Losing the plot: part 1

Published: by Alex McCallum

Last week saw the publication of the latest batch of results from the perhaps badly named Public Land for Housing programme (PLfH). Run by the Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG), the first programme started in 2011 with a target to sell land for 100,000 homes by 2015. This was followed by a further programme to sell land with room for another 160,000 homes between 2015 and 2020. These programmes are also targeted to deliver receipts of £5 billion (overseen by the Cabinet Office).

Can you spot the problem here? Well, the Public Accounts Committee commented in its 2019 report on public land sales certainly did: ‘There are potential tensions between the government’s two land disposals targets—for example, a sale of land that is suitable for new homes might not generate the highest proceeds.’

Two objectives for a programme; neither of which acknowledge the pressing need for affordable or social housing that we currently face in England today. Because of this, Shelter and others have long been critical of the programme’s design.

So, what has PLfH achieved to date? Well, fortunately we can now at least scrutinise the programme. Initially, MHCLG had been somewhat lax with their monitoring of the programme, so data had been absent for some time.

Progress so far

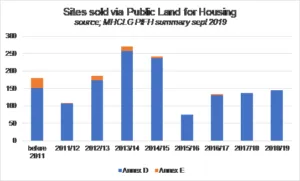

We start with the chart below, which is an annual breakdown of the number of plots that have been sold off under the programme.[1] The small orange segments show land that has been sold but where no planning or building data has been collected as yet.[2]

The first thing to note is the chart starts prior to 2011, when the programme actually began. And these plots represent 10% of all homes forecast from the programme. Were these sales motivated by the same aims as the current programme? This is another thing that the Public Accounts Committee have criticised; the inclusion of all sorts of public land disposals to try and hit the targets.

However, the biggest issue is the lack of progress being made in actually delivering homes. It really is surprising how few have actually been built.

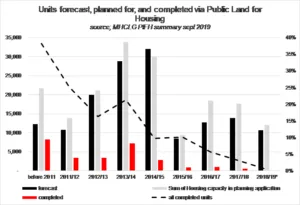

The chart shows the big problem – a system where selling off public land not only doesn’t lead to social housing, and doesn’t lead to much additional housing whatsoever. It presents the forecast number of homes (black); homes planned for in subsequent planning applications (grey); and the homes that have actually been built (red) on fully completed sites. The dotted line shows the percentage of planned homes that have been built.[4]

Over the decade that the programme has been running, only 15% of the planned homes – 27,611 homes – have been delivered on fully completed sites. If you include homes on land where building is still happening the results are a little better; 30% to be exact. And I’m sure I won’t be the only person disappointed by the length of time developers have taken to build homes; some things just don’t change.

And worst of all, only 1,410 units are expected to be some form of Affordable Housing; let alone the social rent homes we need more urgently. Less than one percent of all the homes delivered.

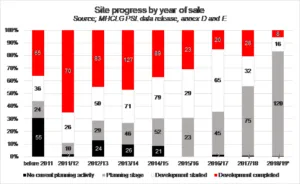

The trend in the chart above show more recent sales are likely to be in planning still, which is reasonable. It’s far less reasonable that 107 plots of land sold before the start of 2015/16 have not even reached the planning stage, that’s over 10,000 homes[5]. Of the sites sold before 2011, 64% are still to yet to fully complete construction; 44% have not even got through the planning stage.

Plans not plots

These results are entirely out of step with the government’s ambition to use public land to drive up housing supply. The inability of government to at least make sure former public land is promptly used for its intended purpose is particularly infuriating. Clearly something isn’t right with this programme.

The ambition to use public land sales to maximise sales receipts clashes with the ambition to maximise housing supply. The housing emergency is perpetuated by the inability of the private sector to deliver affordable homes – and maximising revenue on land in the short term is always going to make it harder to deliver the social and affordable homes we need.

Come back next week for part 2 of this blog, where we will explain how the government can make the most of public land for ending the housing emergency.

[1] There are a small number of sales that have not been recorded against a specific year (unusual, given that all sales should be recorded by the Land Registry), to avoid omitting these, they have been added to 2018/19 year – as indicated by the asterisk.

[2] Data from annex D has been tracked through the planning system, annex E data is sites yet to be tracked after sale. MHCLG have had to create a complex method to track sites because many have been incorporated into bigger projects.

[4] The data published has allowed us to analyse this by year of sale, for all tracked plots (so annex D only).

[5] 10,511 homes are forecast on sites yet to reach planning.