Changes to homelessness law in Wales: Just Looking?

Published: by Shelter

Comparisons between England and Wales don’t end at Euro 2016. Wales have recently ushered in changes to their homelessness laws and practices, which differ significantly to England. The changes have been jumped on by commentators, politicians and the media, who see them as progressive steps towards resolving homelessness.

Our colleagues in Shelter Cymru (a separate charity) have broadly welcomed the reform. Now the changes have been flagged by a government inquiry into homelessness in England.

But what are the changes? Have they actually helped resolve homelessness? And could these changes also work in England? We took a look at what’s going on in Wales.

What’s changed?

The big change in Wales is the sharper focus on preventing homelessness as early as possible. Councils there now have a legal duty to prevent homelessness earlier on – starting from 56 days before someone loses their accommodation. This is regardless of whether the household are in priority need or not. Previously, the situation in Wales was as it is still in England: people are only considered to be threatened with homelessness if they are 28 days away from homelessness. And whether or not a council attempted to prevent that loss of a home is entirely up to them.

Welsh councils can now prevent homelessness in two main ways: either by helping a household to keep their current accommodation; or by finding new accommodation.

At the end of the 56 days, if a household is still homeless then the council still has a duty to re-house those who are in priority need and unintentionally homeless, as is the case in England.

It all sounds very straight forward. But it’s not, and there are some areas of the new legislation that we have real concerns about.

Is it working?

It’s too early to tell whether the Welsh approach is working, but initial stats reveal a mixed picture.

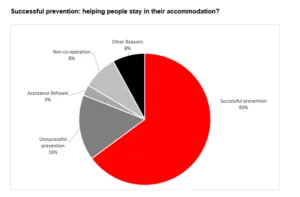

On the one hand, councils in Wales appear to be doing a good job of keeping people in their own homes – what the legislation terms ‘preventing homelessness’. The majority of households assisted under this duty were able to avoid homelessness.

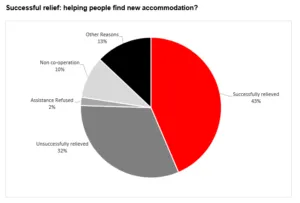

Councils have been less successful at helping people who are threatened with homeless find a new place to live – what the legislation calls ‘relieving homelessness’. This is not surprising, as it’s usually far harder to find new suitable, affordable accommodation than it is to keep people in their current homes.

Despite councils only needing to find someone a 6 month tenancy to count as ‘relieving homelessness’, welfare reform and rising rents in many parts of Wales are undermining council efforts. If this trend continues it will confirm our concern that the new laws are only as effective as the supply of affordable accommodation available to councils.

Despite councils only needing to find someone a 6 month tenancy to count as ‘relieving homelessness’, welfare reform and rising rents in many parts of Wales are undermining council efforts. If this trend continues it will confirm our concern that the new laws are only as effective as the supply of affordable accommodation available to councils.

What’s the catch?

So the results so far are mixed. But we have a number of other concerns with the Welsh approach.

Firstly, the Welsh model allows councils to meet their homelessness duty with a flimsy offer of a 6 month tenancy. This can either be in the private or social rented sector. In England, the minium is 12 months. We know from speaking to our clients that even 12 months is often not enough to give households the stability they need to get back on their feet after just experiencing homelessness. We hear all the time of people being made homeless again at the end of a 12 month tenancy – which feels like a revolving door of homelessness. We think anything less than a 12 month tenancy is simply unacceptable.

Councils also have a new power which allows them to terminate support for households that they believe are ‘failing to cooperate’ with the council’s efforts. We are worried that this power will be used in the wrong way. There is a clear risk of subjectivity when determining whether someone is ‘failing to cooperate’ with the council. There may also be reasons unknown to the housing officer which explain why the household is not engaging with them.

Finally, the Welsh model relies on local authorities being properly resourced to prevent homelessness. This new approach is more resource intensive than the old model – and councils in England have seen the funds they use to support homeless families reduced in recent years. At the same time, in many parts of England the housing challenges are far greater than in Wales, mainly thanks to an overheated private rented sector and a severe shortage of affordable housing options. We are concerned that in this context, extra burdens on councils will diminish the quality of support for all homeless housholds.

Can this work in England?

Despite its these shortcomings, we are very enthusiastic about the potential of the Welsh model. We support the stronger focus on preventing homelessness as early as possible, before people reach crisis point. Homelessness is not inevitable – it can and must be prevented. And this should apply to all homeless households, not just those in priority need.

And because the Welsh approach makes addressing homelessness a legal duty, councils are now more accountable for how they respond – it’s both more transparent and open to challenge. This is not the case currently in England and Scotland, and we know very little about what happens to homeless households helped through what is called ‘housing options’.

But ultimately, councils can’t prevent homelessness for good if people can’t remain in their homes, for whatever reason, or if there is a shortage of affordable housing to move people into. The challenge councils face housing homeless families is far greater in England than in Wales. Welfare reform bites deeper; rents are increasing across most of the country; and under-fire councils are seeing more and more homeless families each day.

So we need to be careful about receiving the Welsh approach as a nicely wrapped gift, ready to be instantly rolled out here. It will undoubtedly be a positive step in the right direction, but new homeless laws alone will not solve the housing crisis. If we are to see an end to homelessness we need to both fix the private rented sector and build the affordable homes that successive governments have failed to build.

Next up, we’ll be blogging about changes to homeless law and practice in Scotland.