Land banking: what’s the story? (part 2)

Published: by Pete Jefferys

As we saw in the first part of this blog, land banking is a normal part of development but it’s not a simple story. The big developers certainly own and control a huge amount of land which could be used for housing. There are also land trading companies that don’t build homes but land bank purely to cream off profits. However, the housebuilders are right to say that to a large extent they need to hold a future pipeline of land in order to run their businesses.

But the focus on land banks misses the more important question entirely. Why are speculative developers failing to build homes that people can genuinely afford in sufficient numbers? Land banks are a symptom not a cause of our dysfunction housebuilding system.

Speculative housebuilding

The main business model that developers use in England is a speculative one. This simply means that developers are usually building for an unknown, potential future buyer, rather than a confirmed buyer in the present. It is therefore a risky business. There’s the risk that the housing market might turn because of an external factor (for example, Prime London developments at the moment). There’s also the risk that the site you buy will have complications which add extra costs to the construction. And there’s always a risk that you won’t get the planning permission you want. This means that the role of the main housebuilding ingredient – land – is absolutely critical.

Speculative developers buy land in competition with one another. One of the factors they must compete on is the final selling price for the homes they build. They determine these prices by looking at the local second hand sales market – in particular the volume of transactions and the range of sales prices (per square foot).

What these competing developers are trying to determine is how quickly they can sell homes in this area for the optimum price. They need to know this, because if they assume sales prices which are too low then they might offer too little for the land and be outbid by someone else. Conversely, if they offer too much for land because they presume too high sales prices they might not make a return. The rate at which developers build (and more importantly sell) is therefore determined by the optimum prices that can be achieved, given the local second hand sales market.

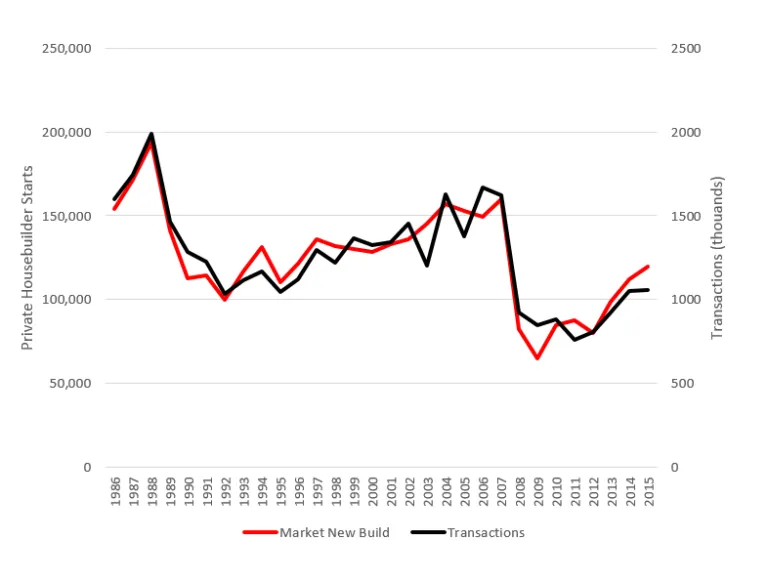

This is why the overall level of house building rises and falls consistently with overall sales (see graph below). It is also why recent analysis of housebuilding sites by NLP found that large sites build proportionately much slower than medium sites – all sites are being built as fast as they can be sold for the optimum price.

Overall market transactions and market new builds

This creates a dilemma

At the moment, transactions in England’s housing market are falling while house price inflation is lukewarm. This is due to a combination of mostly demand-side factors such as affordability thresholds, Stamp Duty changes and broader economic uncertainty. Changing one of those factors (such as cutting the extra stamp duty) might increase transactions, and therefore market building, but it will also feed into higher prices. This is because it will mean attracting more buyers willing and able to compete to buy homes at higher prices.

This creates a dilemma at the heart of speculative housebuilding – and something not evident yet in housing policy. The received wisdom is that to limit house price growth we need to build more homes. But the only way to sustainably increase the number of homes built under the speculative model alone is to increase transactions in the second hand market. But increasing transactions in the second hand market means increasing demand and therefore inflating prices. And prices are precisely the problem we are trying to solve…

It’s hard to see how you could build your way out of England’s house price problem with speculative housebuilding alone. Speculative housebuilding reacts to the wider housing market; it doesn’t lead it.

Those on the political left who blame land banking for this situation would be missing the point, as the size of land banks does not determine the pace of building. And those on the political right who blame a lack of planning permissions are missing just as big a point – England consistently grants twice as many permissions as homes are started. Ultimately, neither of these factors determines the level of market housebuilding.

So what do we need?

The only way that we will sustainably increase house building to a much higher level, without simultaneously adding to demand and pushing up prices, is if we add increase supply outside of the speculative housebuilding model. We need the speculative housebuilders to do their bit, but we cannot expect them to do it alone; in fact, it runs entirely counter to their business model.

In the coming months we’ll be looking at how this might happen through what we will be calling “New Civic” housebuilding. This will draw together the lessons of the very high quality, attractive and affordable developments which were common in England’s past, and remain so in other countries, but are sadly too rare in England today. The New Civic housebuilding movement we can see emerging offers the real hope that we can double housebuilding by creating popular, locally affordable and high quality new developments.