New builds? Don’t get me started

Published: by Alex McCallum

Last week saw the release of data on housebuilding, with some good news for once; a little over 214,000 new homes were built this year, and total supply – including conversions – is higher than it has been for decades; 241,000 in fact. Given government’s target is to reach 300,00 net additional dwellings annually by the middle of next decade; they and developers are celebrating.

But if you understand the housing market, you’ll be waiting for the fall – and here’s why.

Market dynamics

There are three important fundamentals to remember which help us understand how the housing market works:

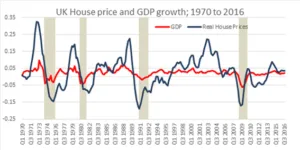

1. House prices are set by demand

The cost of building a home is not how the price is set. Prices are set by the demand for housing; how many people want a home of their own (or as an investment); and, more importantly, how much money they have available to buy it. The chart below shows this well, when recessions happen (highlighted in grey) house prices drop too. This means that when the economy is doing well and incomes are rising, house prices usually rise too. Demand has little to do with need however; your might be desperate for a home of your own but if you can’t afford it, your needs make little impact.

Source; ONS and Shelter analysis

2. Developers are after a profit

This is not a bad thing, but it does dictate developer behaviours. For example, since the mid-90s there have been around 930,000 housing transactions annually, new build homes represent a fraction of total market activity (10% on average). This means that developers can’t sell their homes for much more than prevailing market prices. Otherwise people will simply buy an existing home rather than a new one. Economists call this being a price taker – it means you can’t dictate the selling price. Developers make a profit by building when prices are right for them. If they build too many homes, they won’t be able to sell them unless they sell at a discount, damaging their profit.

3. Homes take a long time to build

Whether we like it or not, homes do take time to build, so when a developer starts a project, buys the land, contracts labourers, organises for materials to be delivered etc. there are substantial upfront costs that need to be covered when they sell. Above all, the way the land market works encourages developers to take a rosy view of future house prices to offer the best price to landowners. If house prices take a dive before a project finishes, developers are going to take a hit on profit.

So, developers are only going to build if they expect the final selling price to be enough to return a good profit[1], and they can look to economic forecasts to see how the economy is growing and whether incomes are going to allow people to buy their homes once they’re built.

Take a moment to let that sink in and ask yourself what you’d be doing now if you were a developer. Feeling positive about the future?

Confidence

We all know that right now in the UK there’s a lot of uncertainty. We could spend a lot of time discussing the whys, but as a slightly miserable summary: businesses are not feeling particularly confident; the economy is growing at a slow rate; and we may be edging towards recession[2]. Even though wages are rising faster than they have been for a while, incomes are still low, in comparison to where they were before the last recession.[3] House prices are not showing particularly strong growth either.[4]

Given these conditions, what might we expect developers to be doing? Let me show you what they have done previously.

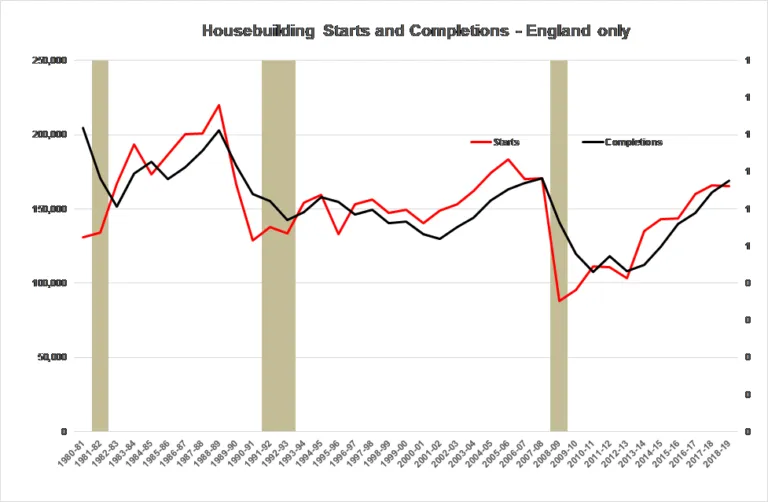

Source; MHCLG

At the turn of the century house prices began to rise, so developers began chasing the profit opportunity by starting new housing projects faster than they were completing them. In a fast-rising market this is no problem because any delays in completions are only going to result in a higher selling price later down the line and probably more profits – remember the costs of building are up front.

