Benefit cap: ‘undoubtedly harsh’ yet not unlawfully discriminatory

Published: by Steph Kleynhans

Today, the Supreme Court has acknowledged that the household benefit cap is not achieving its stated aims and is inflicting poverty on people. However, the judges also declared (by a majority of 5-2) that the cap does not unlawfully discriminate against lone parents or breach the rights of their children.

The appeal this stems from was brought after the High Court found in 2017 that the cap unlawfully discriminated against lone parents with children under two – a decision that was later overturned by the Court of Appeal. In the Supreme Court, the government successfully argued that they could pass the legal test to provide justification for a policy that discriminates – in this case against lone parents and children. Shelter intervened to illustrate that it’s virtually impossible for families to move home to escape the cap, meaning they instead face homelessness and destitution.

While the latest result is disastrous for many families hit by this punitive policy, the Supreme Court’s judgment highlights some critical failings of the benefit cap:

- there are ‘sound reasons to accept’ that the cap is inflicting poverty

- there is no clear evidence that the cap has achieved the government’s intended aims

- the lowering of the cap in 2016 was without sound basis

Later this year, the government will be publish its own evaluation of the lowered benefit cap alongside independent analysis from the Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS). We urge that the points raised by the judgment today, on how the cap inflicts poverty and is failing its aims, should be carefully considered during the evaluation.

The benefit cap is inflicting poverty on mothers and children

When the benefit cap was introduced, it was set at £26,000 per year. This was reduced and the amount of total benefit payments a household can now receive is £20,000, except if you live in London, where it’s £23,000.

In today’s judgment, Lord Wilson observes that there are ‘sound reasons for accepting the evidence that the effect of the benefit cap is to reduce a family well below the poverty line’. Shelter has consistently highlighted the destitution caused by the cap. As part of our evidence in this case, we drew attention to examples of mothers who have gone without food to make sure there’s enough for their children, and of those who have had to stop paying for heating to save money for rent. These are decisions no mother in Britain should have to make.

At the end of last year, we published a blog in response to the then Minster’s top tips for avoiding the cap. These were to move, to work for more than 16 hours a week, to negotiate cheaper rent or to take in a lodger – all of which are incredibly difficult if not impossible for lone parents with young children. This judgement further highlights the trap for lone parents trying to simultaneously find work and affordable childcare, or who are trying to find a cheaper home to move to.

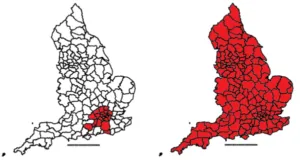

Our research demonstrates that a single parent family with three children, for example, could not move to a cheaper area or home to avoid the cap, because every area in England is now affected by the cap. Housing benefit claimants already face numerous barriers in finding a private rental home, so finding a landlord willing to take much lower rent is unrealistic.

Previous cap of £26,000 in England vs. present cap of £23,000/£20,000

The cap is not fulfilling the government’s intended aims

Originally, the government argued that lowering the benefit cap would save up to £430 million over four years in cash terms. Today’s judgment points out that these figures do not consider any operational costs, nor the cost of the additional support, such as Discretionary Housing Payments (DHPs), to mitigate the cap’s effects.

The President of the Supreme Court, Lady Hale, described the savings as ‘very small’, while Lord Wilson makes the important point that the government has ‘scarcely been pressed’ to answer for the lack of savings. The IFS’s independent analysis later this year needs to thoroughly address this and ensure the government is held accountable.

The lowered cap is arbitrarily low

The original cap of £26,000 was ‘determined by the estimated average net earnings of a working household’. However, Lord Wilson describes the lowered cap as, essentially, arbitrary: ‘Clearly the yardstick of average net earnings of a working household was abandoned – otherwise the figures would not have come down.’ He found the £23,000/£20,000 cap does not provide ‘adjustment…for inflation’ and, by that measure, has already lost 5% of its real value, ultimately driving more people into poverty.

Mounting pressure on government to drop their benefit cap policy

This is not the result the families we work with had hoped for. It leaves a situation where a government policy is accepted to cause poverty and hardship, and yet can survive the legal test around justification. However, there is a lot to take away from today’s decision, which follows a damning report in March by the Work and Pensions’ Committee that stated that the cap ‘leaves people without enough money to meet their basic needs’. This plus today’s judgment create further pressure on the government to abolish a policy dubbed ‘undoubtedly harsh’ by the Supreme Court.

If the government is serious about preventing homelessness**, it must abolish this damaging policy.**