Help to Buy is not the answer to building enough homes

Published: by Shelter

Help to Buy is this government’s biggest intervention to date in the housing market and ministers often portray it as a major part of their answer to the housing shortage. However our analysis shows that this approach cannot deliver enough homes to meet need. The only way it could is if the average price of a home in England reached an astonishing and implausible £9 million.

Let me explain.

The current – and orthodox – thinking is that the supply of new houses relies upon being able to sell the houses and that these sales, in turn, require mortgages. The government feels this chain of events is efficient and thinks that helping boost mortgages via the Help to Buy schemes will allow further sales and so new houses will be built. This approach may at first glance feel intuitively correct but it has problems: 1. increasing peoples’ bidding power by allowing potential owners higher loan-to-value mortgages will lead to increases in prices because the number of homes doesn’t change very quickly and; 2. the supply of new housing does not respond quickly or efficiently to price changes (and therefore more demand).

While this approach may be more useful in the short term as a quick hit to the market it is a flawed approach for the large housing crisis we face.

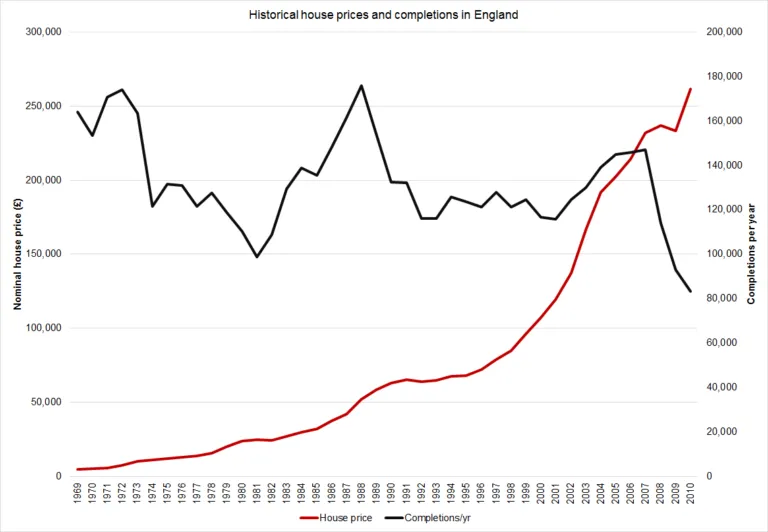

First of all, the historical link between house prices and new housing supply is incredibly weak – at best, supply is extremely unresponsive. In a functional market, you would expect more new houses to be built when prices go up and fewer new houses when prices go down. As we can see below though, the number of new houses built by the private sector has fallen, even as house prices boomed.

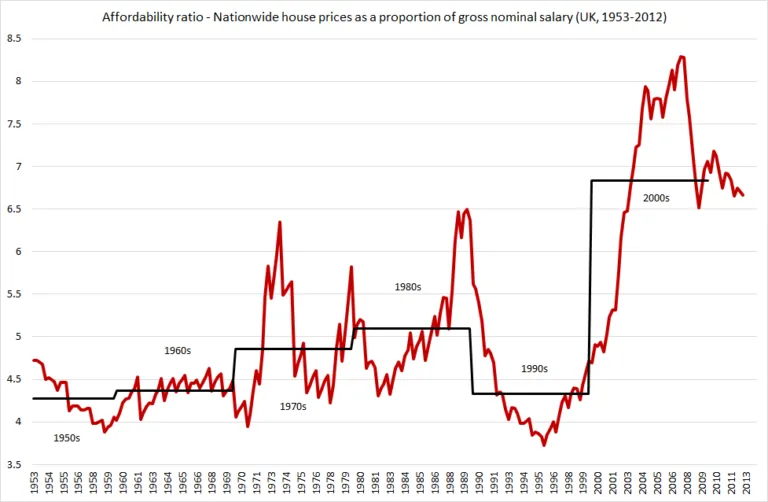

In fact, looking at the private building market over the last 50 years it seems that each time there is a recession it takes an even more massive house price ‘hit’ – particularly compared to earnings – to get the builders growing again. The increase in supply between 1981 and 1987 coincided with house prices increasing from 4.5 times to 6.5 times average salary while the supply ‘boom’ from 2001 to 2007 needed an increase in house prices from just under five times to over eight times average salary.

When developers do start increasing output again, it never recovers to its previous peak before the next crash. Understandably, given how volatile and dysfunctional the market is, developers are only acting in a rational way to ensure the business model will work. However, as Help to Buy only supports this model, this toxic chain of events can’t be broken.

Let’s look at the most recent – and unsustainable – housing market boom. Between 2001 and 2007, house prices leapt over 93% from around £120,000 to £232,000**.** Over that same period, housing completions per year in England increased by only 27% from around 116,000 to 147,000. This recent history shows how house prices and new supply have become disconnected. But it also shows that the private sector has not been able to build the 250,000 new homes per year we need to satisfy demand, even in the boom years.

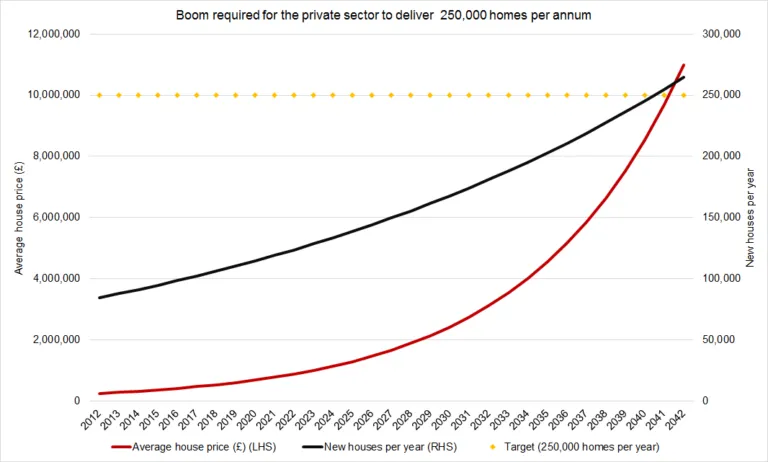

House building is now finally picking up again (in terms of annual starts) albeit from a low base and partly thanks to Help to Buy. However, if this recovery were to follow the pattern of the last one (2001-2007) in terms of housing completions and house prices it would take three decades for the market to reach 250,000 new homes in a year in England, and only then if house prices kept rising throughout. By the end of that boom period the average price of a house in England would have to have risen to £9 million to sustain the growth in building.

Of course, in reality this could never happen: a boom would never be able to last this long. Almost everyone would be priced out of the market long before it reaches this point; developers would struggle to sell the homes, and the market would go through another down turn of the cycle. But this illustration does show how dysfunctional the current housing market system is, and how badly reform is needed.

Of course, in reality this could never happen: a boom would never be able to last this long. Almost everyone would be priced out of the market long before it reaches this point; developers would struggle to sell the homes, and the market would go through another down turn of the cycle. But this illustration does show how dysfunctional the current housing market system is, and how badly reform is needed.

What we need is reform that breaks this cycle of booming house prices and tepid or falling house building. We need to look at the land market and how to make more land available for building at lower prices. We need to make the house building industry more diverse and competitive and we need to boost building by not-for-profit providers and local authorities by investing in affordable housing.

Relying on a house price boom to solve the housing shortage sounds dangerous. It is. And it’s also a strategy that history suggests simply won’t work.