The large-scale test to prove that you meet the ‘performance-based route’ basically involves lighting a fire under a nine-meter-tall clad wall and seeing what the damage is after half an hour. It aims to replicate the conditions of a real fire. Large-scale tests are what the government commissioned last year after the Grenfell fire, and which found widespread use of unsafe cladding systems.

The current methodology for these tests is itself controversial and has been criticised by insurers for not being rigorous enough.

And this is where we come to desktop studies (officially called ‘assessments in lieu of a test’). The principle of a desktop study is to use data from these previous actual, real-life (controversial) large-scale tests, to extrapolate how a cladding/insulation system would perform if it were tested.

The materials themselves are never tested together. Instead, they get modelled in a spreadsheet.

You can think of it like this: a desktop study is like saying that ‘I don’t need to actually try a cheese and jam sandwich to know that I will like it’, because

a) I already know that I like cheese and;

b) that I like jam and;

c) that I like the combination of peanut butter and jam, and that’s kind of similar.

Therefore: cheese and jam has got to work, right?

The Hackitt Review and desktop studies

The sandwich comparison above may sound a bit over the top, but Dame Judith Hackitt’s interim report of her review paints a picture that looks appallingly slapdash.

She found widespread concerns with desktop studies, the quality of the data they’re based on, the rigour of the modelling, and the qualifications of who conducts them.

As Inside Housing has frequently reported, the consequence of all this is that at least one cladding system that was given a clean bill of health by a desktop study was subsequently proven unsafe when it was actually set alight.

As such, even though her full report is not due to report before the end of the spring, Hackitt has already recommended that the government ‘significantly restrict the use of desktop studies’.

The argument for a ban

In response to this recommendation, the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), Local Government Association (LGA) and more than 50 MPs have called for an out-and-out ban on desktop studies.

The argument for a ban is that it is the most robust and the clearest way to establish what materials are safe to use and meet building regulations. Polling has also found that more than 70% of the population support a ban.

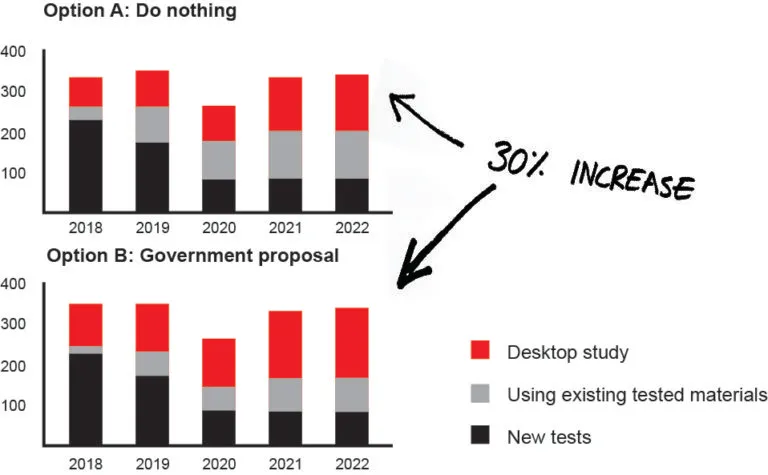

However, the government published their proposed response to Hackitt’s recommendation at the beginning of this month and doesn’t currently support a ban.[4] In fact, the proposal the government is consulting on would see more desktop studies being used, not fewer.

Confused?

Well, the government argues that desktop studies are a ‘proportionate’ way of figuring out whether materials are safe and have the benefit of allowing for more building product innovation.

The reasoning goes that if you have a cheap way to introduce new materials, the barriers are low. Conversely, if every time you want to try something new you have to do expensive, arduous testing, then you might try fewer new things. Therefore, they believe that desktop studies need to be kept.

The government believes that Hackitt’s concerns about the current shortcomings of desktop studies can be addressed by improving desktop studies with new standards. This is how they have interpreted the phrase ‘significantly restrict.’

Basically, instead of reducing the use of combustible components or relying more on real-life, robust, large-scale testing, the argument goes that what we need is better spreadsheets.

And this, the government also believes, will lead to them being used more. The consultation projects that increased industry confidence will lead to a 30% increase in the use of desktop studies over the coming years.

30% increase: the government’s projections of the use of desktop studies after new standards are introduced

Who is right about banning desktop studies?

The trade-off of low barriers to product innovation is less clarity about what materials are safe to use and less robust scrutiny of new products.

As a comparison, you could remove the rigorous requirements for testing and licensing new drugs to allow for more innovation in the pharmaceutical industry, but it would also put people at serious risk of taking something toxic.

After Grenfell, it’s also clear that our system of building regulations needs a complete overhaul and that the safety of residents needs to be made the highest priority. In light of all this, and without any clear evidence from government of what the cost of ‘reduced innovation’ would actually be, it is clear to us that those calling for desktop studies to be banned are right.

The question of banning desktop studies concerns future building regulations, and making sure a disaster like Grenfell never happens again. But there are still hundreds of tower blocks that are clad in unsafe materials that don’t even meet the current regulations.

Join our campaign, and sign our petition to get the cladding removed and replaced.

[1] This is purposefully a simplification. Find me on Twitter if you have any comments on any way you think this could be improved.

[2] For info: this is what unsafe aluminium composite material (ACM) cladding looks like. It’s plastic sandwiched between two sheets of aluminium.

[3] There is a complex controversy about what those safety standards are, which will be resolved by the Grenfell Public Inquiry. You can read more about the controversy in Inside Housing’s excellent Paper Trail investigation

[4] The consultation was published on 11 April and closes on 25 May 2018. While, officially, the government says it is consulting on banning desktop studies, this isn’t a modelled option in their consultation.

Photo credit: By ChiralJon (Grenfell Tower) [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)\], via Wikimedia Commons