How do we grow our successful cities?

Published: by Pete Jefferys

1,590 new jobs, just 146 new homes.

That’s been the average for Oxford each year since the 2007/08 recession. It’s a similar story in Bristol, Cambridge and York – together the four ‘Growing Cities’ that we looked at in our new report with the IPPR.

They are all examples of successful city-economies which are internationally competitive, creating jobs in tech, medicine, advanced manufacturing and professional services. But they also have dismal records for house building compared to what they need.

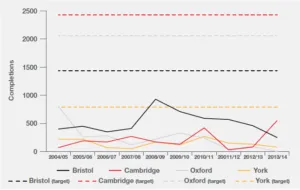

Affordable housing in the ‘Growing Cities’: need versus completions

A failure to build enough new homes has obvious social implications: more young families are priced out of an affordable, stable home, and pressure on already high rents mounts. And it also impacts on cities’ economic success – such that business leaders are increasingly concerned about the cost of housing. Unless England’s mid-sized cities can offer their workforces decent homes at reasonable costs, their firms will struggle to attract staff, undermining their ability to compete and grow.

So what’s gone wrong?

Our new report focuses on four issues, each of which should be addressed head-on as part of the current debate about devolution to England’s cities. Only by putting housing at the centre of the devolution debate can we make sure that our Growing Cities can remain competitive, affordable and liveable.

First, boundaries. We need to overcome the limits to growth created by the outdated, artificial boundaries that carve up our successful city-economies. There are deep political waters here, as boundary changes are always controversial. Our approach is to provide much stronger incentives for cities and their neighbouring authorities to do the right thing and co-operate constructively, rather than impose new structures from Whitehall. The City Deal process must push this harder, and reward city-regions which set up new Joint Strategic Planning Authorities. Among the cities we looked at Cambridge is the leader in this field, having spent decades building up productive planning relationships with the surrounding area.

Cities where local councils co-operate fully in planning across boundaries should be rewarded with stronger powers, devolved funding streams and the ability to combine resources. Those which consistently refuse to co-operate should be locked out of growth funds and face the ultimate threat of a fast-tracked boundary review if no deal is ever reached.

Second, brownfield land. After two decades of ‘brownfield first’ policies, our Growing Cities told us they have limited brownfield land left available. However there is strong political will to leave no stone unturned. In practical terms though, the cities are too often powerless to get stalled brownfield sites moving. The old Sorting Office in Bristol is a clear example. It has been derelict for 17 years, despite being ideally located next to the main train station. Finally this year the council managed to acquire the land from its owner (a private equity fund) but the process is too slow and too difficult. This means that land speculators have little incentive to develop where they have their own reasons for leaving sites derelict.

We argue that cities should be given new tax powers that could impose a higher holding cost on land identified for growth, to shift the balance of incentives firmly in favour of development. More importantly, compulsory purchase should be made much easier, to provide a hard incentive to get sites moving.

Bristol brownfield, stalled for 17 years – finally being redeveloped

Third, large sites. Our cities have an awful record of planning and delivering large sites compared to other European countries, whether in new settlements, brownfield regeneration or urban extensions. Even the best examples from England compare poorly. Bicester ‘eco-town’ near Oxford is being built 10 times slower than the comparable Kronsberg development near Hanover, Germany. The crux of this problem is the way the land market works here. We have a land market which actively discourages high quality or quick building, by forcing developers to compete, not on quality or price, but on who can fit the most small boxes onto the smallest piece of land and then drip feed their sales to maintain high prices. A better approach would involve Dutch-style ‘active land’ policies, to bring land in for development at lower prices. This would also help create opportunities for local builders, community groups and self-builders.

Fourth, green belts. The debate around this huge chunk of land (which has doubled in size since the 1970s) is increasingly polarised between those who want to effectively scrap them and those who want to preserve them in aspic. Neither approach will wash for long, as developers continue to nibble away through legal appeals. Equally the current debate too often fails to recognise that many parts of local greenbelts are not loved by local people – the brownfield sites or mono-crop fields without public access.

Not all greenbelt is green: land north of London with greenbelt status

We advocating creating Green Belt Community Trusts, which would allow communities to protect the most valued parts of their green belts with Country Park designation, and let planning authorities identify the least valued parts which can be put into a Community Trust. Like the Letchworth Garden City’s Heritage Trust, holding land in perpetuity like this could ensure any future development is affordable, sympathetic and comes with good quality infrastructure for local people. Like Letchworth, it would do this by capturing the land value created by releasing green belt – which would run into the billions for even small amounts of green belt land. For example, using just 5% of the Oxford or Cambridge green belts could release £1.4bn of value.

Overall, this plan aims to give cities the tools they need to tackle their own housing shortages. Central government can’t do everything and, as we’ve seen over recent decades, neither can the market alone. The new government’s commitment to the city devolution high agenda represents a fantastic opportunity to get affordable homes built, improve residents’ quality of life, and support the economies of our growing cities.