Permitted development: At what cost for the delivery of well-sized and genuinely affordable housing?

Published: by Cecil Sagoe

Last week, The Guardian ran a piece on a controversial conversion of offices into flats through permitted development rights (PDR). This article highlighted significant concerns about the tiny and sub-standard homes that are arising from the permitted development system.

Another issue, which we have previously flagged, relates to the non-existent contributions that these conversions are making to delivering genuinely affordable housing in England.

With flats as small as 13 square metres being created out of old office blocks, where we are being robbed of contributions to genuinely affordable housing, PDR is lowering the bar for homes in England.

Here, we take a look at how and why this is the case.

What are permitted development rights?

Conventionally, bodies wishing to carry out a development are required to submit a planning application and gain full planning permission from a local planning authority before they can commence with the development.

However, PDR allow certain classes of development to bypass full local planning. This means that there are certain types of development which will be automatically granted with planning permission by government. This deregulated system of development, for instance, covers extensions to existing houses and changes between different industrial and residential uses.

The controversy of office-to-residential conversions

One type of permitted development has drawn particular ire from people and organisations concerned with the supply of good quality, spacious and genuinely affordable housing.

This is office-to-residential conversions.

In May 2013, office-to-residential conversions were granted temporary PDR. A review by government in 2015 led to these conversions being granted with permanent PDR in 2016.

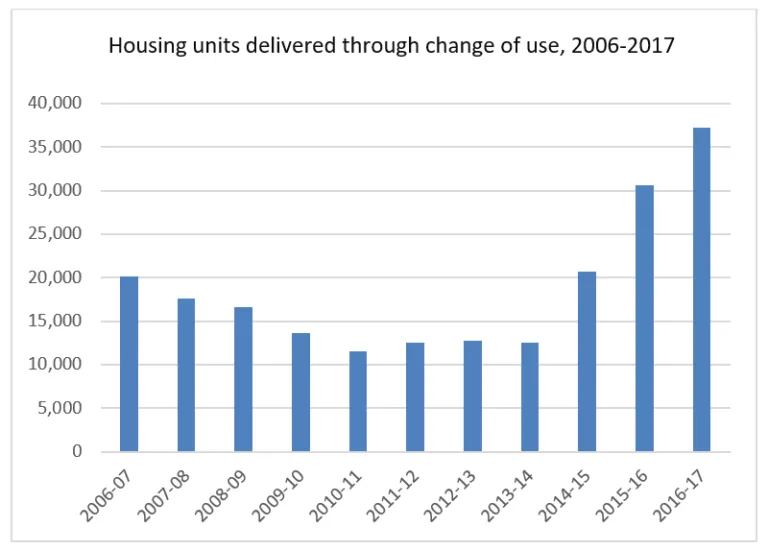

Government emphasised that these decisions would boost housing supply. Over the last two years these conversions have supplied more than 30,000 homes. But, it is unclear how much of this supply directly results from assigning office-to-residential conversions with PDR.

Historical statistics on overall conversions (inclusive of office-to-residential conversions) suggests that a reasonable proportion of these 30,000+ homes may still have been delivered in the absence of PDR for office-to-residential conversions. [1]

But, these conversions have been assigned with PDR, meaning they only need to be given prior approval by local planning authorities; and authorities can only consider extremely limited factors as part of the prior approval process.

Local planning authorities cannot enter into section 106 agreements with developers who are carrying out office-to-residential conversions through PDR. Crucially, this means that planning authorities can no longer impose affordable housing obligations on these conversions. Additionally, planning authorities cannot impose space standards on these conversions.

The inability to impose these planning obligations and standards is shocking given the dire need for good quality social housing in England. In a context where many of these conversions may have come forward even if they were not assigned with PDR, this begs a key question.

At what costs to housing quality and affordability are government currently willing to see housing developed?

Concerns with housing quality and affordable housing contributions

Last week’s Guardian article partially tackled this question by highlighting that permitted development is leading to the production of whole apartments that are sometimes smaller than a standard bedroom.

However, recent reports for the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) have more comprehensively addressed this question. One report indicated that although there were some good conversions across the five local authority areas studied—Camden, Croydon, Leeds, Leicester, and Reading—there were serious issues with overcrowding, health and safety (in particular fire safety) in many schemes.

Another RICS report demonstrated concerning implications for affordable housing delivery of extending PDR to office-to-residential conversions. It estimated that:

‘Local planning authorities across England have missed out on financial contributions with a Net Present Value in 2010 of between £37m (lower estimate) and £48m (higher estimate) between 2013 and 2017.’

Additionally, the Local Government Association estimated:

‘that the office-to-residential PDR has led to the potential loss of 7,644 affordable homes over the past two years.’

These are especially difficult losses to take given that the RICS reports have simultaneously indicated that conversions are highly profitable for landowners and developers, suggesting that these schemes could easily have provided a proportion of affordable housing.

The high profitability for landowners arises from the huge uplift in land values that they derive when prior approval has been given to an office-to-residential conversion. For developers, the profitability of a conversion is enhanced by their ability to cut on space standards and let or sell all of their properties at sky-high local market rates.

The end result is that these conversions are producing housing that is completely out of the reach of low-income groups who need a genuinely affordable place to call home.

We can do better

These are prices that we should not be willing to pay, and do not need to pay, in efforts to address the housing crisis.

Let’s be clear, we are not against office-to-residential conversions per se. We think they can be decent schemes as long as they go through full planning approval and deliver decent, safe and genuinely affordable housing.

Notably, in Scotland office-to-residential conversions must still go through full planning permission. As one RICS report has demonstrated in its focus on Glasgow, this policy landscape has not inhibited more office-to-residential schemes coming forward. The research identified that in Glasgow between 2009 and 2013 (prior to office-to-residential being given PDR in England) there were 40 full planning applications for office-to-residential conversions. From 2013 to 2017, there were 77 full planning applications for this type of conversion.

The report also emphasised that amongst the Glasgow schemes that have come forward 96% comply with national space standards. Furthermore, as they have gone through full planning processes they will have included agreements containing affordable housing contributions.

This illustrates that it is still entirely possible for a reasonable supply of office-to-residential conversions to come forward without foregoing housing quality or affordability concerns.

It remains important to continually remind government of this.

We must do better and make a strong case that under full planning office-to-residential conversions can be an important source of some of the good quality, well-sized, safe and genuinely affordable housing that we desperately need.

[1]Data drawn from MHCLG lives tables on housing supply, table 120. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/live-tables-on-net-supply-of-housing