In praise of Community Land Trusts

Published: by John Bibby

There are definitely cases when the most efficient way to expand the supply of a uniform product is to back existing large producers and to offer them incentives to supply more. You would imagine that it was the case with car production or pharmaceutical manufacturing, for example.

Not so with housing in England.

England’s big builders are bigger than ever before and responsible for a greater share of house building than ever before. And England’s rates of private house building are the absolute pits.

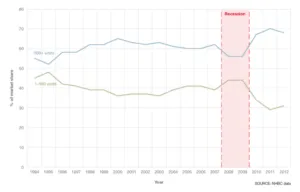

It’s easy to forget that the number of homes built by the private sector in the last few years is lower than at any time since the early 1950s. The number built last year (93,660) is lower than in any of the fifty-odd years between 1955 and 2009. Levels of private building in 2014 were lower than at the very bottom of the trough of the house price crash in the early 1990s; lower than during the early ‘80s recession; and lower than any point during the mid-70s recession, energy crises and three-day week.

This is despite the highest house prices (i.e. theoretically the largest supplier incentives) that the country has ever seen.

But the increasingly dominant big developers have not turned their market position into a considerably increased output of new homes. In fact, they are unlikely to be able or willing to sufficiently expand the number of homes that they build every year – no matter what gets chucked at them. Unable: because they just don’t seem able to take advantage of economies of scale. And unwilling: because they’re business model isn’t designed to maximise the number of homes they build, but “deliver new homes as fast as they can sell them”.

So unlike producing a lot of cars or manufacturing a lot of pharmaceuticals in a hurry, when it comes to housing, having a small number of big suppliers is a part of the problem.

This is why Shelter has been arguing for a more diverse group of private builders and developers – and one that includes many more small-time producers with different funding and development models to the big players.

An interesting example of these new producers are Community Land Trusts, which are beginning to gain some serious traction and deliver homes.

Community Land Trusts (or CLTs) are not-for-profit organisations that develop housing and are run by the local community for the community’s benefit. They can be charities or registered providers or companies, but membership must be open people who live locally .and members must then control the trust.

On the face of it, they sound like a tough sell to traditionally-minded policy makers. They are small scale. There are a lot of them. And they suggest the risk of working with real people rather than industry types. But many of the same things that make them sound difficult are the qualities that can help them to deliver new homes in a place or in a way that a large developer never would.

The fact that they are rooted in the local community means that they are absolutely committed to that community. The importance of this point can’t be overstated. If the numbers don’t work in a particular location for a profit-motivated developer then it will just move onto somewhere where they do. Or they will just try to whittle away at the amount of affordable housing to be delivered on the site, even if that means local people can’t afford to live there. Public sector organisations can have other priorities and ‘bigger fish to fry’ or just see particular sites as being too difficult, particularly when it comes to the need for small numbers of new homes in rural areas.

CLTs, on the other hand, are defined by the community that they serve and this can drive them to go to extraordinary lengths to make developments work in areas that others would have written off. Just look at the story of the East London CLT’s pursuit of a site.

And because they are able to get the community onside it also means that they are more likely to be able to build the consensus needed for new homes. It’s hard to object to a development when you or your neighbour or friend has played a part in its creation – or at least when you’ve all had the opportunity to do so. What’s more, the fact that CLTs continue to be run by the community for its benefit even when the development is complete means that the existing community is getting something back for supporting new homes. Recognising this power, East Cambridgeshire District Council has, for example, decided to deliver all its affordable homes through CLTs.

The National Network of CLTs recently published its pre-election pitch to support the growth of CLTs in England over the next parliament. That growth is not ‘the answer’ to England’s housing shortage and we will need our existing large developers firing on all cylinders if we are to build the 250,000 homes a year that we need. But as Shelter has said numerously, the idea that there is a single answer is a simplistic misconception. And it’s likely the same simplistic misconception that might lead you to try to solve the housing shortage with the smallest number of large developers as possible.