English housebuilding heading for jobs downward spiral

Published: by Tarun Bhakta

We don’t yet have data for how many jobs have been lost from the housebuilding industry since lockdown began. But today’s labour market overview from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) has shown some serious early warning signs, with job vacancies in construction estimated to be down a huge 54% on the quarter.

We know that construction has been hit hard by lockdown, with output falling by 40% in April. We also know that there are weaknesses in the structure of the building sector, which in previous recessions have pushed it into a downward spiral of job losses.

The downward spiral of construction jobs

A decline in output in April was to be expected, as construction sites shut around the country to comply with new social distancing rules. But reopening sites won’t be enough to get the country building again.

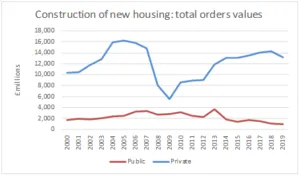

As we explained in a previous blog, an economic downturn and a resulting drop in house prices means developers stop building. Private housebuilding follows a boom and bust cycle. Right now, we’re looking at a bust.

As housebuilding drops, so too does the demand for construction workers’ labour and we see a decrease of jobs.

1. Big developers down tools

Big housebuilders know the housebuilding market has a propensity to boom and bust. This makes them reluctant to train and employ workers for the long term. Instead, a lot of contracting and subcontracting goes on.

Employment risk is pushed down the chain to small and medium-sized (SMEs) building firms, contractors, and subcontractors, who don’t have the same options open to them.

This in turn means big builders can down tools and close sites with ease. The incentives are skewed towards doing this. Developers can (and do) sit and wait for ‘another boom’ without having to worry about a big wage bill. In the short term, they can stop building and think about finding workers when the good times return.

But as we saw in the aftermath of the great financial crash of 2008, the construction industry might struggle to pick itself up again. The supply of new homes took a whole decade to recover.

2. SMEs exit or go under

Unable to sit on sites or shunt employment responsibilities down to smaller firms, SMEs are faced with some tough choices.

Without incoming demand for their housebuilding services, many SMEs exit the market – switching to another service, like repairs, or fold altogether.

In 2008, we lost one third of SME building firms. Not only does fewer SMEs mean a reduction in housebuilding capacity, it means fewer jobs, doing even more damage to the wider economy

3. Vacancies drop

For those that look to carry on building, the first thing they can do to survive when the work dries up is stop recruiting. Sharp drops in job vacancies shows firms trying to avoid getting to a stage where they need to make redundancies or fold altogether. They are a warning sign of things to come.

The 2008 financial crash saw a big drop in the availability of work in construction. And it took a long time to recover.

It’s too soon to tell what the size and shape of the drop will be this time round. Official employment numbers have not yet shown a big decline. We may not see it materialise for several months. But according to ONS figures released today, vacancies in construction were down 54% on the quarter between March and May, and down to their lowest level since 2013. So, there is strong evidence firms are stopping recruiting. Jobs are at risk.

4. Construction workers leave the industry for good

Construction is characterised by unusually high levels of self-employment. Between January and March, self-employed workers made up 40% of the total construction workforce, as opposed to under 20% across all industries.

Faced with a lack of work, many of these workers have no choice but to up sticks and train in another profession. As the Construction Skills Network forecasts show, the main outflow of workers from the sector is transfer to other industries. This means the workforce may no longer be there to start building again when the market picks up again.

It also has an ageing workforce. According to the Construction Industry Training Board, a disproportionately high proportion of over 50s leave construction before retirement age in ordinary times. A drop in demand for construction services risks many more taking the decision to retire early.

With few new recruits coming through and apprenticeships also likely impacted by the pandemic, all these workers leaving means a permanent loss of skills in the construction industry. The end of the transition period as Britain prepares to leave the EU will only add more pressure and uncertainty.

Averting the spiral

England’s housebuilding sector has got hooked on the boom bust cycle of building homes for market sale. It needs proper reform to make it more resilient and diverse. Social housing can provide immediate help to avert the jobs spiral and it can help us build a tougher, better industry.

Government spending on housebuilding can continue through a downturn. Unlike market sale homes, demand for social rent is also resilient. This provides the certainty and stability that the construction industry needs to keep employing.

Shelter will continue to campaign to ensure that renters, rough sleepers and households stuck in temporary accommodation are able to stay safe as long as the pandemic continues. But we are keeping one eye on the future too.

With a recession looming and a drop in private housebuilding inevitable, the government must act to protect jobs in the construction industry. It must build social housing now.

Please sign our petition urging politicians to prioritise social housing and build the homes we so urgently need.