But we all know that the bubble burst in 2008, and big time. Developers responded by cancelling new projects, slowing supply, to avoid spending money that they might not get back when they eventually finished building. Overall starts dropped by half (48%) and if you strip out public sector building (which I’ll come back to in a moment) developers cut back by 55%, or 80,600 units, in a single year. Developers also rushed to finish off outstanding projects so that they could sell as quickly as possible to avoid further losses from falling prices.

A second glance

The most recent release on housing starts and completions, from MHCLG,[5] suggests that developers may again be managing their book of work to avoid potential losses in the near term. For the first time in six years starts are down on last year, albeit marginally so; similarly, the future of the Help to Buy scheme is uncertain. Help to Buy, as we’ve explained in the past, is a great way to help developers sell big, expensive homes, and not a very useful tool to alleviate the housing emergency.

Developers looking to maintain their profits will be reading the market in the same way we are, get in quick now before the market turns and losses become more likely.

Build better, build social

Supply is definitely needed to deal with the housing crisis, but it has to be the right kind of supply. Most renters cannot afford expensive new homes; we need sustainable levels of housebuilding and homes that are affordable to those who need them – not just the few who can currently afford them.

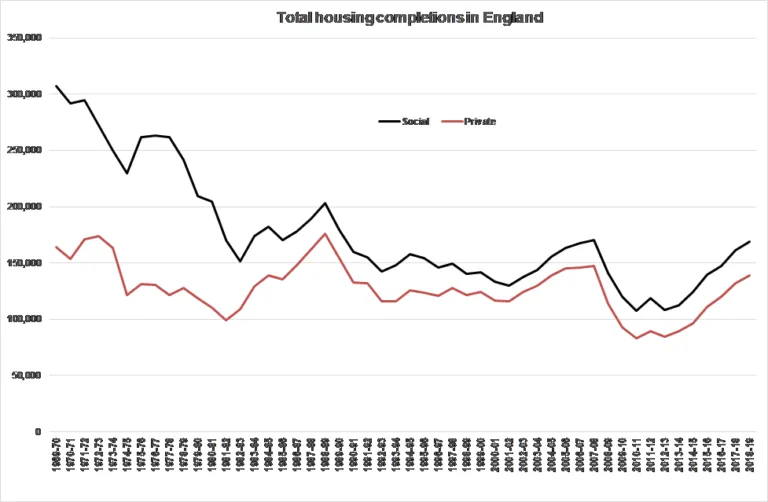

Source; MHCLG

It goes without saying the solution needed is more social housing. We cannot expect developers to solve the housing crisis when in actuality it is their model of delivery that has helped to create it. While the numbers look good right now, history shows us that the private sector (the red line above) has struggled to expand supply much over where it is now. Social housing demand is set by government (the black line) through its grant funding programmes, not by the economic conditions of the day.

That’s why Shelter will continue to call on the government of the day to commit to higher levels of public spending on social housing,

[1] And by good we mean 20%. That’s the industry standard and because the UK has a small number of very big developers (who are listed on the stock market) this level is set in stone.

[2] https://www.ft.com/content/3a6c470e-048c-11ea-9afa-d9e2401fa7ca

[3] ONS data on wages, adjusted to account for the effects of inflation, show that on average we still earn less as a nation than we did back in early 2008 – https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/articles/supplementaryanalysisofaverageweeklyearnings/september2018

[4] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-house-price-index-summary-september-2019/uk-house-price-index-summary-september-2019