New data makes the case for a new generation of social homes

Published: by Hannah Rich

Last week saw the release of the English Housing Survey (EHS) – the most comprehensive source we have for understanding the housing emergency. This government survey collects information about the quality, condition and affordability of the homes people live in. It’s been running for 50 years in various forms and is an invaluable record of how people’s housing circumstances have changed over time.

And yesterday new figures were released, which tell us how many households are on the waiting list for social housing in England.

Both data sets highlight the urgent need for a new generation of social homes.

Long-term decline in social housing

This was a common theme that came out of our social housing commission and it’s not a point we can overstate.

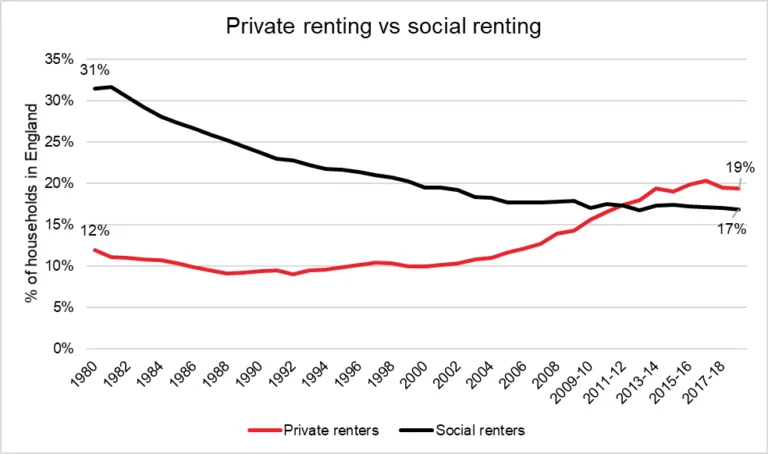

There has been a long-term decline in the number of households who live in a social home. Since 1980, the number of social renting households has declined by 26%. Over the same period, the number of households who live in a private home has more than doubled. 2012-13 was the first year that the percentage of private renters (18% of households) was greater than the percentage of social renters (17% of households).

Source: MHCLG, English Housing Survey 2018 to 2019: headline report, Annex Table 1.1

This is unsurprising in the current context: in 2018/19 only 6,287 new social rent homes were delivered. In the same time period, sales and demolitions of social housing totalled 23,740 homes. Assuming the homes lost were previously let at social rents, this is a net loss of at least 17,000 social homes in a single year – and this is even before we account for social rent homes converted to less affordable forms of renting [1].

While we continue to lose more of the homes that we need the most than we gain every year, is it any wonder that there are more than 1.15 million households on waiting lists for a social home?

More families live in the private rented sector

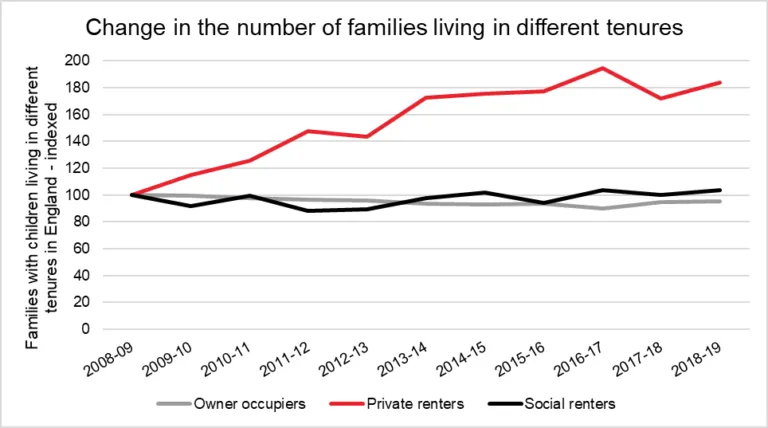

Although the total number of households living in the private rented sector (PRS) has remained relatively stable at just over 4.5 million households, the number of families living in a private rented home increased by 7% in the last year alone. The number of families living in the PRS has shown a largely upward trend over the last decade. In comparison, the number of families living in owner occupied and social renting households has been relatively stable.

