Building a recovery on solid foundations

Published: by Alex McCallum

Today, Savills has published a report commissioned by Shelter on the impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) crisis on our struggling housing system.

The analysis is grimly familiar. The disruption of lockdown plus a hit on confidence will see supply and house prices falter and cause private developers to pull back from building while the storm passes. Because lots of social housing is delivered via developer contributions, we expect to see truly affordable housing supply fall too. If the worst happens, this year could see the lowest number social homes build since WWII.

So, when developers turn off the taps – causing potentially the loss of 218,000 homes in the next five years (or 318,000 in the worst-case scenario), and a 13% drop in social rent supply (23% in the worst-case scenario) – it’s likely to be small contractors that actually go without work. Savills forecast this could be as many as 171,000 jobs (or 244,000 in the worst-case scenario).

During this pandemic, the importance of our homes as a basis for our lives has been put into sharp focus – for work, for education, for our health – but new homes also have an important value to our economy too. Savills predict that the loss of supply in the next five years could result in a loss of £20.2 billion to the economy.[1]

We want to see the sector supported because another recession may again erode our ability to build the homes we need. Why?

- Experienced small contractors will go bust and may never return to the sector.

- Construction suppliers may also go bust, meaning materials become harder to source.

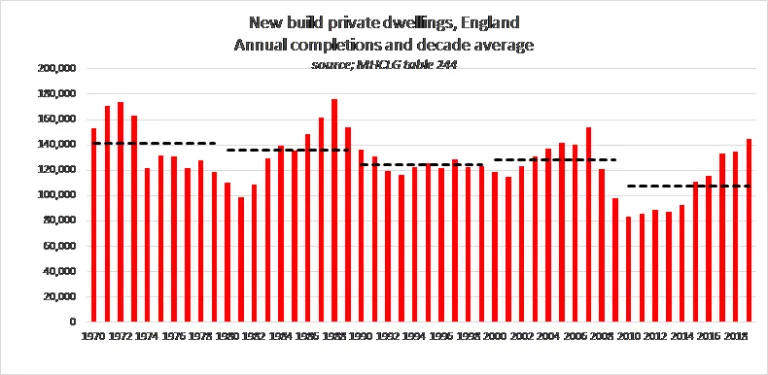

Market volatility is why productivity in residential construction is estimated to lag behind other UK sectors by 20%[2], and why private supply has slowly fallen ever since the 1970s; as the chart below shows.

Countercyclical spending

For years Shelter has drawn attention this problem, yet government already knows the solution.

Two words: countercyclical spending.

Here’s an example. When millions of people across the UK were threatened with unemployment because of the pandemic, the Chancellor decided to bail us all out with the Job Retention Scheme (furlough) a.k.a. countercyclical spending.

When someone receives unemployment benefits/ furlough payments they can continue to buy what they need. Had the Chancellor not acted, the businesses that were still needed – but had now moneyless customers – would have gone bust. And our economy would now be in a very dangerous place.

Unemployment benefit helps the individual first, but the same money goes on to help the local grocery shop owner, the local baker, the bank that provided a mortgage or loan; the list goes on. Government already uses countercyclical spending as an automatic stabilisers to keep the wheels turning. Sensible government investment avoids greater damage to the economy by providing a short-term lifeline. _And t_he same can work in construction too.__

Social housing is countercyclical

Publicly funded social housing is government’s countercyclical option in the housing market. In the same way as with furlough; as private demand falls and the risk of making a loss is too much for developers to bare, government knows it can step in and fund social housing instead, protecting jobs and providing the homes that are urgently needed.

- Social housing is a low risk investment, because rents are set by government not by a yo-yoing market. It’s a low risk investment in our future.

- Government can take advantage of its own low interest rates to borrow and fund building. Private developers don’t want to build, regardless of how cheap borrowing is right now.

- We have over a million households on the social housing waiting list. So, the homes they build won’t lie empty.

