Renters at risk: Getting through the coronavirus crisis

Published: by Steph Kleynhans

With the end of the evictions ban this week, cases can now be heard again in the courts. And many private renters who might have felt secure in their homes before the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic now find themselves in a precarious position. Over 300,000 (3%) report that they’ve fallen behind on their rent, putting them at risk of eviction.

As lockdowns and restrictions become a more frequent way of life for us all, we cannot forget those who are disproportionately affected. The focus of recent weeks has been on getting ‘back to normal’. But for many private renters, ‘normal’ was stressful, unaffordable, and precarious. The ‘new normal’ needs to come with effective protections for renters.

We have published a new report highlighting the difficulties so many are facing as we head into winter, with the threat of further lockdowns and a weakening economy looming overhead.

Our findings

Our research lays bare the inadequacies in our private rented sector, and the holes in our welfare safety net that meant not everyone was caught – and sets out the changes needed to avert crisis.

The government took admirable action to cushion the blow to private renters by halting evictions, restoring the housing benefit rates for those in private rentals (Local Housing Allowance), introducing a Job Retention Scheme, and lifting the Universal Credit standard allowance – among other things. However, the last few months have seen unprecedented demand for Universal Credit. Four in ten private renters now receive help from the benefit system to pay their housing costs. And there were still many households who found that they missed out.

We’re calling for four main changes, to help protect renters now:

-

Create a Coronavirus Renters’ Relief Fund to help private renters pay off coronavirus-related rent arrears that put them at risk of losing their homes

-

Lift the benefit cap to ensure renters get the help they need to pay the rent going forward, and prevent a rising tide of homelessness

-

Align Local Housing Allowance (LHA) with the 30th percentile of local market rents (at the very least) – and urgently review to make sure that LHA is enough to cover the rents of all those who need it

-

Build much more social housing to create much-needed jobs and provide the genuinely affordable, secure homes we so desperately need

The benefit cap has prevented households from accessing the support they need

One of the most prevalent barriers to accessing this vital help is the benefit cap. Introduced to prevent those on benefits from receiving more than £20,000 per year outside of London, and £23,000 inside London has meant tens of thousands of households have been restricted from receiving the help they need – including the emergency measures the government introduced to help families stay afloat.

Households can be exempt from the benefit cap for nine months if they have been earning over £605 per month and in continuous employment for the previous year. But we have heard from many people who do not qualify for this grace period, leaving them totally exposed when they lose employment.

This is also suggested in the government’s statistics. We have seen a huge rise in the number of households being capped since the start of lockdown. As of February 2020, before lockdown, there were 79,000 households affected by the benefit cap in Great Britain. By May 2020, the number of households that had their benefits capped almost doubled. This means that more than 150,000 households do not benefit fully from the government’s emergency coronavirus measures. With the furlough scheme ending in October and the economic crisis set to worsen, many families will struggle to regain employment – and the effects of the cap will only worsen.

The impact of the benefit cap can be catastrophic. One person shared their terrible experience with the Work and Pensions select committee, explaining how the combination of losing work and being newly benefit capped had left them hundreds of pounds worse off:

I usually earn enough to remove the benefit cap, but because my work has shut down, my earnings have gone down and now I have been hit with the cap. I have now lost out on nearly £800 of money that would have covered all my bills and food shopping.

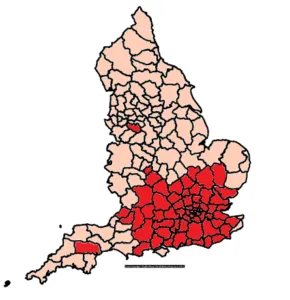

One of the possible options a family has to escape the cap is to move to a cheaper home. However, our research published today demonstrates that that is just not possible for so many families. Smaller families with just two children looking for a modest two-bedroom private rented home would have their benefit rate cut by the cap in more than eight in ten (82%) areas of England. This includes areas not normally considered ‘expensive’, such as Luton, Northampton or Leeds.

Map one: Areas in England where a couple with two children would be impacted by benefit cap (if not exempt)

The benefit cap is also causing destitution and poverty. Our new analysis shows that a couple with three children would not have enough money to cover essential items (food, bills, and personal care items) in close to half of England (43%). This makes it almost impossible for these families to avoid falling into rent arrears leaving them at risk of eviction and homelessness.

LHA rates are inadequate in the face of rising claimants****

LHA rates were restored at the very beginning of the lockdown, as they had fallen so far behind the market rents. They had been eroded through years of cuts and freezes so that they bore no resemblance to the 30% of each rental market they were meant to be covering. Ensuring that 30% of the market in each area became affordable to those claiming housing benefit at the start of lockdown was an important move, and one that will have prevented homelessness.

However, this was the level LHA should have been at before the pandemic. We knew housing benefit claimants were going to rise which would in turn require greater levels of market coverage. Our research shows that now nearly four in ten (39%) private rented households in the UK now claim housing support. This is up from three in ten before the pandemic hit. Clearly a system that covers the rent of just three in ten homes in each area is already inadequate. In areas particularly hit by lockdown restrictions (for example, an area with a high concentration of hospitality work) where there could be higher shares of housing benefit claimants in the private market, it may be even more difficult.

In these tough economic times and dismal employment market, households cannot also afford to make up shortfalls between their rent and LHA rate. We have seen the impact of rising shortfalls before the pandemic in the form of families being forced to cut back on food, sell their possessions or borrow money just to pay their rents. This in turn will lead to rising homelessness and we cannot let this happen again.

To prevent this from happening again and to help weather the oncoming storm, the government must urgently lift the benefit cap and make sure the LHA rates remain, at the very least, aligned with the 30th percentile of local market rents. The government must also consistently review LHA rates to ensure they cover enough of each local market in light of rising benefit claimants.

Financial support and building social housing

To help protect renters now, we need an emergency fund to help support tenants pay off unexpected rent arrears built up since the start of the pandemic in March. This would help tenants keep their homes and support landlords that rely on rental income for their livelihoods. You can help us achieve this by signing our petition now, calling on the government to do more for people facing urgent housing issues right now.

And of course, ultimately, the only way to provide people the stability to ride out hard times is to ensure that they have a safe, secure and affordable home to retreat to when they lose income. And the best way to do that is to build social housing, so that there is somewhere to go.