Grey renting: the rising tide of older private tenants

Published: by John Bibby

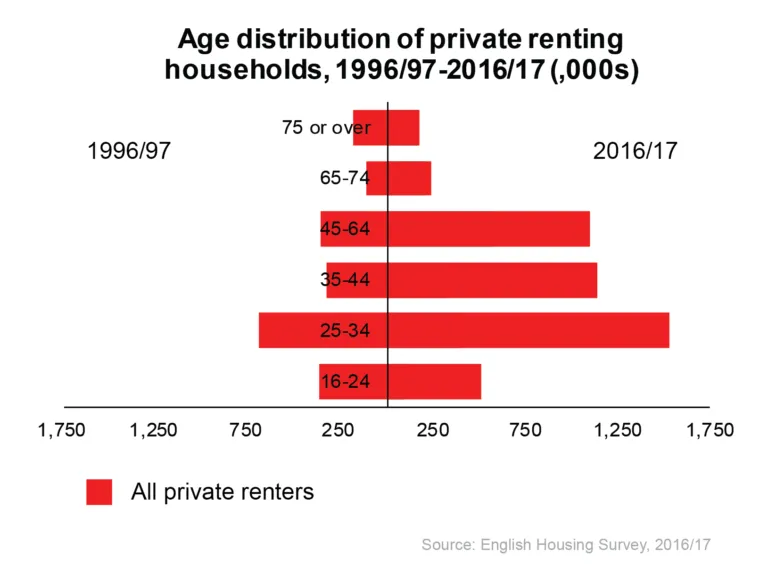

The number of private renters has skyrocketed over the last 20 years. In total it’s more than doubled, from just over 2 million private renting households in 1996/97 to almost 4.7 million in 2016/17.

This growth hasn’t been uniform across the age groups, though. It’s been much slower amongst older renters, with households headed by someone aged 65+ growing by only 40% compared to 144% amongst younger households.

However, new statistics from the most recent edition of the government’s English Housing Survey suggest a big tide of older private tenants is fast approaching.

If it’s realised, this shift in the way older people are housed could see increasing numbers of pensioners paying unaffordable levels of rent, forced to move against their will or made homeless.

The tide approaching

Predicting future tenure trends is a very complex business, and for the sake of this blog we’ll just look at a couple of simple scenarios. But, the indications are clear that, left unchecked, the number of ‘grey private renters’ stands to grow considerably.

You can see the tide of older renters coming from a distance, and it’s made up of households who are renting in their middle age today. There are now more than three times the number of middle-aged private renters, aged 45-64, than there were in 1996/97.

If over the next 20 years they were all simply to roll over into the 65+ age group it would add a vast 1.1 million older renting households, taking the number to 266% the current total.

Of course, it won’t happen exactly like that. Some of the current 45-64 cohort will buy or move into social housing over the next 20 years, as will some of the current over 65s. Being brutally honest, many of the private tenants currently aged more than 65 will die over the period.

But it won’t all be one-way traffic out of private renting either. New older private renters will get added too, for example due to relationship breakdown and divorce.

So, it is difficult to predict exactly how many of today’s middle-aged tenants will stay in the tenure into old age. But stats on middle-aged private renters’ prospects of buying give us a (very conservative) indication of the minimum number who are likely to stay renting.

With the scarcity of social housing and declining number of social lettings, buying a home is the only hope many middle-aged private renters have of not growing old in the tenure.

The English Housing Survey includes stats on the number of middle aged households who ‘don’t expect to buy’. If only this group were to stay private renting, and entirely replace all the existing older renters (i.e. if everyone 65+ now were to die or buy), it would still mean a 39% increase in older private renters.

The picture gets even bleaker when looking at ability to buy rather than just ‘expectations’.