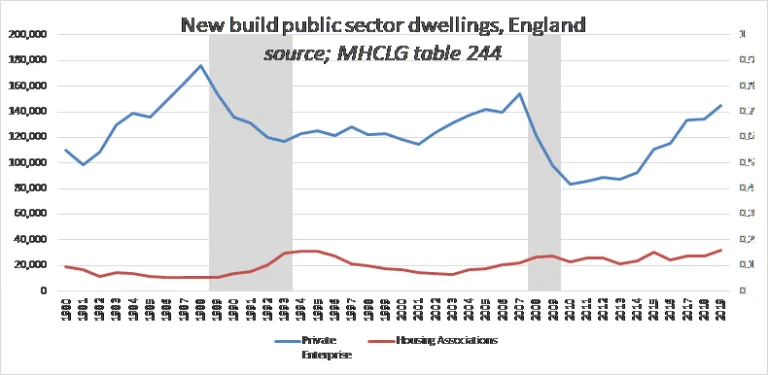

Again, governments of all colours know this but have never been ambitious enough; in 2008 the government bought homes intended for private sale and converted them to affordable tenures[3]. John Major did similar, when the Lawson Boom ended 1989.[4] This is clear to see below, with the recessions shaded grey.

This time we need to think big

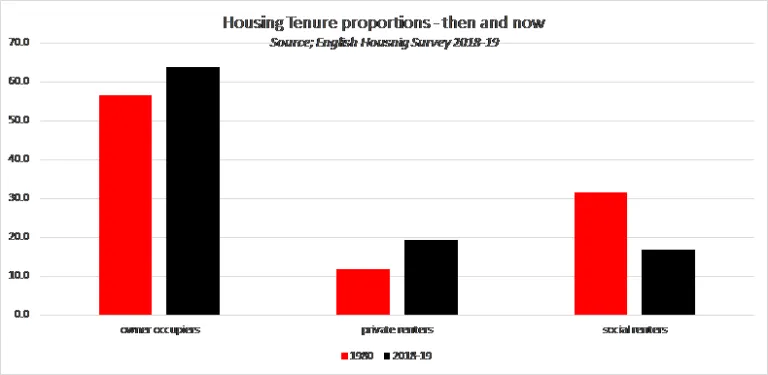

This time we shouldn’t make ‘perfect the enemy of good’. Government’s focus on ownership has meant policies that deliver quality housing are often rejected by governments seeking to get more people into overpriced private homes. Since the early 90s home ownership growth has faltered, despite ever more convoluted attempts at supporting the market to build costly private sale homes.[5] Responding to this crisis with homes that people can afford makes more sense.

We may have a marginally larger owner-occupier sector now (up 13 per cent since 1980), but we’ve also seen a 46 per cent drop in the social rented sector and a 62 per cent increase in the private rental sector – the most costly tenure in England – where most renters are not even able to save at all, let along save for a deposit.

By supporting residential construction through social housing investment, government can support the economy, help small building contractors and protect jobs. Shelter is calling on the government to:

- Accelerate the £12.2 billion Affordable Homes Programme, to make it a two-year rescue and recovery package;

- Spend the bulk on building new social rented homes with realistic grant rates and be flexible and imaginative about using grant; and

- Use the recovery as a launchpad towards delivering at least 90,000 social rented homes a year we need through a long-term programme.

This will also improve investment in skills and help improve productivity even when the market looks less profitable.

By taking this approach we can build a better future and deliver the safe, secure and truly affordable homes we all need.

Let’s build a better future: Sign our petition to demand the government build social housing

[1] The loss will be to Gross Value Added, this the contribution residential construction makes to the economy. The total loss of GVA results from the direct loss of construction activity, and the wider impact to the construction supply chain.

[2] https://www.housing.org.uk/globalassets/files/resource-files/supply/exploring-the-impact-of-long-term-funding-on-the-residential-construction-sector.pdf

[3] This was called Kickstart. Funding was made available to housing associations to buy private sale homes and convert them to affordable.

[5] Help to Buy, Starter Homes, Shared Ownership and now First Homes.