Source: MHCLG, English Housing Survey 2018 to 2019: headline report, Annex Table 1.5

A quarter (24%) of all families in England now live in a private rented home. This is a problem because the PRS is more unaffordable than other types of housing, leading to people having to cut back on essentials and live in homes that do not meet their needs.

Private renting remains unaffordable

The PRS is widely understood to be the most unaffordable type of housing and this hasn’t changed. Households living in a private rented home spend on average 40% of their income on rent. This is more than social renters (30%) and owner occupiers (19%). The figures also show that average rents for private renters have increased by 13% in the last five years.

While rents have increased, housing benefit for private renters has been frozen since 2015. This results in private renters who receive housing benefit regularly being forced to make up shortfalls, where their housing benefit (or Local Housing Allowance (LHA)) does not cover their rents. Our research shows that for those on low income and low levels of savings, the average shortfall between LHA and rent is £113 per month.

For too many this leads to debt, poverty and homelessness. Our research shows that to keep up with rent, more than a third (36%) of private renters receiving housing benefit have cut back on food for themselves or their partner and 1 in 5 (21%) say either themselves or their partner have skipped meals [2].

This is why the government’s recent announcement to raise LHA in line with the Consumer Price Index (CPI) is not good enough. The government emphasised that people would receive on average an additional £10 per month. This isn’t going to help much for households with average monthly shortfalls over £100.

High levels of overcrowding

As a result of this unaffordability, many private renting households are being forced to live in overcrowded homes.

There are more than 283,000 households living in overcrowded privately rented homes. This has doubled (increased by 95%) in the last decade, compared with a 27% increase for social renting. We know that most of these households are families with children.

Although the number of social renting households affected (318,000) remains higher than households in the PRS, the gap between the two is narrowing.

Source: MHCLG, English Housing Survey 2018 to 2019: headline report, Annex Table 1.21

When the choice becomes so restricted, people are forced to live in homes that don’t meet their basic needs just to avoid homelessness. This is because they simply can’t afford anything else.

Homeownership is not the solution

The government continues to present homeownership as the solution to the housing emergency, largely through its continued investment in the flagship housing policy Help to Buy. The aim of this policy is to make ownership a reality for households who are unhappy with the private rental sector. However, as we’ve previously shown, Help to Buy doesn’t help those who really need it – lower income households.

The new figures reinforce this and show that homeownership remains out of reach for many. Although the number of owner occupiers has increased by 2% (234,000 households) in the last year, the number of recent first-time buyers has reduced by 7% over the same period. This means that there are 58,000 fewer first time buyers than the previous year. For those who are able to get on the housing ladder, they are more likely to be high earners with six in 10 (62%) first-time buyers being in the two highest incomes groups.

What are the solutions?

As both homeownership and social housing remain out of reach for many, we’ve seen an increase in the number of people forced to live in a private rented home. The PRS remains more unaffordable, forcing many households to cut back on essentials and live in homes that do not meet their needs.

Government must raise LHA so that it covers at least the cheapest third of private rents in the upcoming budget. This will ensure that it achieves its purpose: to enable people to actually afford their rent. To provide the stable, genuinely affordable homes that families truly need, the government also needs to build a new generation of social homes.

Sign our petition and demand that the government invests in at least 90,000 social homes every year during this parliament.

[1] The net loss of social homes in the last year is calculated by comparing the 2018/19 number of social rent homes completed (6,287) with the 2018/19 number of social homes lost through sales (19,389) and demolitions (4,351). It is assumed that social housing sales and demolitions were previously let at social rent. This results in a net loss of 17,453 social homes.

[2] YouGov Survey on behalf of Shelter, 828 private renters in receipt of housing benefit, surveyed online between 12th August and 3rd September 2019. The figures refer to the last year.