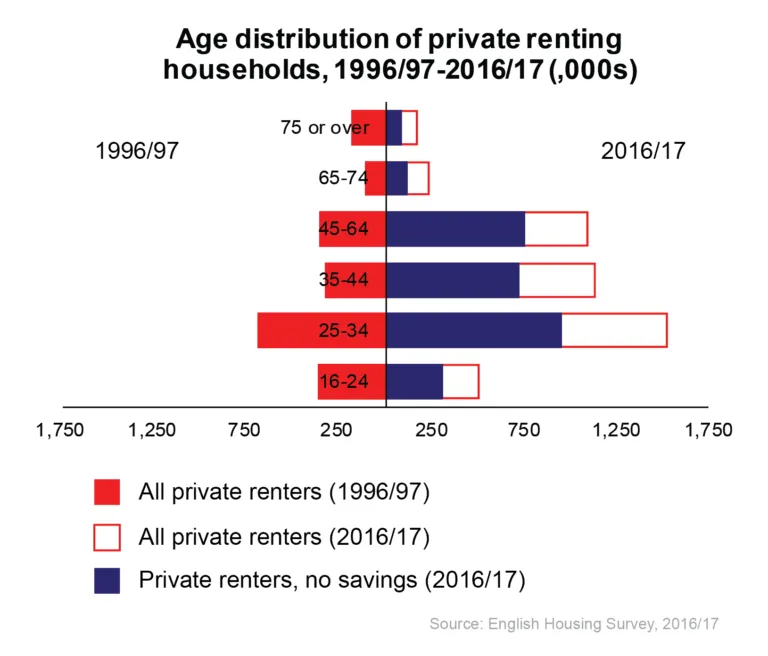

The days of being able to get a mortgage without a deposit are pretty much gone. So, even if they ‘expect’ to be able to buy, private tenants with no or limited savings are unlikely to be able to do it, unless they get a windfall like an inheritance.

755,000 of today’s middle-aged renting households have no savings at all.

If they were to entirely replace the existing 65+ cohort, it would equate to an 82% increase in older private tenants.

A further 163,000 have less than £16k in savings, substantially less than the current average deposit. Adding them in would see the number of older private tenants more than double (+122%).

The problem with the rise of grey renting

This coming increase in private renting into old age isn’t a benign change.

It is likely to mean more people struggling to make ends meet as they grow old.

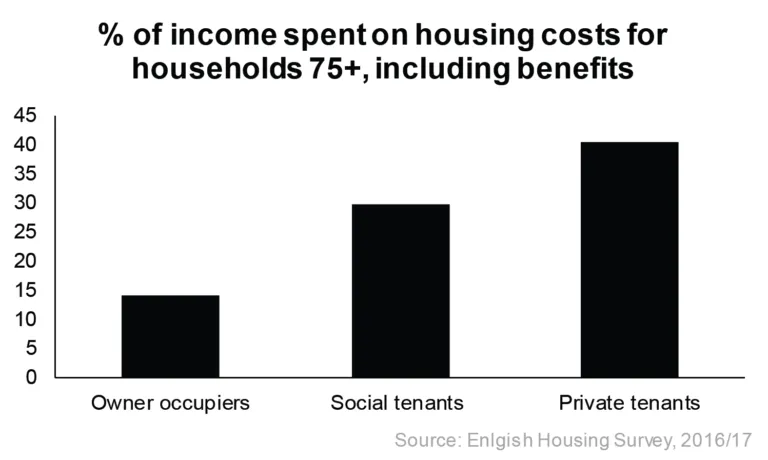

Older private renters pay by far the biggest amount of their income on their housing costs compared to their counterparts living in other tenures, and the effect is particularly stark for those aged 75 and above.

On average, these private tenants pay more than 40% of their household income on the rent, compared to less than 30% for social renters aged 75+. Older owner occupiers – most of whom will be living mortgage-free – spend just 14% of their household income on their housing costs.

These figures don’t include basics like energy costs, so spending more on rent directly eats into the amount that’s left for heating and other essentials.

Older private tenants are also much more likely to be forced to move than other private tenants.

Many younger private tenants move home to find work or to move in with a partner. But as renters get older, they increasingly tend not to move unless they’re served notice by their landlord.

For older private tenants, being forced to move by being served notice is the biggest single reason for moving. Almost 30% of private renting households aged 65-74 who moved did it for this reason in 2016/17.

This is a particular problem because it is incredibly easy to serve notice and force a tenant to move under England’s private renting laws. Unless these laws are changed, the increase in older private renters is likely to mean more pensioners forced to make disruptive moves against their will.

We’re worried that the combination of the high cost of renting in old age and the insecurity are already combining to help drive the increase in pensioner homelessness. The number of people aged over 60 and accepted as homeless has increased by 40% in just the last five years.

Without significant reform, the rise of grey private renting could make this even worse.

Solutions

Major changes are needed to make sure the downsides of private renting don’t blight old age for a growing number of people.

In the immediate term, the government’s announcement to consult on longer tenancies could go a long way guaranteeing older people a more secure home they know they’ll be able to keep for the long term. If you haven’t already, you can respond to the consultation to make this message clear to the government.

But over the longer-term, we have to reverse the downward spiral of social lettings by building more social rented homes too. For the growing number of older people who aren’t be able to buy, social housing is the best way to guarantee them decent and secure home at a price they can afford.