Successful housing markets are built on social homes

Published: by Rose Grayston

It’s obvious that there is no solution to our housing emergency that doesn’t include many more social homes. Homes with secure tenancies and genuinely affordable rents pegged to local incomes, with enough space for children to play and do homework, and for adults to live with dignity. On its own, market housing – that is private housing for rent or sale – simply cannot provide a home for everyone who needs one without compromising standards in unacceptable ways.

100 years ago, the architects of the 1919 Addison Act – the legislation that first kicked off social housebuilding at scale – understood this. Faced with a housing shortage, slum conditions and rising discontent, the government of the day stepped up to the plate. If the market couldn’t provide decent housing for those on modest incomes, government would. In his guest blog celebrating this landmark Act, social historian John Boughton tells the story of how politicians a century ago refused to accept the conditions they saw at the bottom of the housing market.

But besides providing an alternative to poor-quality market housing, there is another, less well understood side to the role that social housing has played in this country’s history. It’s the same role we now desperately need it to play in our future: as the foundation of a successful housing market and construction sector. By building social homes, the new government can support construction skills and innovation. Far from being in conflict, social housing and market housing can support each other – and here’s how.

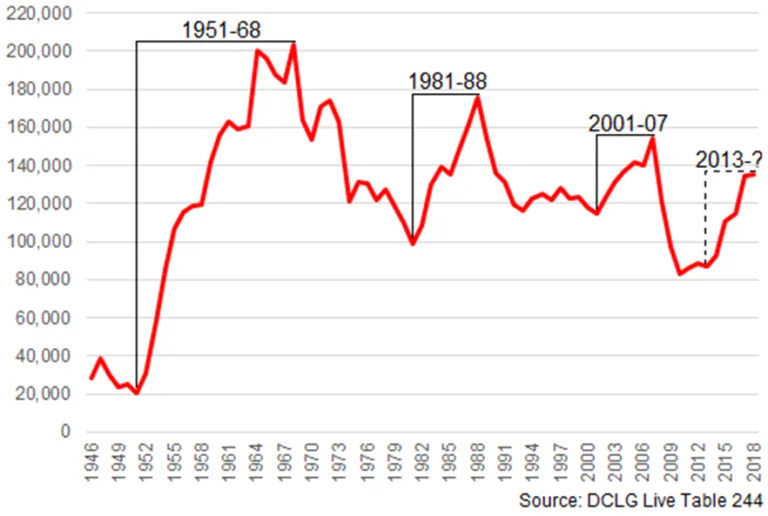

Ratcheting down: private housing starts, 1946–2018

In a housebuilding system reliant on only market housing, developers compete against each other to pay the most for land. To do this, they assume house prices will remain at current unaffordable highs. Having taken on a large upfront risk through high land costs, developers then need to recoup their investment. So, they tend to build for the top of local housing markets, building as slowly as necessary to maintain prices.

But when sales prices soften, even moderately, the numbers of new market homes (or housing ‘starts’) plummet. Developers have no incentive to keep building if they will have to sell homes for less than they assumed when buying land.

As housing starts plummet, so does the demand for skills and materials. In this situation, many construction workers simply leave the sector, never to return. It is no coincidence that construction workers are more likely to be self-employed than workers in any other sector. Why would housebuilders maintain a large permanent workforce, or invest in the skills of that workforce, when they know they will not have a steady stream of work?

Because it is hard to predict and plan for what you will need, the prices of materials like bricks have become more volatile. The last government’s independent review of build out rates found that brick shortages now represent a real limiting factor on our ability to build homes, as manufacturers tend to focus their energies on reliable clients. As the construction industry has adapted to manage the risks of cyclical demand, construction capacity has atrophied.

Similarly, the long-heralded shift to modern methods of construction (MMC) is still yet to materialise, because the short-term speculative nature of the industry makes the expense and risks of investment in innovation unattractive. Investors generally do not want to commit to factories which will be moth-balled at the first signs of the next housing market slowdown.

From stop-start to build-build

Compare this to a mixed housebuilding system building both market and social homes. When governments fund and enable social housing at scale, homes can be built as fast as housing need demands and construction capacity allows. As the Farmer Review of the UK Construction Labour Model found in 2016, a major programme of social housing supports predictability of demand for labour, skills and materials, resulting in a less risky operating environment for housebuilders, developers and planners. In other words, the booms and busts of cyclical market supply are smoothed out by counter-cyclical social supply, so capacity can be maintained and increased despite housing market cycles.

Innovation and new technologies have also thrived on this certainty, creating new opportunities to expand development capacity. It is no coincidence that the last time that MMC made a major contribution to overall housing supply was when councils were commissioning large numbers of social rent homes.

Of course, the benefits of a more sustainable skills base and of innovation in construction would be felt far beyond the developments which first enabled them. If social housing schemes keep construction workers in the sector during market downturns, those experienced workers will still be available to the private sector when the market recovers. If social housing schemes provide enough stable demand to keep MMC providers in business, market housing providers will be able to benefit from their services too.

While construction capacity is often cited as a barrier to building social housing at scale, in fact the counter-cyclical demand generated by a programme of social housing would support an expansion of capacity – and with it a significant number of well-paid trades jobs. As we celebrate what the Addison Act did a hundred years ago for communities in need of good homes, we should also remember and celebrate social housing’s historic role in making Britain’s housing market work harder and smarter.

Join 70,000 other supporters. Ask the new government to build a new generation of social housing by signing our petition.