The cap is scrapped! Where next for council housebuilding?

Published: by Rose Grayston

Last year, Theresa May used her speech at Conservative Party Conference to announce £2bn of new grant funding – the first money made available for building social homes since 2010.

Two weeks ago, the prime minister used a speech at the National Housing Federation’s annual summit to announce another £2bn of long-term funding for housing associations. At the time, we asked ‘Is Theresa May getting serious about social housing?’, taking stock of the many small actions May’s governments have taken to end years of outright hostility towards social homes, and to enable some social homes to be built.

But it was impossible to conclude that the prime minister was really getting serious, or really living up to her ambition to make fixing the housing crisis her top domestic priority. The changes her government had actually made were small, piecemeal, and entirely out of step with the sheer scale of the crisis we face.

Then the prime minister dropped a bombshell. On Wednesday, Theresa May again used her conference speech to make a housing policy announcement. But this time it was a big one: an end to the cap on council borrowing for housebuilding. This is currently the single biggest barrier to councils that build homes delivering more of them. By removing the cap, the government is letting councils back onto the playing field.

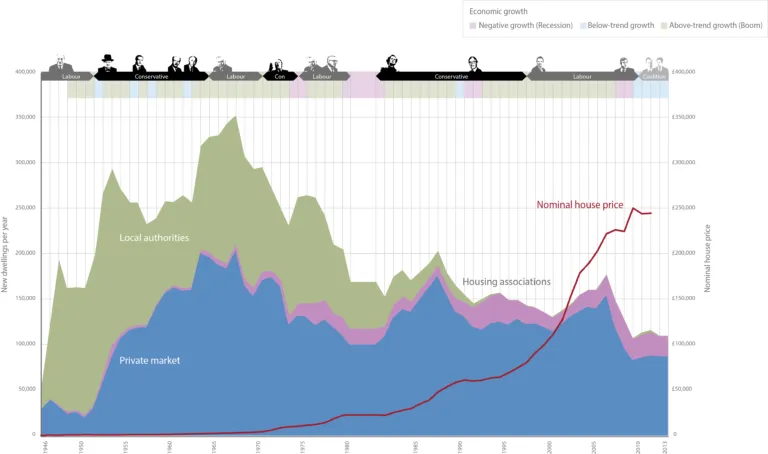

We don’t yet know the specifics, but this could be a big step forward for social housing, for more home-building overall and for the beginnings of a serious solution to our housing crisis. As the prime minister recognised in her speech, the country has never got close to building the 300,000 homes a year her government targets without local authorities as major players.

Success from the efforts of many

Scrapping the cap on council borrowing for housebuilding has been one of the housing sector’s key demands ever since the cap was introduced in 2012. Some have spent decades arguing for councils to have this kind of independence over their borrowing. The Local Government Association and the Chartered Institute for Housing have been at the forefront of the campaign, and Shelter has been proud to march alongside them with a host of other charities and campaigning organisations.

Along with the housing sector, individual Lords, MPs and councillors from the Conservative, Labour and Liberal Democrat parties have tirelessly banged the drum for liberating councils to borrow to build desperately needed homes. We are especially thankful to Lord John Horam and Lord Gary Porter, whose expertise and arguments have been invaluable for convincing the government that council housebuilding is worth investing in.

What’s changing?

Since April 2012, the self-financing settlement for council housing has allowed local authorities to undertake prudential borrowing – so long as they can comfortably service the debt, they can borrow to invest in housing. In theory, this opened the door to a renewal of council housing development. But the Coalition government then immediately introduced a cap on each council’s borrowing, which has been a financial straightjacket on council housebuilding ever since.

Work for Shelter by Capital Economics argued the borrowing caps were ‘arbitrary, distorting and counter-productive’. Some councils that desperately needed more housing had no or limited headroom, while others had significant headroom and but far less housing need to meet. Around half of all councils were allowed to borrow only £10 million or less – enough to build 80 or 90 homes. Some councils with pressing needs had no borrowing headroom at all, including Greenwich (with 11,000 on their social housing waiting list), Dudley (6,000), Exeter and Harrow (4,000 each).

Our research found raising the caps in 2014 would have delivered at least £7 billion of extra investment in social housing over the course of a parliament, or 10,000 new social homes each year. If councils had borrowed up to prudential limits, this could have increased to £19.7 billion over the course of a parliament, funding up to 27,500 additional social homes a year.

What does this mean for social homes?

With no borrowing cap, more councils will now be able to build on their own land. They’ll be able to use more of their Right to Buy receipts and commuted sums, which can be combined with borrowing to build social homes rather than sitting unspent in Treasury or council coffers. They’ll have the means to take advantage of their strong position to borrow – with ultra-low borrowing costs and many underleveraged assets – to bring forward housing schemes that no one else could.

But there will be no overnight results. While some councils that are already building will be in a good position to borrow and scale up their housing programmes, others will be starting from scratch. It will take time for councils to build up the capacity to deliver homes at scale again. And while scrapping the cap removes an important central government barrier for councils to build the social rent homes we really need, there are still many to overcome:

Definition of affordable housing

As we’ve blogged about many times before, the definition of “affordable housing” has been weakened to the point of incoherence. There is no guarantee that councils will use their new freedom to borrow to build the social rent homes we really need – although they have strong financial incentives to do so, to reduce the costs of homelessness and temporary accommodation. Other barriers mean even councils committed to delivering social homes will have a hard time doing so, though.

Land

Scrapping the borrowing cap makes land reform even more important. For councils not already building, the biggest barrier they face is access to land. If councils have to bid for land against private developers under our broken land laws, the higher prices they’ll pay will force them to build less affordable or worse quality homes to recoup their money. This would be a tragic missed opportunity, with borrowing for social homes diverted into an already bloated land market. The government must reform the Land Compensation Act 1961 to guarantee a supply of affordable land for affordable homes.

Right to Buy

The government will need to look seriously at Right to Buy. It’s difficult or impossible for councils to make the finances of building social rent homes stack up under Right to Buy, as they might need to sell the homes at a large discount and hand over some or all of the remaining sales receipts to the Treasury in fairly short order. It’s like running a bath with the plug out.

At a minimum, the government should allow councils to keep Right to Buy receipts and to exercise more control over how the policy works locally, so homes sold can be replaced. The current consultation on reforming the rules around Right to Buy receipts is an opportunity to push for some of these changes.

Grant levels

While some grant has been made available for social rent, the money available per home covers a historically low share of building costs, and the number of grants is still pitifully low compared to housing need. The less grant councils have to build homes, the more they must borrow for each home. This then pushes rents up and means that rental income is needed for repaying lenders, leaving less for repairs, maintenance, improvements and other things tenants might want. We can’t build social homes on borrowing alone.

There is a lot more work to do at every level of government to deliver the revolution is social housebuilding we need. But there can be little doubt about it now: yes, the prime minister is starting to get serious about social housing.