Homelessness: Strategic prevention is better than crisis-driven cure

Published: by Deborah Garvie

With growing numbers asking their councils for help to find somewhere to live, there is an increasing debate on how we prevent homelessness. As we enter a period of further economic uncertainty, we must remain alert to the risk of greater levels of homelessness.

So, we’ve published a new briefing on preventing homelessness to contribute to this debate.

On the face of it, preventing homelessness is pretty straightforward – provide more homes. Not just expensive ‘starter homes’ for those lucky enough to be able to afford to buy. But, for people who struggle to compete in the market, low rent homes let by councils and housing associations where they are most needed, plus adequate assistance with private rents and other costs, such as tenancy deposits.

Any serious national or local government approach to prevent homelessness must seek to address availability and access to rented homes for those who can’t afford to buy.

However, some people will be at far greater risk of homelessness than others: those who are socially excluded and face prejudice in the private rental market, such as benefit claimants; single parents who can only rely on one income to pay for a family home; and others whose incomes are too low to afford local market rents.

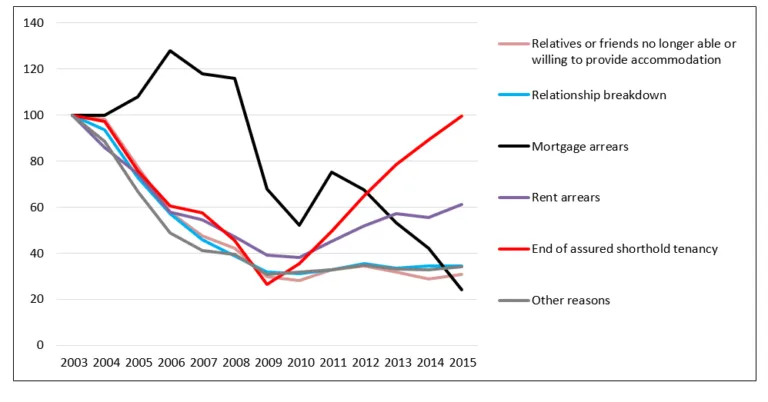

Of course, people can also lose their homes because of personal factors, such as relationship breakdown with a partner or parents, or lack of support when they are struggling to manage their affairs, perhaps as a result of illness or disability.

But national statistics show that recent growth in homelessness is primarily due to the instability and unaffordability of private renting: structural housing pressures mean more people need help with affordability problems.

The change in the number of households made homeless due to different triggers since the Housing Options model was introduced (Index 2003=100):

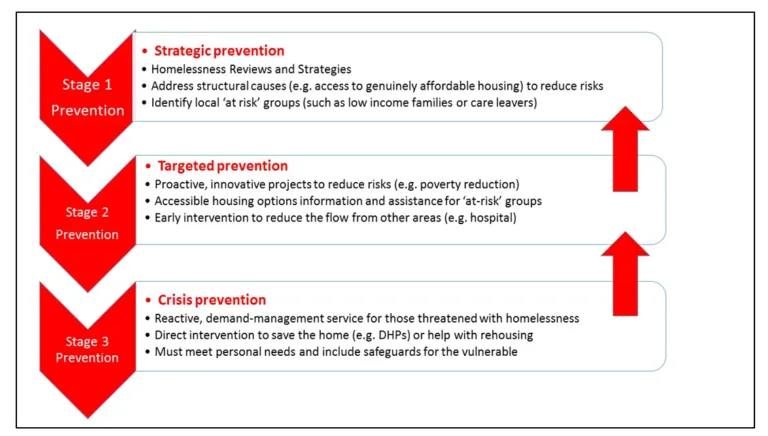

For the past 10 or 15 years, councils have been encouraged to take a more preventative approach to homelessness, by assessing the main causes of homelessness in their areas, developing strategies to address them, and by targeting pre-crisis intervention at those most at risk, via provision of ‘housing options’ advice and assistance.

For the past 10 or 15 years, councils have been encouraged to take a more preventative approach to homelessness, by assessing the main causes of homelessness in their areas, developing strategies to address them, and by targeting pre-crisis intervention at those most at risk, via provision of ‘housing options’ advice and assistance.

However, in reality, such advice is only offered when people approach at crisis-point, already threatened with homelessness, which is where the homelessness legislation is designed to apply. This has led to an uneasy tension between law and practice, and ‘gatekeeping’ of statutory rehousing assistance, which is designed to protect families and other vulnerable households in a crisis.

In our view, ‘housing options’ advice should be proactively targeted at people at risk of homelessness much sooner to avoid them becoming threatened with homelessness. This should be regardless of whether they might be entitled to statutory assistance. It should support, and not replace, statutory rehousing help for vulnerable people.

We need to see a shift to much early intervention to prevent homelessness, to move us away from a crisis-driven approach. As our briefing shows, where local authorities and advice agencies do invest in early intervention the results can be impressive and there are lots of examples of good practice that can be built on.

Examples like Breathing Space in Wakefield, which deals with mortgage arrears before they threaten families with homelessness, or the Leicestershire Housing Enablement Service, where the NHS and councils work in partnership to ensure that the threat of homelessness doesn’t delay hospital discharge. At Shelter, we’re continuously looking for ways to ensure people can get the information and advice they need long before they’re threatened with homelessness, via our Get Advice pages, Helpline and local face-to-face services. In response to requests, we’ve recently piloted advice via social media.

We must, of course, consider the potential for changes to legislation to provide increased support to homeless people. However, in the meantime, there is already a great deal that the Government can do to support and champion targeted intervention, while also tackling wider structural problems of housing insecurity and unaffordability.

Homelessness is not inevitable. It can and should be prevented. There’s no time to waste.