Behaviour change and welfare reform: If it’s working it’s hurting?

Published: by Kate Webb

Where will the axe fall? It’s the question that’s been preoccupying us here at Shelter, as we wait for confirmation of the government’s £12 billion planned cuts. We’ve been clear that we don’t think the safety net can sustain cuts on this level – and we don’t think they’re necessary. But it is clear DWP are scrutinising spending ahead of the Emergency Budget.

The Work and Pensions Secretary Iain Duncan Smith is said to favour cuts that incentivise behavioural change, presumably with the hope that people make choices or adapt their circumstances so that they need less support from the state. Reports over the weekend suggested the DWP was looking at capping child benefit, with the express intention to make people consider whether they could afford another child. Downing Street have been quick to reject the suggestion, because of a desire to protect the near universal Child Benefit.

But what of the underlying assumption that removing child benefit would influence big, personal decisions such as whether to have an extra child? Evidence is sketchy, which is not the best basis for sweeping reforms. It seems a stretch to imagine that the prospect of an additional £13.70 a week is really a carrot to encourage fertility. It’s probably fairer to say that the backstop protection of social security means an additional mouth to feed doesn’t cause the anxiety that it did before the Welfare State. Many would consider that to be a strength of the welfare system, not a problem to be overcome.

And what of the DWP’s record of encouraging behavioural change via the benefit system? There have been some notable flops. The £15 shopping-around incentive originally given to LHA tenants was confusing and didn’t achieve its objective of encouraging people to move to cheaper properties. In theory, the availability of in-work housing benefit should be a work incentive, but that’s been poorly understood in practice, even by advisers. And past studies suggest that factors like an individual’s work ethic or job prospects have a far greater influence on their tendency to look for work than the incentives or disincentives created by housing benefit.

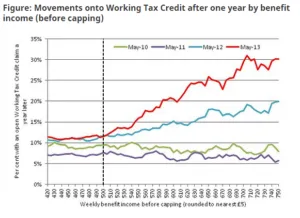

Ministers may be feeling more empowered of late, however. David Cameron has boasted that the overall benefit cap has caused a “stampede to the job centre”. That’s been disputed, but it can’t be claimed that the cap has had no impact on employment. The initial evaluation concluded that the policy had encouraged more work seeking activity, and the latest DWP statistics show that four in ten of those moving out of the cap have done so because they have found sufficient work to claim Working Tax Credits.

Source: IFS ‘Coping with the cap’ 2014, data taken from DWP evaluation.

Likewise the bedroom tax has had some impact on mobility within the social rented sector, which was one of the original objectives of the policy. In the initial evaluation, landlords estimated that 4.6 per cent of affected households had moved to a smaller home within the first five months. The evaluation noted “this seems high when compared to previous rates of downsizing” and predicted that 20 per cent of affected households would downsize within two years if this trend continues.

But such progress has arguably been achieved at a heavy price. The majority of households affected by the benefit cap have not moved into work and the IFS warns that we don’t really have a sense of how they are coping. Likewise the vast majority of people affected by the bedroom tax are having to pay a shortfall and are coping by cutting back on other spending, borrowing money or relying on Discretionary Housing Payments.

It’s also notable that both of these cuts have been very high profile and local authorities, housing associations, Shelter and others put enormous resources into warning people of the impacts and explaining what they could do to cope. This suggests that it’s not the subtle nudges of benefit regulations that influence people, but big signals and joined up thinking. This does raise the possibility that the same behaviour changes could have been achieved with fewer negative consequences. It should also caution us against assuming rules and incentives hidden in the intricacies of the benefit system will have similar effects. If the department are serious about generating behaviour change, it’s pretty alarming if the most effective method turns out to be bludgeoning cuts that are big enough to get noticed.

It’s right to look at what the benefit system incentivises or disincentives. Shelter and others welcomed Universal Credit precisely because it is intended to deal with some of the perceived work disincentives arising from housing benefit and its interaction with other benefits. The benefit system shouldn’t prevent or deter people from doing things that will make their lives better in the long run. That’s why it’s good that housing benefit supports mobility, allowing people to move to areas with plentiful jobs, even if rents are higher there. It’s also why it’s right to look at the rules concerning young people, to ensure people are supported to gain skills and qualifications and not shunted straight into dead end jobs.

But we shouldn’t overplay the extent to which the benefit system governs behaviour. People are not just “claimants” who may or may not make rational decisions in response to carefully drafted regulations; they’re human beings who interact with a host of agencies and systems and have a full range of preferences and motivations. Applying pressure to move to a cheaper area via housing benefit cuts will slam up against the wish to keep a child in the local outstanding school: people may choose to accept overcrowded or inadequate housing as the price.

The positive lessons of the last few years are that results can be achieved where agencies work together and prioritise actually supporting tenants to downsize or move into work, but that message is in danger of being lost amid the focus on big, blunt cuts.