With the new government publicly renewing their ambition to see more people owning their own home, we’re reviewing the main policy tool recent governments have used to try and achieve this.

Since 2013, Help to Buy has been the flagship housing policy to make ownership a reality for households dissatisfied with the private rental sector – the only alternative given the current level of social housing supply. Through it, government has funded around £12.5bn in equity loans, resulting in around 220,000 households getting the financial support to buy a home.

The devil’s in the detail

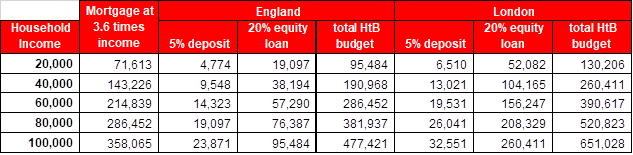

Firstly, the details. Help to Buy is a government loan to households towards the purchase of a newly built home. It provides up to 20% of the value of the property – or 40% in the more expensive London area – if a buyer can get together at least 5% for a deposit themselves.[1] The table below shows what this means for different levels of incomes, both for England and London. Notice that bigger incomes help in accessing larger equity loans.

Table 1: Estimated homebuyer budgets (£) using Help to Buy

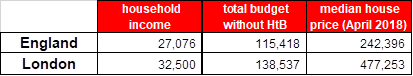

For clarity, the typical home purchase is made with a mortgage at around 3.6 times a buyers’ income, and the deposit paid is on average 16% of the purchase price[2]. Now, the average private renter household has an income of £27,000 before tax (or £32,500 in London), so it’s clear from the table below that getting onto the housing ladder is going to be challenging, even for those who are fortunate to have a deposit.

Table 2: Estimated homebuyer budgets (£) with Help to Buy

Policy in practice

With that in mind, I think it seems like most people would assume that Help to Buy is there to support those who really need it – i.e. lower income households. But the data says something very different.

Firstly, not all Help to Buy sales are to first time buyers. Since it started, only four of every five (81%) users have been trying to get on the property ladder; some people are being helped to move up the ladder. Secondly, the official evaluation of Help to Buy says that only two in five (41%) Help to Buyers actually needed the programme to get on the housing ladder. The majority used the programme to buy bigger and more expensive homes than they could otherwise have bought.[3]

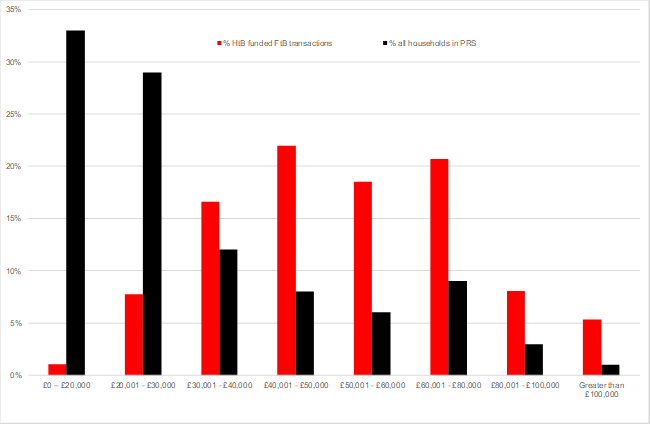

Not great! But wait; there’s more. If you look at the incomes of Help to Buy first time buyers compared with the incomes of households in the private rental sector (the source of most first time buyers[4]), it gets worse.

Chart 1: Percentages of Help to Buy beneficiaries and PRS households by income

In the latest year of Help to Buy, one in 20 of the first time buyers had household incomes of £100,000 or more. If you look at who’s in private renting right now, only one in 100 households earn that sort of money. In fact, most privately renting households have incomes of £40,000 or lower (73% to be precise), yet only a third of Help to Buy users earn the same. So, private renters on modest – some might say typical – incomes have about a one in 281 chance of using Help to Buy, while these unusually high earners are quite common.

The average first time buyer using Help to Buy earns £50,000, which is 85% more than the typical private renter household; in fact, only 19% of privately renting households earn that much.

So, why on earth is government spending money on people who don’t appear to need help? Well, the obvious answer is that house prices are now so high that it’s generally only wealthy people who can afford to buy. Meanwhile, developers are still building overpriced and often unappealing properties[5]. Help to Buy is doing nothing to challenge this situation, if fact it is sustaining a developer model of housebuilding that is not at all responsive to consumer demand.[6]

Help to Buy is appealing because most dream of owning their own home, but the programme really isn’t what we need right now. While government ties up billions in overpriced new builds, the lack of supply means the average private renter spends 41% of their take home pay on properties they probably don’t want to live in[7] and social housing remains at historically low levels.[8]

Government needs to ditch Help to Buy and focus on the policies that will solve the housing crisis, not sustain it. It’s why Shelter is calling on the government to instead focus on providing affordable, stable homes for those who really need help, by investing in social housing. Join us in calling on for the new government to invest in 3 million more social homes.

[1] Further details on the scheme can be found here.

[2] Based on analysis of mortgage statistics from the Bank of England

[3] The evaluation asked whether buyers could have afforded a property they wanted anyway; the same property they ended up buying; or a similar property on the second-hand market. Full info here.

[4] 70% of all movers to owner occupation come from the PRS. This rises to 73% if you account for Right to Buy movers.

[5] Poor quality and unappealing carbon copy developments have been identified as a problem, and government has launched a commission to see how this problem can be solved. Full info here.

[6] The Help to Buy evaluation confirms that one of the policy objectives of the programme was to help support the delivery of more homes.

[7] Based on head of the household and their partners take home pay plus any benefits; EHS 2017-18

[8] In the last three years, social housing supply has dropped to around 6,000 units annually, meanwhile there are over one million households on the social housing waiting list.