England’s cities: future home builders?

Published: by Pete Jefferys

As the dust settles on the election, it is clear that a major priority for George Osborne and David Cameron will be giving greater power to England’s cities. As the Chancellor said yesterday:

“We will hand power from the centre to cities to give you greater control over your local transport, housing, skills and healthcare. And we’ll give the levers you need to grow your local economy and make sure local people keep the rewards.”

This is an exciting, positive agenda and one which can clearly build on the greater autonomy that London has enjoyed over the last decade. It has been doubly re-enforced by the appointment of Greg Clark (the former Cities Minister) as the new Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government. Clearly there is momentum here, not just warm words.

But how should housing fit in?

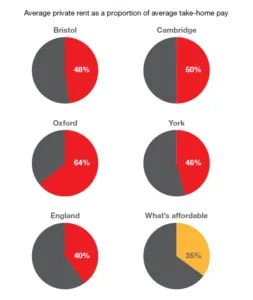

Cities are the engines of business creation, jobs growth and tax revenue but too often in England economic success is being matched with housing failure. Mid-sized English cities, places like Cambridge, Oxford, Bristol and York, are creating jobs but have terrible housing pressures that threaten to hold them back. It’s becoming impossible for young people to afford to move out and rent, let alone save and buy.

Rebalancing the national economy away from London to other cities will always be a challenge, but it becomes much harder when the places with the best job prospects cannot offer young working families a home of their own.

To combat this weakness, these cities need to be able to build many more homes quickly within attractive new communities. While they face some of the greatest housing challenges, they also offer the opportunity to pioneer a new approach.

In particular, growing cities need stronger tools in their armoury to get homes built. In other European countries like Germany and the Netherlands, strong, independent cities meet their own housing challenges by raising finance and using legal powers to buy land. In the Netherlands, cities buy land at low prices, put in infrastructure and sell it on to local builders who build the homes. They use some of the profit from rising land values to make infrastructure and affordable housing self-financing. There is much we can learn.

Fundamentally, we need to think more boldly about what cities can achieve when they have freedom over investment and powers to lead local development.

However, there are important questions to be resolved:

-

How can planning and investment for new homes be co-ordinated across council boundaries when political incentives are not aligned?

-

How can cities speed up house building on their brownfield land, when the current English house building market relies on slow, steady sales to maintain prices?

-

How can new development avoid local opposition? Evidence suggests that opposition is most inflamed by perceived pressure on local infrastructure and public services. The challenge is to build high quality new communities with new schools, jobs, health services and transport links that feel beneficial to the whole city.

-

How can a positive agenda for city green belts be developed? One which recognises and reflects public concern to protect beautiful places near our cities but also identifies ugly or low value land suitable for high-quality homes.

In a report out next month Shelter and the IPPR will be looking at some of the potential answers to these questions. With devolution a key priority for the government, it’s vital that our growing cities can build homes to complement their economic success.