If it is broke, it needs fixing

Published: by Alex McCallum

Today sees the publication of the Children’s Commissioners’ report, Bleak House. It’s an upsetting exploration of the awful conditions that homeless families are having to endure, and highlights how broken our housing system truly is.

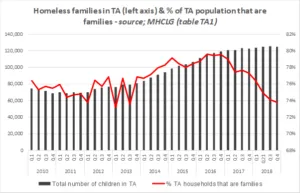

The report shows that temporary accommodation (TA) is rarely that at all; 40% of families stay in TA for over 6 months and 5% – that’s one in 20 families – end up in temporary accommodation continuously for a year or more. These are not trivial numbers. There are 62,000 homeless families in temporary accommodation right now – that’s over 124,000 children without a home.

And this is just the visible tip of the iceberg; other families overcrowd or sofa-surf because temporary accommodation is, unsurprisingly, not an offer they want to take up. Would you? The report describes cramped accommodation where families might have to share facilities (if there are facilities at all), alongside vulnerable adults, perhaps with mental health or substance abuse problems.

Sadly, this is not a new problem. The number of homeless households have been increasing for years; families in temporary accommodation have nearly doubled since 2010. In total, the Children’s Commission estimate that the number of homeless children in England is likely to be over 210,000, with a further 375,000 at risk of becoming homeless because they are falling behind with their rents or mortgage payments. That’s well over half a million children homeless or at risk of losing their home.

No choice

This point might feel self-evident, but families who accept the offer of temporary accommodation are desperate, they have no other option. We know the cost of housing is now extremely high, with house prices so high that ownership is out of reach for most people; meanwhile private renting is unaffordable too, with the average renter paying 41%[1] of their take home pay (including benefits) on rents. These families need social homes with rents pegged to local incomes to make sure they are truly affordable.

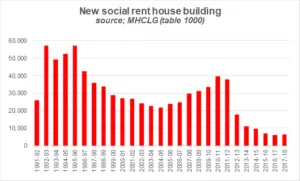

But in the last 5 years, the average number of social homes built has been a lowly 7,900. Despite the clear and persistent need, successive governments have been reducing the level of funding for the kind of housing – social housing – that these families really need.

The solution

The report makes important recommendations which Shelter can wholeheartedly support; Why? Well, because the solutions are abundantly clear if you care to review the evidence.

Volume housebuilders can never build so many private homes that prices go down – they aim for the ‘market absorption rate’. We can’t expect them to hit the target of 300,000 additional homes set by government. And of course, many commentators wonder if more supply can ever impact on prices. Following decades of policies to pump up house prices, we are now stuck with private housing that is fundamentally unaffordable to most households and particularly low-income families. Private housing need not be the only solution.

By building social housing, government can guarantee that new homes will be affordable to struggling families, can make sure these homes go to those who need them most, and doesn’t require volume housebuilders getting around to building them: government can support councils and housing associations to build them.

In short, and as we suggested in ‘A vision for social housing’, our Social Housing Commission report published this year, government needs to take real ownership of the housing crisis and actually fix it. We need more social homes, so homeless children don’t have to spend long periods in temporary accommodation. We need government to commit to investing in new social housing in much higher quantities, starting immediately. While we’re building these homes, Local Housing Allowance payments need to increase so they actually pay the high rents that private landlords charge.

[1] English Housing Survey 2017-18; Household Representative Person and Partner net incomes and benefits.