The benefit cap is undermining the government’s response to coronavirus (COVID-19)

Published: by Jenny Pennington

Ever since the government began to grapple with this public health emergency, one thing has been clear: the UK’s crumbling safety net of social security was going to have to be a corner stone of the response.

Despite Sunday’s announcement, if people can’t and shouldn’t go to work, they still need support to pay their rent and bills. And if they don’t get this, they will have no choice but to put their health and the health of others at risk, either flouting social distancing by going back to work when it is potentially not safe to do so or by trying to find a cheaper home.

The government has recognised this and responded to the effects of the coronavirus pandemic by pouring extra staff into processing benefit claims, lifting Universal Credit payments by £20 a week, and increasing housing benefit so it is now aligned with the lowest 30% of local rents. While this won’t be enough of a rise in housing benefit to fully support all those now in need of help, it’s been a huge effort that the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) should be rightly proud of.

However, there is another feature of the UK’s social security system that currently totally undermines this work: the benefit cap, which must be lifted for at least the next year for the new measures to have an impact.

The benefit cap means households aren’t seeing an increase in vital support

Our current benefit cap limits the maximum amount that an out of work household can receive, regardless of its size, to £20,000 a year outside of London and £23,000 inside the capital (a total that is slightly less for single people). Its purpose was intended to encourage people to find go into employment or move to a cheaper home – both things that the government are currently trying to stop people from having to do. Yet amazingly, the benefit cap is still in place.

Lifting both the Universal Credit standard allowance and housing benefit means that many households should see their overall entitlement increase, and we hope government will go further to help people pay their rents. However, some households will be taken over the benefit cap limit due to the increase, which means for many people the additional amounts will make no difference. DWP has lifted these benefits because it sees these additional payments as vital for all claimants to see themselves through the pandemic, but families will not be able to receive the full amount if the benefit cap stays in place.

This is a major issue for government. According to data released last week, even before the public health crisis, the benefit cap has already impacted 79,000 households in Great Britain.

This figure will have grown: demand for Universal Credit since the pandemic began has skyrocketed. A conservative estimate is that a third of private rented households (in addition to two thirds of social renting households) now rely on housing benefit to pay their rent. This growth shows no signs of stopping as we start to see the economic impact of the public health crisis.

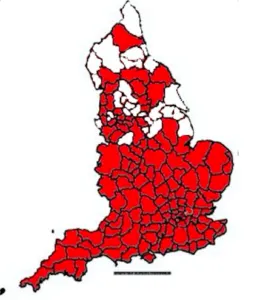

And it’s not just families living in expensive areas who have their benefits limited by the cap. The benefit cap is so low that even small families living in ‘affordable’ areas will lose out on the support they need and are entitled to. As the map below shows, a couple with two children in a typical two bed private rented home would have their benefits limited by the cap in more than one in eight areas of England. This includes areas not normally considered ‘expensive’ such as Luton, Northampton or Leeds. As the table also seen below shows, larger families could be liable throughout the country.

MAP: Areas in England where a couple with two children in a modest private rented home would have their income reduced by the benefit cap (areas in red)

TABLE: Proportion of areas where each family would be impacted by benefit cap (if not exempt)

| Single person | Couple | Single parent, one child | Single parent, two children | Single parent, three children | Single parent, four children | Couple, one child | Couple, two children | Couple, three children | Couple, four children |

| 18% | 0% | 12% | 47% | 76% | 89% | 32% | 82% | 100% | 100% |

Assuming family rents a home at the 30th percentile of local rents. Analysis carried out at BRMA level.

The benefit cap means that the government’s efforts are not getting to the families that need it, threatening their pandemic response.

Families are being left with little to survive on

The benefit cap also means that new claimants could go from relative stability into absolute destitution very quickly.

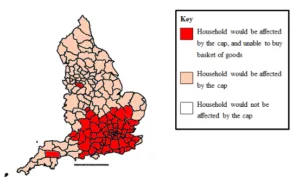

Receiving £20,000 or £23,000 a year might sound like a reasonable income, but the high cost of housing can mean it leaves families with very little left once rent is paid. To put these amounts in context, we compared them to the actual cost of living faced by families. The results are shocking: a capped one parent family with four children would not receive enough to cover the cost of essentials (such as rent, bills, food, toilet roll) in almost half (43%) of the country, causing extreme hardship and likely rent arrears.

If it is kept in place, the benefit cap will almost certainly increase the number of households made homeless as a result of the crisis, with knock on impacts on children, not to mention council finances.

MAP: Areas in England where a one-parent family with four children would be unable to afford essential costs

And it’s not just us who thinks this. On Thursday, we handed in a petition signed by over 140,000 people and backed by organisations working on the frontline of the crisis. The petition urges the chancellor to lift the benefit cap and to ensure that housing benefit covers average rents.

We urge the government to listen to these concerns and to make sure that people can stay safe in their homes by lifting the cap for the duration of the crisis.