DHP (Dysfunctional Housing Payments)

Published: by Shelter

When you’re on the brink of eviction, what do you think it takes to get your council’s attention? A lot, it transpires.

Discretionary housing payments (DHP) are the last chance saloon for families about to lose their home. Councils manage this pot of money, and are supposed to use it to help prevent people from becoming homeless, or in another type of housing emergency.

You may have fallen into rent arrears because of a housing benefit delay, or be hit by one of the myriad of welfare reforms – such as the bedroom tax. Never fear, is the government’s familiar retort, DHPs are here. It seems that they are the answer to every single housing problem out there.

But they’re clearly not, as our new evidence demonstrates

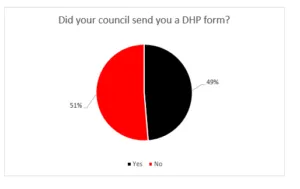

Our stats show that in many cases, requests for DHPs aren’t even being acknowledged. More than half of our clients facing homelessness, and who had tried to apply for a DHP through our online tool, didn’t even get sent a form by their council, or a way of applying for the fund.

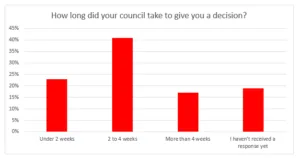

Those who do manage to apply for a DHP are more often than not kept waiting for at least 2 weeks. This may not sound like a long time, but it’s an eternity for a family who are watching the clock tick on the roof over their heads. What’s worse is that 17% of our clients had to wait over a month.

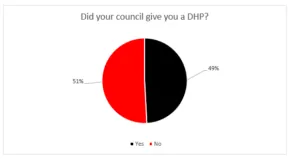

When people do get an answer from the council, it’s not always good news. Less than half of our clients were awarded DHP, despite facing hardship and imminent homelessness.

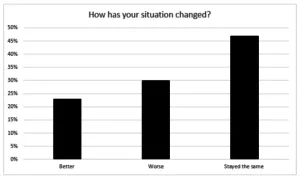

And what are the consequences of this? Almost half of our clients who needed DHP said that their situation stayed the same, which meant that in many cases they continued to inch towards eviction. But 30% said that their situation had worsened. Tragically, this often meant that families had lost their home and were now homeless. Despite support from Shelter, they join the 41,020 families who presented as homeless last year, and the thousands of other homeless households not captured in government stats.

So what’s going on? The overriding factor is that our safety net is broken and unable to protect people against increasingly unaffordable housing costs. Councils, are being asked to do the impossible in preventing households from being made homeless. In many parts of the country the gulf between rents and what families can afford to pay is too great for the limited pots of DHP to cover all cases.

Often this is because of welfare reforms, like the benefit cap and the bedroom tax. In fact the majority of DHP is spent by councils trying to soften the fallout of these two policies. Similarly, housing benefit in the private rented sector is now frozen, while rents continue to rise. By 2020 this will leave four-fifths of areas unaffordable to families who need help paying their rent in the private rented sector.

But this doesn’t excuse councils from failing to respond to inquiries and applications for DHP in the first place. We are particularly concerned with three specific areas of council practice:

Firstly, many councils actively stop residents from making inquiries in person or over the phone, and instead insist on digital contact only. This makes applying for things like DHP very difficult, especially when you’re in an urgent situation.

Secondly, DHP awards are often managed by outsourced benefits services. Communication with homelessness services often breaks down, and the council struggles to hold these external agencies to account. For families trying to apply for DHP, this can create a bewildering labyrinth of bureaucracy.

Thirdly, our findings on DHP reinforce evidence of councils actively ‘gatekeeping’, in other words trying to reduce the numbers approaching their homelessness services by deterring people from applying.

It is clear that councils must improve their practice in delivering DHPs. Despite the pressures they face, there are few excuses for not helping people to apply for support, at the very least.

More importantly, the government must take note of the impact that its welfare reforms are having on low income families and local councils. With more reforms due to go live over the next few years, and the insecurity that Universal Credit brings, DHP won’t be the answer to our dysfunctional housing system.