In the coming months, the government is due to report the results of its consultation on longer private tenancies. It will be our first chance to see whether the government will stick to its guns and change the law, so that all private renters get a longer tenancy and genuine security from no-fault ‘Section 21’ evictions.

In this post we’ll consider what will happen if the government loses its nerve by opting for a non-legislative, voluntary approach. If it does, low income tenants on housing benefit would lose out most. Although these renters arguably need protection the most, ‘no DSS’ discrimination means that almost 90% of landlords would be unlikely to give them a longer tenancy unless they’re required to by law.

The government’s longer tenancies consultation

A lot has happened since summer, so a quick recap on where the consultation stands is in order.

In July, the government sought views on a new three-year tenancy. During the tenancy renters would be protected from no-fault eviction but would be able to move out by giving notice.

It is not the permanent protection that renters need (and currently get in Scotland), but it would be a step in the right direction.

Crucially, though, government proposed three options for implementation:

- Legal change – so that every renter would be guaranteed a longer tenancy as a legal minimum. This is how permanent tenancies are implemented in Scotland and what renters commonly get in Europe and parts of America

- A new tax incentive – so that landlords would get a cash bung for voluntarily opting to give their tenants a longer tenancy. We can’t find any international precedent for this

- Promoting voluntary take-up – the weakest option, leaving both the law and financial incentives untouched. Basically, continues existing approach

Low income renters would miss out more under a voluntary system

With no international examples of tax incentives and previous attempts at promotion having failed miserably, it’s unlikely that a voluntary approach to implementation would lead to a significant increase in the use of longer tenancies. But even if it succeeded on its own terms, English private renting sector would get stratified into an unfair, two-tier system.

This is because any kind of voluntary implementation is only ever going to be partial. For example, 46% of landlords say they would be likely to offer a longer tenancy if they got a tax break. Even if all those did, the other 54% would still be left operating on current six or 12 month tenancies.

The market would be split in two, with almost half blessed and on a longer tenancy, and the rest still struggling with an insecure, short contract.

This would be unfair on its own. But our new analysis shows that it would also be regressive.

Existing discrimination against low income renters, particularly those on housing benefit, would mean they would be much more likely be the ones missing out on a longer tenancy. This includes a huge number who are in work on low pay. 44% of working age private renters on housing benefit are already in work.[I]

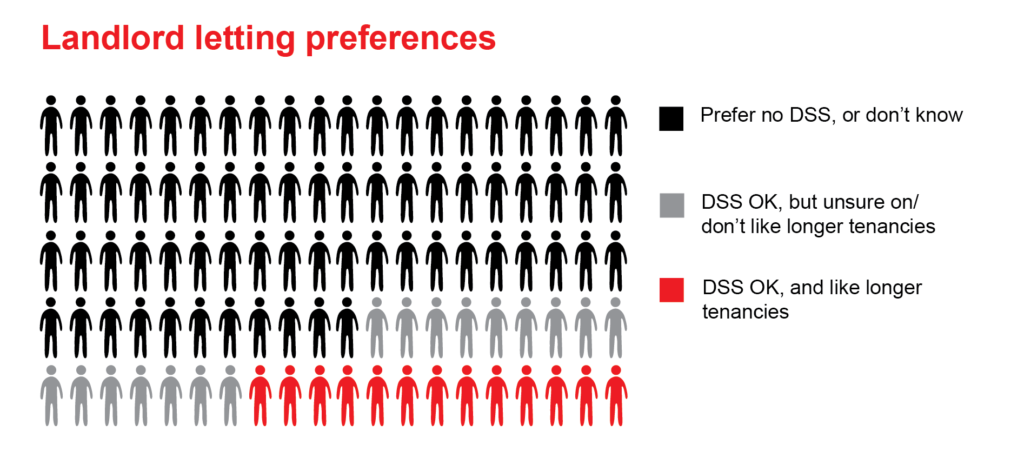

Survey data from YouGov shows that only 13% of landlords both like the idea of longer tenancies and don’t discriminate against people on housing benefit. An overwhelming 87% have attitudes suggesting a tenant on housing benefit would struggle to get a longer tenancy from them.

With at least 22% of private renters receiving housing benefit, there’s a clear mismatch with the number of favourable landlords.

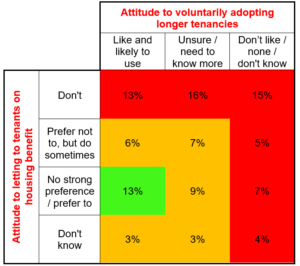

Table: detailed breakdown of intersecting landlord preferences

Source: Views on longer tenancies and HB are from YouGov survey of 1137 UK private landlords (results based on 993 letting homes in England or Wales), online, 18+, July-August 2017

We’ve only considered the overlap between those landlords who (A) like longer tenancies and (B) don’t discriminate against tenants on housing benefit. We don’t know about attitudes to the combination of the two, i.e. how many would give a longer tenancy to someone on housing benefit. Some might be willing to do one or the other, but not both.

There is only one way to avoid such a regressive, two-tier system. It’s by changing the law to give private renters a longer tenancy as a minimum.

Such a change would create a new, higher, level playing field for all landlords as well as renters. It’s a standard of private rented housing that people in most of our neighbouring countries already enjoy, including those living on low incomes. Their experience shows us that it’s perfectly achievable.

In the coming weeks, the government has the opportunity to move towards introducing longer tenancies through a legal change and improve life for millions of low income renters. They must take it.

[i] DWP, Stat-Xplore; 44.3% of private renters on housing benefit under 65 were employed as of August 2018